By Emily Delzell

By Emily Delzell

US orthopedic surgeons perform more than 25,000 microfractures annually, making the procedure the most common marrow-stimulating technique used for repair of the cartilage defects that often affect active individuals.1 Although microfracture is a single-stage, low-cost intervention that requires only surgical time and common surgical tools, it requires a lengthy rehabilitation and comes with other challenges, such as limited durability and less than optimal return-to-sport rates. And, for many patients, the procedure also comes as a complete surprise.

Shawn Reed, an avid mountain biker with a history of knee problems, first heard the term microfracture when he woke in recovery after a meniscus surgery to his right knee. He told LER that before the operation he’d understood the surgery would be, to some extent, exploratory. Still, the rehabilitation process, which he also learned about for the first time that day, was a big surprise.

“The orthopedic surgeon told me he’d found some significant tears in my meniscus, that he’d cleaned all the tears up, and then said he’d found an unusual cartilage tear on my femur, basically a big pothole in the cartilage, and that he’d done microfracture on that area. He went on to say I’d be on crutches for about six weeks, and that, hopefully, three to four months down the road, I could get back to a good activity level,” Reed said.

“I was a little confused from the anesthesia, but my wife was there, and I turned to her when he left and asked, ‘Did he just say I’m off my feet for six weeks?’ It was also a little confusing because he presented this to me in a very matter-of-fact way,” said Reed, a 45-year-old Raleigh, NC, resident whose job as a cardiovascular sales representative requires lifting and carrying boxes in and out of physician offices.

Reed had undergone several previous surgeries to his other knee, including a meniscus repair that was followed by a relatively easy and brief recovery. So he went into his most recent procedure with a confident, even casual attitude, thinking he’d be up and walking in two or three days.

Although Reed wishes he’d known about the potential for a long recovery before surgery, he acknowledges that he should have asked more questions and that he told his surgeon to make whatever intraoperative decisions he deemed best—to “treat the knee as if it were his own.”

“I essentially gave him a green light to go ahead with whatever he thought would be best,” said Reed, who noted he was extremely fortunate to have an employer that provides temporary disability benefits as well as good coverage for physical therapy.

“I was lucky to be able to go on short-term disability really unexpectedly,” he said. “I was out for the full six weeks, which allowed me to be very compliant with rehabilitation.”

His insurance coverage will also allow him to continue physical therapy for as long as he and his therapist thinks it’s required, and his flexible field-based job means he can find time to make it to the twice-weekly therapy sessions that have so far focused on quadriceps and range of motion exercises.

Not all patients who end up with a “surprise” microfracture have Reed’s security net and other resources.

For Graham Cole, a 59-year-old independent contractor in Caerphilly, Wales, who has no sick leave benefits, the weight-bearing restrictions that came with his recovery from microfracture have been financially devastating and the procedure highly unsatisfactory.

Ten weeks after his surgery Cole was struggling with considerable pain and fearing he would never be able to return to squash, which he’d previously played well enough to have a shot at the number-one spot in the national rankings for his age group.

“I was told [before the surgery] I could expect to walk from the hospital and resume sport in about a fortnight,” said Cole, who was on a surgical waiting list for 36 weeks after being told he needed a meniscus trim.

“The surgery [the meniscus trim] sounded promising, but after all that time I was slightly hesitant as the knee seemed to be improving steadily and I was back cycling and playing squash, albeit poorly and in a brace,” he said. “But I had no idea this [the microfracture] would be done!”

Cole described himself as “massively disappointed and depressed,” noting that he was told about the microfracture “fourth hand,” has never spoken to the surgeon who did the procedure, and has not received good advice about the rehabilitation he needs beyond six weeks.

