Orthotic devices for hallux limitus are designed to limit first metatarsophalangeal joint motion while providing cushioning and plantar pressure distribution. A lack of quality research on conservative treatment of the disorder, however, forces clinicians to rely on their own experience.

Orthotic devices for hallux limitus are designed to limit first metatarsophalangeal joint motion while providing cushioning and plantar pressure distribution. A lack of quality research on conservative treatment of the disorder, however, forces clinicians to rely on their own experience.

By Hank Black

Hallux limitus is a painful, degenerative condition of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint characterized by restricted range of motion (ROM) at the great toe and progressive osteophyte formation. This restriction of the first ray is believed in most cases to be caused by trauma or multiple microtraumas that cause damage directly to the articular cartilage and restrict the windlass mechanism from functioning smoothly.1

Hallux limitus is the second most common condition of the first ray, after hallux valgus.2 Two-thirds of hallux limitus patients have a family history of the disorder, and up to 79% have bilateral effects.3

Although there are several descriptions of functional hallux limitus, Laird defined it first as nonweightbearing dorsiflexion of greater than 50°, with less than 14° of dorsiflexion at terminal stance.4 Patients typically present with pain and stiffness at the first MTP joint, plantar calluses, and enlargement of the joint.5 In some patients, however, pain does not correlate with advancement of mechanical restriction of the joint even with radiologically confirmed joint space deterioration.6

Functional hallux limitus becomes structural hallux limitus as the stress of repetitive loading in gait makes the first MTP joint susceptible to developing osteoarthritis (OA).7 The end-point of hallux limitus is near-total restriction of movement, which is called hallux rigidus.8

However, functional loss of hallux dorsiflexion at the first MTP joint may occur even when adequate dorsiflexion is available in a nonweightbearing condition.9 And some patients will have a functional restriction and pain only on weightbearing, but no appreciable structural changes.8

However, functional loss of hallux dorsiflexion at the first MTP joint may occur even when adequate dorsiflexion is available in a nonweightbearing condition.9 And some patients will have a functional restriction and pain only on weightbearing, but no appreciable structural changes.8

Identified risk factors include an abnormally long or elevated metatarsal bone, other differences in foot anatomy, family history, increased age, traumatic injury to the big toe, and female sex.7

Failure of the first metatarsal to achieve sufficient plantar flexion prior to the propulsive phase of gait may prevent the posterior glide of the metatarsal head,10,11 resulting in abnormal hallux dorsiflexion, with impingement of the first metatarsal and the proximal phalanx causing pain and inflammation.12,13 In addition, altered foot and ankle kinematics associated with such pain may be a precursor to OA changes in the first MTP joint.14,15

“It’s not a pathology but a mechanical action that takes place when the first ray doesn’t plantar flex actively and there’s a spur on the dorsal aspect of the first MTP joint,” said Roger Marzano, LPO, CPed, vice president of clinical services for Yanke Bionics in Akron, OH. “The inability of the proximal phalanx to glide dorsally at the first met head is a component of either hypermobility of the first ray, forefoot varus, or both in combination.”

Hallux limitus can result from lack of use of the joint, as well, as patients adopt avoidance strategies to compensate for pain.16

Figure 1. Illustrations depict normal great toe movement (top) and its impairment in a patient with hallux limitus (bottom). (Images courtesy of James Clough, DPM.)

Footwear modifications and foot orthoses are widely used in clinical practice to treat this condition, but their effectiveness has not been rigorously evaluated.17 Surgery may be performed during the course of hallux limitus to remove bone spurs to relieve pain, to add a synthetic “bumper” in the joint, and, if the disorder advances to hallux rigidus, to fuse the joint for pain relief.18

“What starts as a functional restriction of range of motion with no arthritis in the big toe joint progresses to the beginning of early arthritis with bone spurs limiting motion but the toe still able to function. Then progressive arthritis occurs with more and more limitation as the windlass mechanism fails to work and the great toe is completely locked up in hallux rigidus,” said James G. Clough, DPM, who practices at the Foot and Ankle Clinic of Great Falls, MT.