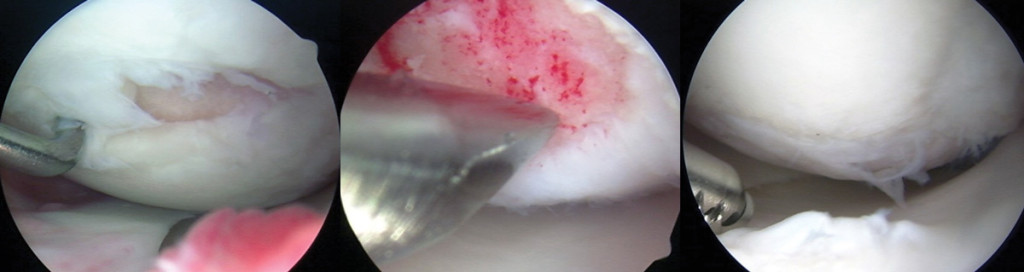

Left arthroscopic image shows grade 4 lesion, 21 x 7 mm, on the medial femoral condyle prior to microfracture. Center image shows perforations of exposed subchondral bone during microfracture. Right image, two years postmicrofracture, shows filling of all of the previous microfractured defect with some grade 2 fraying. (Photos courtesy of Karen Briggs, MPH, director, Center for Outcomes-Based Orthopaedic Research, Steadman Philippon Research Institute, Vail, CO.)

“I wish I’d never had this done; it’s really ruined my life in some ways,” he said. “I am just hopeful that my situation will improve.”

He is doing his own research on microfracture recovery and is trying to follow the later phases of the rehabilitation protocol designed by the orthopedic surgeon who developed microfracture, Richard Steadman, MD.2

Steadman told LER he would never perform microfracture without first discussing the procedure and the recovery fully with the patient.

“Having a patient who is willing to be compliant with the rehabilitation protocol is very important to the success of microfracture,” explained Steadman, who, along with colleagues at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, developed microfracture in the 1980s through studies on horses.

“Most of my patients are referred to me for microfracture, so they already know they have the problem. If they have a reasonable MRI, which all of our patients have, then we just don’t find a surprising defect,” he said. “In thousands of cases, I can only think of this happening once or twice. It’s not difficult to determine the depth and location of defect on MRI and talk the situation over before the surgery; that way you don’t get caught in the middle of case.”

Imaging, imaging, imaging

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can produce high quality images of cartilage defects, not all MRI units are created equal, explained Riley J. Williams III, MD, an orthopedic surgeon at Manhattan’s Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS), where he is also a member of the Sports Medicine & Shoulder Service and director of the HSS Institute for Cartilage Repair.

“It [image quality] depends on the size of magnet involved as well as the software the individual unit is using,” he said. “Overall, there are many more MRI units out there now [than in the 1990s] that can detect the presence of articular cartilage damage, but the clarity of those images is still highly variable from unit to unit.”

Aaron Krych, MD, associate professor of orthopedic surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, noted, “Certainly, with the availability of three-Tesla cartilage mapping, MRI has become very good at diagnosing the lesion, helping us size the lesion. Surprises can come when there is a poor quality MRI or the classic case in which surgeons have, for example, an ACL patient whose initial injury films [may not indicate a need for microfracture], but then [the patient experiences] subsequent instability between their MRI and the current surgery, which results in more injury and lesions that are found only at the time of surgery.”

Both Williams and Krych feel it’s incumbent on surgeons who perform cartilage defect repairs to ensure their patients undergo MRI in a unit that’s up to the task of determining defect depth and location clearly

“It’s not up to the MRI operator or the radiologist to ensure the doctor sees what they need to see,” Williams said. “If you’re a surgeon and this is an area of interest for you, then it’s very easy to engage with the radiologist, because these changes in detection that are required are fairly simple adjustments.”

He noted that he’s pinpointed all five of the MRI units within a two-mile radius of his hospital that image cartilage well.

“If I’m suspicious of cartilage damage, I’ll be sure to get them into one of those units,” he said,

Like Steadman, both Krych and Williams said they would never perform a microfracture without first explaining the factors involved and getting consent from the patient.

“It radically alters their rehab,” Krych said. “Instead of undergoing a simple knee debridement from which they quickly recover, microfracture means six weeks of crutches plus use of a continuous passive motion [CPM] machine six to eight hours a day. I imagine a lot of patients wouldn’t be too happy with that unless they’d agreed to it first.”