The incidence of hallux limitus has increased in recent years, according to Georgeanne Botek, DPM, who practices at the Diabetic Foot Clinic of the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. She attributes this largely to an aging but active population.

“Patients in the past would present in their mid-forties, but now we see increasing numbers in their sixties and seventies,” Botek said. “With their increased physical activity and greater awareness of health issues, they present with more symptomatic and severe cases.”

The condition affects one of every 45 middle-aged persons and 35% to 60% of the population older than 65 years, according to a 2017 review.3

Orthotic management

Orthotic devices for hallux limitus are designed to limit motion across the first MTP joint while providing cushioning and plantar pressure distribution. Many practitioners bemoan the paucity and quality of research on conservative treatment of this disorder, as it leaves them to find what works best in their individual view.

One recent review19 found high-quality studies supporting orthoses, manipulation, and intra-articular injections. However, nonoperative management should still be offered prior to surgical management, the authors wrote.

A 2010 paper in the Journal of Foot and Ankle Research9 noted most publications on orthotic management of hallux limitus were small case studies,10,20,21 though a number of studies had looked at the effect of orthotic devices on first MTP joint function in healthy or asymptomatic individuals.22-28

But conservative care, including orthotic management, often leads to symptomatic relief. Grady et al, in a retrospective analysis of 772 patients with symptomatic hallux limitus, found 55% were treated successfully with conservative care.29 Of those, 84% were given foot orthoses. Overall, 47% of the patients in the analysis were treated successfully with orthoses. Other conservative care in the study included corticosteroid injections and changes in footwear.

“In mild cases, the goal is to allow protected movement, and in more severe cases, to block movement of the first MTP joint,” said Howard Kashefsky, DPM, FACFAS, director of podiatry services at the University of North Carolina Hospitals in Chapel Hill.

With or without orthotic treatment, hallux limitus may progress to hallux rigidus. Whether orthotic management can delay the progression of hallux limitus, however, is unclear.

Figure 2. Graphic depiction of hallux rigidus, the endpoint of hallux limitus progression. (Image courtesy of Roger Marzano, LPO, CPed.)

“No orthotic will ever take away the progressive arthritic condition, and in the end, most people wind up coming back for surgery,” said Samuel Adams, MD, assistant professor of orthopedic surgery and director of foot and ankle research at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC.

Kashefsky said he knows of no studies that suggest orthoses can help delay or stop progression. However, he said, “I do have a population that seems to respond well to orthotics and conservative care for years. Some can avoid surgery for their lifetime, based on their life stage, activities, and expectations.”

Referring to orthoses and other conservative management strategies for hallux limitus, Clough said, “If it is found in an early stage with good range of motion, minimal spurring, and the ability to engage the windlass mechanism with adequate mobility of the big toe joint, I believe you can maintain mobility and prevent the deformity from progressing.”

Increasing dorsiflexion at the first metatarsal joint, by reducing inflammation and implementing physical therapy, does produce symptomatic improvement, according to Paul R. Scherer, DPM, founder of ProLab Orthotics in Napa, CA, and a clinical professor at the Western University College of Podiatric Medicine in Pomona, CA.

“But what we do not know is whether that relates to physiologic change in the joint. Have you really prevented further physiologic damage down the road? For that you might need to gather forty patients and follow them for ten years to get enough data for a possible answer,” Scherer said.

Device design

If patients are in early phase of the continuum with pain only at the end of their ROM, many practitioners start orthotic management with a flexible cork Morton’s extension and a rocker added to the shoe. In later stages, as joint deterioration increases and movement becomes more painful throughout its range, more rigid orthotic materials such as fiberglass are employed, along with a stiffer shoe and a rocker sole.

Pain only with compression of the first MTP joint, also known as “grind testing,” and pain during the middle of ROM may indicate advanced arthritis,3 a prognosis Kashefsky said should be addressed with a stiffer orthotic device.

Adams said he would offer an orthotic device for relief of minor pain, usually either a Morton’s extension by itself or with a full-length device.

“Our physical therapists might also put in a pad under the MTP joint to increase range of motion,” he said.