Williams noted that patients who aren’t expecting the microfracture often end up with the worst results.

“The surgeon hasn’t had time to prepare the patient and the microfracture is done as a stopgap measure because the surgeon wants to try and do something,” he said. “The big take-home message is imaging, imaging, imaging, because you never want to be stuck doing an operation that is not ideally suited to the patient.”

Other postsurgical surprises

Microfracture wasn’t a surprise for every patient LER talked to. When Harold Rosenberg, a 60-year-old Los Angeles-area resident, heard and felt something in his left knee tear during one of his frequent tennis matches, his surgeon told him his MRI showed a torn meniscus and possibly some other damage for which microfracture might be indicated.

Rosenberg wasn’t told, however, what microfracture recovery typically entails.

“I was never given the information on how difficult that recovery would be,” said Rosenberg, who underwent the procedure in January. “I thought I knew what I was I was getting into. I’d previously had meniscus tears in my other knee and went in for surgery, and ten days later I was up hitting tennis balls, so I thought, okay, I’ll do this.”

Rosenberg said his surgeon never discussed the need to avoid full weightbearing.

“I used crutches for a couple of days and then put them away,” he said. “I felt pretty good for a while, but then the pain really increased.”

Rosenberg tried doing the exercises he’d learned in his first physical therapy session, but experienced too much pain to continue, possibly because he’d stressed the healing cartilage too early in his recovery.

“The best thing that I did was doing nothing for two weeks, then the pain sort of subsided, and I’m doing exercises the therapist prescribed,” he said.

About 10 weeks into his recovery, Rosenberg could walk without pain, but said he couldn’t run and that some movements, such as pivoting, were still painful.

At a follow-up appointment with his surgeon in late March, Rosenberg questioned his surgeon about what he had since learned about the typical rehabilitation involved in microfracture. The surgeon told him that he hadn’t recommended limited weightbearing because Rosenberg’s defect was not in a weightbearing area, but that he would have recommended the restriction had the defect been in a more vulnerable location.

Rosenberg’s surgeon also skipped prescription of CPM. So did Graham Cole’s and Shawn Reed’s. Reed asked his surgeon about using CPM and was told he didn’t need it. However, all the surgeons interviewed for this article said they prescribe CPM for six to eight hours a day during the first phase of recovery.

“We think that CPM gives a message to this new-forming tissue that it wants to be a smooth surface, that it wants to firm, and that it has time to develop the type of cartilage that will stand over the long haul,” Steadman said.

Krych agreed.

“Most of the time with knee surgery, CPM is used to encourage motion. However, in cartilage surgery, the CPM is actually to promote good cartilage metabolism without overloading the cartilage, as the knee has protected weightbearing,” he said. “Most surgeons who perform a significant number of cartilage repair procedures would use CPM on all cartilage patients unless insurance denies it.”

A recent survey of surgical practice among Canadian orthopedic surgeons suggests many who perform microfracture don’t use CPM.3 Investigators received 299 responses from members of the Canadian Orthopaedic Association; 131 reported regularly performing microfracture. Only 11% said they prescribed CPM and 39% didn’t restrict weightbearing. Sports surgeons had significantly higher use of CPM and of restricting weightbearing than surgeons without a sports medicine practice.

In a systematic review of the clinical evidence for use of CPM after repair of cartilage defects of the knee,4 investigators from The Ohio State University in Columbus identified four level III studies that met their inclusion criteria, but no randomized controlled trials. Because of the wide range of procedures used for repair, they couldn’t perform a meta-analysis and, therefore, couldn’t reach any definitive conclusions about the efficacy of CPM. However, they noted that basic science strongly supports the use of CPM in this setting.

Durability and return to sports

Most research and experts agree that microfracture produces the best results in younger patients with single lesions that are relatively small and well-defined.5-9

“In our studies6,9 looking prospectively at the efficacy of microfracture we identified age less than thirty, BMI [body mass index] less than twenty five, and defect size less than 2.5 cm2 [as factors associated with better outcomes],” Williams said. “In addition, lesions that are on the weight-bearing surface of the femoral condyle do better than those that are in the patellofemoral joint.”