Kashefsky said he checks the patient’s family history for prognostic clues. He assesses passive and active ROM using a goniometer, gets weightbearing x-rays, and checks manually for the exact location of pain, including under the sesamoids and at the metatarsal-medial cuneiform joint. Sesamoid deformities, which can result from arthritis, trauma, or necrosis, can contribute to pain under the joint and warrant treatment with a stiffer orthosis, Kashefsky said.

A hypermobile first ray, he said, can contribute to abnormal first-ray elevation.30 He also looks for the presence of bone fragments in the joint, gout, between-limb symmetry of any arthritis, and any changes suggestive of seropositive/seronegative arthritis or trauma.

Materials are chosen based on a patient’s age, weight, activity level, and preferred type of activity.

“I prefer a Morton’s extension with something soft like cork for hallux limitus and fiberglass for hallux rigidus,” Kashefsky said.

The fiberglass extension is commonly used when large football players incur turf toe from trauma to the first MTP joint, he said. Marathon runners in his clinic typically run with cork extensions under the great toe.

“I encourage them to run at a high cadence and a short stride to avoid over-striding, and pair that with thickly cushioned, ‘maximalist’ running shoes,” which, he said, helps runners tolerate low levels of first MTP pain over a long period.

Scherer uses principles he and others set out in a 1996 hypothesis,31 for which they confirmed clinical applicability in 2006.26 It rests on the idea that first-ray dorsiflexion increases ROM at the first metatarsal joint.

“I don’t think you will find a practitioner today who wouldn’t plantar flex the first ray when casting for orthotics and provide minimum fill, as well as use a reverse Morton’s extension in an orthotic prescription for functional hallux limitus,” he said. “There’s not much evidence for anything else in this arena.”

Plantar flexion is essential, Clough agreed, to eliminate any elevation of the metatarsal joint that could cause jamming of the motion and eliminate any forefoot supination.

To avoid eversion of the rearfoot, which has been reported to be associated with hallux dorsiflexion,32 Clough doesn’t use a first metatarsal head cut-out, because it would eliminate a rigid point of stability. But he always uses a slight wedge of about 4 mm under the hallux.

“That allows the hallux to dorsiflex unimpeded and the first metatarsal to plantar flex as the patient moves forward in propulsion,” he said. “It helps reorient ligaments around the first MTP joint so they don’t restrict mobility there. It also eliminates any forefoot supination.”

Marzano recommends a first-ray cut-out.

“Some pocket or relief is given under the first metatarsal head to stimulate plantar flexion of the first ray at the heel-off phase of gait,” he said.

A recent Spanish publication found a cut-out orthosis significantly increased declination of the metatarsal angle and demonstrated a positive effect on the affected joints.33 The cut-out also significantly reduced adduction movement of first metatarsal bone in the transverse plane.

“If the cut-out alone does not resolve the symptoms, I utilize a medium density carbon fiber footplate contoured to the shoe,” Marzano said. He explained that an orthosis might fail if a practitioner picks a flat foot plate for a shoe with a large heel rise and great toe spring.

Figure 3. Radiographs of a patient with bilateral hallux limitus. (Images courtesy of Georgeanne Botek, DPM.)

Because people with hallux limitus often roll their foot laterally to avoid putting weight on the big toe, lateral wedging the full length of the orthosis may be employed, partly to address any subconscious, compensatory movements that might cause problems, Marzano said.

“Peroneal tendinitis can occur from rolling the foot laterally because it hurts to push off. That repetitive rob-Peter-to-pay-Paul mechanism can irritate the peroneal longus tendon, which is a significant plantar flexor of the first ray,” he said.

Metatarsal pad utilization depends on the size and shape of the metatarsal heads, Botek said.

“You’re probably off-loading the first, second, and third heads, or perhaps the entire MTP area, as opposed to just having a cut-out for the first ray,” she said. “A metatarsal bar could be placed on the shoe, and some orthotics come with a built-up met bar to offload the entire metatarsal head region.”