Krych also noted that he considers the presence of symptoms for less than 12 months a positive prognostic indicator.

“As these defects become more chronic, more muscle is lost, the leg is more deconditioned, and it’s harder for patients to come back to previous activity levels,” he said. He also stressed the importance of a BMI below 30, noting, “Some insurance companies have stopped approving microfracture for patents with BMIs higher than thirty.”

For Williams, the return-to-sports rate even in the ideal patient is unacceptably low, and he has not used microfracture as a primary procedure for cartilage defect repair for several years.

“Research we published in 200610 on the return to athletics following microfracture—and this was in high-level athletes, young, highly motivated, conditioned individuals—showed the return-to-sports rate [at follow up of two years or longer] was only forty four percent, so I started to migrate away from that particular strategy,” Williams said.

Durability of the repair is a concern, as well. A 2009 review of 28 studies by Mithoefer et al, for example, showed that, while microfracture produced improvements in knee symptoms during the first two years after surgery, seven of the studies included in the review reported functional declines in 47% to 80% of patients after 18 to 36 months.11

Steadman, however, has reported good long-term results. His 2003 study of 68 patients who underwent microfracture between 1981 and 1991 showed significant improvements in pain and knee function an average of 11.3 years after microfracture.12 A second 2003 study13 by Steadman et al reported good return-to-sports rates: Of 25 active National Football League players treated with microfracture between 1986 and 1997, 19 returned to professional play an average of 10 months following the procedure. Each returning athlete played in an average of 57 NFL games (range, 2-180 games) following microfracture. Six of the athletes retired; all but one had played at least five years in the NFL and three had played more than 10 years.

Steadman told LER his good results may be related to the eight weeks—not six—that orthopedic surgeons at The Steadman Clinic in Vail, CO, keep their patients on crutches.

“People have cut it down to six weeks, and it may be that that is an appropriate time, but, based on our work in horses, we have continued the eight-week protocol,” he said. “You want to avoid heavy weightbearing, but you can swim or you can spin on a bike after one or two weeks, so you can be active, but you don’t want to put a lot of pressure on the immature tissue that’s forming.”

Like Williams, Krych said he is using microfracture less often.

“I think we’re somewhat biased here because we see a lot of failed microfracture, so I tend to do an ACI [autologous chondrocyte implantation] or an [osteochondral] transfer, but that’s probably just my practice,” he noted. “I would say we’ve trended away from microfracture, depending on the activity goal of the patient, but we do still use it in select cases where it’s a small, well-contained lesion on a well-aligned knee.”

He noted that while the surgery is cost effective, its costs to patients are significant.

“If we have a procedure that puts them through the same rehab but is more durable [such as an osteochondral autograft transfer], I’m more willing to offer them that—especially if they are a young higher-demand athlete—doing a transfer over microfracture in those situations is probably better,” he said.

Despite his rehabilitation challenges, Rosenberg has a relatively positive attitude about his microfracture and his likely outcome.

“I wish I’d had more knowledge about what to expect postoperatively in terms of pain and more instruction about not weightbearing [fully] for the first few weeks,” he said. “But, even knowing all that, I would probably still go ahead and have this done. I’m optimistic that they didn’t have me go through this for nothing, and that I’ll be able to get to a fairly good level of activity. But I also know that this is going to be a temporary fix that will maybe last the next three to five years.”

1. McNickle AG, Provencher MT, Cole BJ. Overview of existing cartilage repair technology. Sports Med Arthrosc 2008;16(4):196-201.

2. Hurst JM, Steadman JR, O’Brien L, et al. Rehabilitation following microfracture for chondral injury in the knee. Clin Sports Med 2010;29(2):257-265.

3. Theodoropoulos J, Dwyer T, Whelan D, et al. Microfracture for knee chondral defects: a survey of surgical practice among Canadian orthopedic surgeons. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012;20(12):2430-2437.

4. Fazalare JA, Griesser MJ, Siston RA, Flanigan DC. The use of continuous passive motion following knee cartilage defect surgery: a systematic review. Orthopedics 2010;33(12):878.