For Botek, an orthosis for most people with moderate to severe cases of hallux limitus starts with a thin carbon fiber insert fit to the proper shoe size.

“It extends just beyond the first metatarsal head, providing a little propulsive plate under an insole, and in my experience, helps some seventy percent of patients,” she said.

Alex Kor, DPM, immediate past president of the American Academy of Podiatric Sports Medicine, said that though typically the cut-out in an orthosis will stop just proximal to the metatarsal head, the orthotists he works with will, at times, extend the rigid part of the device beyond the first metatarsal head to help facilitate push off.

But Kor, who practices at Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin Health System in Milwaukee, noted there are always exceptions.

“I had a semiactive, weekend-warrior type of woman who couldn’t tolerate the longer first ray Morton’s extension, so we cut it back, and that eliminated her pain,” he said. “Prescribing orthotics is an art and a science. There’s no one size fits all.”

Custom or over the counter?

Disagreements abound over whether to start orthotic management with custom or over-the-counter (OTC) devices.

Welsh et al conducted a case series of 32 patients with first MTP joint pain in which modified prefabricated foot orthoses were associated with significantly reduced pain at 24 weeks.9 However, a control group was not included in that study.

Botek estimates about 80% of patients find an OTC option that helps.

“People are relying more on off-the-shelf orthotics now because the devices incorporate better technology,” she said. “The most common accommodation for hallux limitus is a metatarsal pad to help offload the entire forefoot, and some OTC inserts and even some footwear come with that. So, I start with those, unless something is clearly out of line mechanically, and if pain relief is not adequate we may prescribe a custom device.”

In Botek’s experience, improvements in prefabricated orthotic technology have led to decreased use of anti-inflammatory medications; as an alternative, she recommends topical analgesics along the great toe.

Kashefsky agreed some off-the-shelf devices can be helpful, but said the inserts’ shape must match the foot’s architecture.

“If there’s a mismatch, a custom device is indicated,” he said.

Kor has a strong preference for custom orthoses, but acknowledges that isn’t always practical.

“Orthotics are a work in progress, and that’s why the best are custom-made. There’s an art to this, and I want to work with an orthotist who’s flexible enough to try different things,” he said. “But off-the-shelf orthotics definitely can be tried. We have to deal with reality, as insurance isn’t often covering orthotic adjustments. I tell patients to try the store-bought device and bring it to me after a couple of weeks’ use so I can customize it to the foot.”

Clarke Brown, PT, DPT, said customization is also a priority for his group, BrownStone Physical Therapy in Rochester, NY.

“Our group prefers custom orthoses, which allow you to add and subtract material for specific patient conditions,” Brown said.

At least one visit to physical therapy is often prescribed for a range of treatments, including stretching, manipulation, ultrasound, and balance board, to achieve a strengthened foot with maximal ROM in the big toe joint and lack of tightness of the gastrocnemius- soleus unit, he said.

“Our takeaway is to use orthoses to maximize the physical therapy treatment,” Brown said. “Make the orthosis the last, not first thing you do when treating hallux limitus or other foot problems.”

Marzano also has personally observed that gastrocnemius-soleus contractures are often present in runners with symptomatic hallux rigidus and have limited dorsiflexion due to highly developed musculature, as well as in runners who spend too little time stretching.

“If you don’t have range of motion at the ankle joint because of Achilles contracture, you’re exacerbating the hallux rigidus symptoms due to a necessary increase in metatarsophalangeal extension, as compensation for the decreased ankle range of motion,” he said.

Botek said in addition to orthotic treatment, she also instructs her patients to perform a prescribed series of toe-joint motion and distraction exercises with an emphasis on great toe ROM while both weightbearing and nonweightbearing.

Scherer said he refers patients for physical therapy, but typically does so after orthotic fitting.

“I personally construct the orthotic first, but I don’t think there’s any literature to say which [order] is best,” he said. “It’s based on anecdotal, personal preference.”

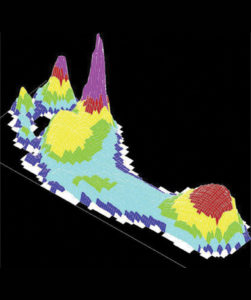

Figure 4. Elevated plantar pressures under the great toe in a patient with hallux limitus in shoegear. (Image courtesy of Georgeanne Botek, DPM.)

Footwear considerations

Shoe choice is critical to the success of orthotic treatment for hallux limitus, several practitioners said. Brown starts with a flat housing and a neutral shoe (no bias toward a curved or straight last), laces, sufficient width for the orthosis, and no wedge or roll bar.

“However, fashion preferences and workplace requirements may force you to deal with a different shoe,” he said, a statement many others echoed.

Botek said she looks for a Vibram- or rubber-soled shoe with laces to hold the orthosis firmly in place. In particular, the shoe should accommodate the device’s depth, which can be a challenge, she said. Some patients turn to steel-toed footwear for a toe box of adequate size. High and wide toe boxes may also help prevent compression of dorsal osteophytes.3

Kashefsky’s ideal shoe to pair with orthoses should have a rocker sole, be stiff enough to protect the great toe joint, and allow for shock absorption. It also should have a removable liner or other means of making room for the device.

Marzano warned that many orthotic professionals construct devices well, “but then [patients] stuff them into shoes that may not have adequate volume.”

Runners in particular, he said, don’t understand that this is critical to the success of the orthosis.

“Some don’t realize their feet have gotten longer and wider as they’ve aged,” he said.

Many athletic shoe manufacturers offer both medium and wide widths, Marzano said, but depth can still be an issue relative to the dorsal prominences present in many runners with hallux limitus.

In patients with later stages of hallux limitus, with erosion at the first metatarsal joint and arthritic changes occurring, Marzano said he moves aggressively in orthotic management. One of his patients, aged 72 years, wanted to continue playing doubles tennis three times weekly with only 5° of ROM at the first MTP joint. A cardiac condition made surgery untenable, so, “every year I take two pairs of his preferred tennis shoe and bury steel shanks in the bottom and add a mild rocker sole. That’s something I wouldn’t do for a forty-five-year-old,” Marzano said.

The popularity of shoes that lack structure may contribute to first metatarsal joint issues, he said.

“People need to think of their shoes as a therapeutic device versus being just a piece of apparel. I think some MTP joint problems may come from wearing shoes you can bend in half with one hand and don’t provide any structural integrity or any resistance at all to toe motion,” Marzano said. “I see fewer leather-soled, rubber-heel shoes now, and no steel shanks, either.”

In patients with early hallux limitus, a shoe should bend on the ball of the foot right behind the toes with nothing to impede great toe motion, Clough said.

“We want mobility and flexibility at first, to allow the toe to bend absolutely freely,” Clough said. “In later stages, where there is structural limitation and not enough motion available to provide stability of the medial arch when the toe isn’t actually dorsiflexed, we look to stiffer soles and rocker bottom shoes.”

Hank Black is a freelance writer in Birmingham, AL.

- Lucas DE, Hunt KJ. Hallux rigidus: relevant anatomy and pathophysiology. Foot Ankle Clin 2015;20(3):381-389.

- Gould N, Schneider W, Ashikaga T. Epidemiological survey of foot problems in the continental United States: 1978-1979. Foot Ankle 1980;1(1):8-10.

- Ho B, Baumhauer J. Hallux Rigidus. EFORT Open Rev 2017;2(1):13-20.

- Laird PO. Functional hallux limitus. Illinois Podiatrists 1972;9(4).

- Mann RA. Hallux rigidus. Instruc Course Lect 1990;39:15-21.

- Smith RW, Katchis SD, Ayson LC. Foot Ankle Int 2000;21(11):906-913.

- Zammit GV, Menz HB, Munteanu SE. Structural factors associated with hallux limitus/rigidus: a systematic review of case control studies. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2009;39(10):733-742.

- Arden N, Nevitt MC. Osteoarthritis: Epidemiology. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2006;20(1):3-25.

- Welsh BJ, Redmond AC, Chockalingam N, et al. A case-series study to explore the efficacy of foot orthoses in treating first metatarsophalangeal joint pain. J Foot Ankle Res 2010;3:17.