5. Solheim E, Øyen J, Hegna J, et al. Microfracture treatment of single or multiple articular cartilage defects of the knee: a 5-year median follow-up of 110 patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010;18(4):504-508.

6. Williams RJ 3rd, Harnly HW. Microfracture: indications, technique, and results. Instr Course Lect 2007;56:419-428.

7. Gobbi A, Nunag P, Malinowski K. Treatment of full thickness chondral lesions of the knee with microfracture in a group of athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2005;13(3):213-221.

8. Gobbi A, Karnatzikos G. Microfracture treatment of grade IV knee cartilage lesions: results at 15-year follow up in a group of athletes. Presented at Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, Chicago, March 2013.

9. Mithoefer K, Williams RJ 3rd, Warren RF, et al. The microfracture technique for the treatment of articular cartilage lesions in the knee. A prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87(9):1911-1920.

10. Mithoefer K, Williams RJ 3rd, Warren RF, et al. High-impact athletics after knee articular cartilage repair: a prospective evaluation of the microfracture technique. Am J Sports Med 2006;34(9):1413-1418.

11. Mithoefer K, McAdams T, Williams RJ, et al. Clinical efficacy of the microfracture technique for articular cartilage repair in the knee: an evidence-based systematic analysis. Am J Sports Med 2009;37(10):2053–2063.

12. Steadman JR, Briggs KK, Rodrigo JJ, et al. Outcomes of microfracture for traumatic chondral defects of the knee: average 11-year follow-up. Arthroscopy 2003;19(5):477-484.

13. Steadman JR, Miller BS, Karas SG, et al. The microfracture technique in the treatment of full-thickness chondral lesions of the knee in National Football League players. J Knee Surg 2003;16(2):83-86.

As a previous collegiate athlete (a.k.a….an “ideal,” motivated patient prepared to follow all the recovery protocols) who has undergone a failed microfracture and an osteochondral autologous transfer (OATS) procedure, I am left pondering one major question on this topic. As your article lightly hints at, why do so many surgeons still use microfracture as a first line of defense against these chondral defects? The rate of success is low and the rehab protocols for the different procedures are fairly similar, so it is not really a matter of convenience to the patient. I certainly wish in my history I had been sent straight to the table for the OATS procedure. The theory behind ACI (Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation) is also very viable and simply amazing, albeit expensive and complicated. I guess it’s because microfracture is more convenient for the surgeon? Poke a bunch of holes? (Of course experience is key, and it sounds like the Steadman Clinic has better results then elsewhere.) But, if the microfracture fails, as a patient you’re left with close to 2 months on crutches, then a few months of rehab before you even reach a level of activity to suspect something failed. It adds up very quickly to maybe half a year, only to start all over again. Thank you for addressing this subject. I think anyone facing a prospective microfracture surgery will greatly appreciate your article!

I’m simply amazed by Shawn Reed’s story on this article, as his story is very similar to mine. I thought I was going in for a very simple procedure that would guarantee me being on my feet a few days later, I was sadly mistaken. I woke up to the news that I must be on crutches, use the CPM 8hrs x day, and no weigh bearing for 6 weeks. Not exactly the news that a 36yr old very active US Army soldier and paratrooper wants to hear. I’m very disappointed with the fact that I didn’t even have a choice, and here I am, 5 days later laying on my bed, looking at a beautiful FL day out of the window. Can anyone chime in on the consequences of weigh bearing now or later if there’s a big chance that this procedure isn’t going to work in the long run?

As an orthotist with considerable contact with sports orthopedists and as an older very athletic guy with a femoral defect after 2 right ACL tears 20 + years ago I talked to some of the best sports ortho docs I know. Without hesitation they all said the maximum age they would consider would be 35 years old and the minimum rehab was 6-9 months. Additionally they considered it an extremely slow and tedious rehab and that getting the patient, trainers and P.Ts all on the same page was a challenge. Weight bearing activities are very limited in the first few months and very carefully monitored. After reading this article I can see why the failure rate is so high.