- Michaud TC. Pathomechanics and treatment of hallux limitus: A case report. Chiropr Sport Med 1988;2(2):55-60.

- Shereff MJ, Bejjani FJ, Kummer FJ. Kinematics of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1986;68(3):392-398.

- Lichniak Hallux limitus in the athlete. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 1997;14(3):407-426.

- Shereff MJ, Baumhauer JF. Hallux rigidus and osteoarthrosis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998;80(6):898-908.

- Drago JJ, Oloff L, Jacobs AM. A comprehensive review of hallux limitus. J Foot Surg 1984;23(3):213-220.

- Piscoya JL, Fermor B, Kraus VB, et al. The influence of mechanical compression on the induction of osteoarthritis-related biomarkers in articular cartilage explants. Osteoarthr Cartilage 2005;13(12):1092-1099.

- Botek G, Anderson MA. Etiology, pathology, and staging of hallux rigidus. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 2011;28(2):229-243.

- Menz HB, Levinger P, Tan JM, et al. Rocker-sole footwear versus prefabricated foot orthoses for the treatment of pain associated with first metatarsophalangeal joint osteoarthritis: study protocol for a randomized trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:86.

- Baumhauer JF, Singh D, Glazebrook M, et al. Prospective, randomized, multi-centered clinical trial assessing safety and efficacy of a synthetic cartilage implant versus first metatarsophalangeal arthrodesis in advanced hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int 2016;37(5):457-469.

- Kon kam king C, Loh sy J, Zheng Q, et al. Comprehensive review of non-operative management of hallux rigidus. Cureus 2017;9(1):e987.

- Harradine PD, Bevan LS. The effect of rearfoot eversion on maximal hallux dorsiflexion. A preliminary study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2000;90(8):390-393.

- Smith C, Spooner SK, Fletton JA. The effect of 5-degree valgus and varus rearfoot wedging on peak hallux dorsiflexion during gait. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2004;94(6):558-564.

- Nawoczenski DA, Ludewig PM. The effect of forefoot and arch posting orthotic designs on first metatarsophalangeal joint kinematics during gait. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2004;34(6):317-327.

- Halstead J, Turner DE, Redmond AC. The relationship between hallux dorsiflexion and ankle joint complex frontal plane kinematics: a preliminary study. Clin Biomech 2005;20(5):526-531.

- Scherer PR, Sanders J, Eldredge DE, et al. Effect of functional foot orthoses on first metatarsophalangeal joint dorsiflexion in stance and gait. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2006;96(6):474-481.

- Munuera PV, Dominguez G, Palomo IC, Lafuente G. Effects of rearfoot-controlling orthotic treatment on dorsiflexion of the hallux in feet with abnormal subtalar pronation: a preliminary report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2006;96(4):283-289.

- Munteanu SE, Bassed AD. Effect of foot posture and inverted foot orthoses on hallux dorsiflexion. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2006;96(1):32-37.

- Grady JF, Axe TM, Zager EJ, Sheldon LA. A retrospective analysis of 772 patients with hallux limitus. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2002;92(2):102-108.

- Roukis TS, Jacos PM, Dawson DM, et al. A prospective comparison of clinical, radiographic, and intraoperative features of hallux rigidus: Short-term follow-up and analysis. J Foot Ankle Surg 2002;41(3):158-165.

- Roukis TS, Scherer PR, Anderson CF. Position of the first ray and motion of the metatarsophalangeal joint. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1996;86(11):538-546.

- Harradine PD, Bevan LS. The effect of rearfoot eversion on maximal hallux dorsiflexion. A preliminary study. J Am Pod Med Assoc 2000;90(8):390-393.

Dear all,

Great article!

I am researching the possible corelation between the use of insoles for hallux limitus and medial knee tendinitis.

I am possibly rolling out but then back in thus irritating medial tendons?

As I am writing this I feel I should get myself videoed and do some ectra stability & knee tracking work to strengthen my glutes/hips etc?

Any advice welcome! Many thanks!

Kind regards,

Eric