I had Microfracture 10 months ago as an active 38 yr old. I was ready, willing and able for the procedure. Started light toe-to-ground at 5 weeks after non-weight bearing, swimming and leg pumping on my back in water at 6-10 weeks. I religiously hit the spinner for 30 minutes a day with little to no resistance until week 11 and then increased. I did endless straight leg lifts and PT. For all this hard work at 10 month, I am still unable to participate in any strenous activities. Microfracture has ruined the life I’ve known and enjoyed. Especially sports and carrying my beautiful young daughters. My Top Sports Doc is now talking about OATS procedure or Denovo Zimmer to plug the 1.5cm focal defect, all other parts of the knee are clean. Microfracture secondary fibro cartilage just doesn’t absorb heavy impact like the hyaline original. I beg you don’t make my mistake and waste your time on what’s easy for insurance and the Doc. Get the Denovo Zimmer procedure if you can or OATS as a go-to if Denovo isn’t coverd by your Insurance.

This article and the previous article (and their comments) are the best I have read on this subject in 5 years. I had my first microfracture at 25. It was a total shock when it happened as the doctor never warned me that I could be on crutches for 6-8 weeks. (The MRI was a total waste of time as it showed nothing) He also NEVER mentioned rehab even after surgery. Just said stay off it and that I was basically retired from any physical activity besides walking…at 25! No rehab was a HUGE mistake. My legs lost significant muscle mass which only put more pressure on the joint. I had a hard time building it back up because there was always a slight stabbing pain where the repair was made so I couldn’t work out at all for nearly 2 years. The other thing they never tell you is to protect the OTHER KNEE. I walked around on crutches, not limiting myself, for 6 weeks only to find my “good” knee hurting 6 months later. My knees finally started to feel normal after 3 years of limited activity. Then my “good” knee started bothering me again at 29. I went to a new doctor fully prepared this time for microfracture again (even though the MRI was total crap again). He was hopeful that he could do the OATS procedure but when he got in, the damage site was too big. Luckily this doctor pushed rehab but when the end of the year occurred after only my second session, I found that the price was EXTREMELY high to go back. (After my first experience, I had the discipline to continue on my own with great results.) DO NOT get this surgery in the last 6 months of the year when your deductible is near resetting. It will cost you big time! This is a LONG process and you’ll want to maximize your deductible. It has now been a year and a half after the second surgery and I’m encouraged to comment on this page only to warn others like I was not warned before. My opinion: DO NOT get this surgery. Discuss scenarios with your doctor before hand if they discover damage requiring microfracture. Different damage sizes have different options. Research OATS and ACI surgeries. I’ve only read a little about ACI but it looks like it would have better suited me. Sure it is an invasive/expensive procedure with a year of rehab but after 6 years of two bad knees and many more ahead of me, 1 year seems like a cakewalk compared to what I have gone through. My knees still feel like they have knives in them when I walk. This stabbing pain comes and goes and lasts 2-4 weeks at a time. I have to significantly reduce my walking (yes simple walking) during this time in order for my knees to stop swelling/aching/stabbing. I am 31. It is such a helpless feeling. The funny (kidding) think about microfracture is that most young people that need it, do so due to their high level of physical activity. But when you get the surgery, you are basically required to do nothing for 2 years if you want a chance of doing ANYTHING beyond then. It’s unrealistic and probably why many of them fail. I suspect that 6 weeks on crutches and limited rehab are just not enough. You need MUCH longer time off the repaired site and your quad strength needs to be BETTER than it was before surgery before you start exercising again. It seems to me that that’s the only way to have a fighting chance. I truly hope this helps someone avoid the pain and frustration this stupid surgery has caused me.

I woke up from a simple meniscus repair only to find that my meniscus was fine but the doctor did microfracture knee surgery for an osteochondral lesion. My husband was in the waiting room the entire time but was never approached for permission to do the different surgery. I’m five weeks postop, and am frankly concerned after reading through these comments. I’ve spent over a thousand on a CPM machine my insurance won’t cover, had to change vacation plans, and had to borrow other equipment since we had no notice of procedure. I go for my six-week follow up on Monday and am concerned. I wonder if I should push for two additional weeks non-weight bearing after reading about this surgery. I have only left the house twice in five weeks because stairs and crutches are a bad combination. Overall, to wake up and find that someone did this to you without permission feels line a violation of sorts. I’ve had a difficult time with the idea that the doctor arbitrarily chose for me to go through this. My husband and I would have preferred time to research this type of surgery and alternatives before making a decision.

I’m a swimmer in my 50’s female and I too was surprised to wake up with the microfracturing procedure done what a shock! I am almost 6 months out and not anywhere near my physical abilities before surgery. And I can’t even swim my best competitive stroke- breaststroke. And on top of it all I’ve gained a significant amount of weight. I’m pretty much not the same person I was 6 months ago in every way. Very disappointed. I tried PT but it didn’t seem to help me. At this point I think it’s a fail but hopefully I will continue to see small improvements. Frustrating to Say the least.

I had microfracture surgery on October 15, 2020. I am a 56 year old Flight Attendant, very active and healthy. I went in for a simple meniscus repair and woke up in recovery and found out that the doctor had done microfracture surgery. I had never even heard of microfracture surgery, it was never even discussed. I was in a wheelchair for two months, crutches for a month, one crutch for a month, and I am now barely walking and it’s almost been six months since my surgery. For the first three months, I went to Physical Therapy three times a week and the fourth month I went to PT once a week. I stopped going to PT in my fifth month after surgery. I have seen my doctor several times and told him my knee hurts worse now than it ever did and he said it’s suppose to hurt. I am about to start my sixth month post surgery and my knee hurts so much, I have started walking with the assistance of a crutch. My family and friends are totally shocked as I use to be a very active person and now I can barely get around. I have not been able to go back to work since my surgery. Today, I called a new Orthopedic surgeon to get a second opinion. Before I had this surgery, I had a little bit of pain every once in a while, but now I have horrible pain almost every day. I’m angry that this Doctor decided to do this surgery without telling me about it. I hope and pray it gets better…..I have started riding my bicycle again and working out, but simple walking hurts.

I thought I was the only one. I went in to what I thought was a meniscus surgery. The hospital even sent me home with meniscus surgery paperwork. The very next day I’m walking. A week later, I go in to my doctors for a follow up snd asks, ‘where are your crutches.’ Nonchalantly says I’ll be on crutches for 6-8 weeks. What a shock!!! I was NoT ready for this. What hadn’t my doctor discussed this before surgery? A year and a half later, pain, every day. I’m an active person snd this surgery was not done on my consent and also was the worst thing that’s happened to me. DO NOT let your doctor do this surgery.

I’m a 65 year old male who has been running and playing sport all my life. Running has been off the agenda for a year but distance hiking and mountains are definitely there.

A year ago I was out running and felt real pain in my knee. My first ever knee issue. This deteriorated quickly and soon I was struggling to walk more than a mile or so and definitely struggled on stairs.

I had an MRI scan and it was suggested by Dr Chanakarn in Thailand that keyhole surgery would indicate the best treatment and the possibility of microfracture was explored. I had microfracture in the end.

Rehab has involved strengthening my quads and hamstring and my entire leg. I exercise daily without impact.

It is now six months since the operation and I can walk distances with no pain. I can climb mountains and walk up and down stairs. I am aware it is not as “easy’ as it used to be and my right knee is subconsciously favored but I can honestly say I am delighted so far. I can do all the things I now want to do as high impact is possibly a thing of the past. My only concern is longevity, how long will this last. I guess at my age 20 years will be about fine!! Maybe I am lucky but a good BMI, a healthy diet, regular exercise applied sensitively and I’m feeling great!

Same here ! At 54 yrs n karate player, woke up with surprise, I had a microfracture done. I thought there’s some hearing problem when my doc said TWO weeks non weight bearing. MRI show 6x8mm defect, but the repair is 1x1cm. I read about 6 weeks non weight bearing, not sure why mine is 2 weeks. Its been 8 weeks now, I can walk with slight limp, minmum weight bearing, unfortunately still cant squad, working on it