Patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy can benefit from participation in mild to moderate aerobic, resistance, and balance activities. But they must take precautions to ensure exercise is safe as well as effective, particularly with regard to the risk of foot ulceration.

Patients with diabetes and peripheral neuropathy can benefit from participation in mild to moderate aerobic, resistance, and balance activities. But they must take precautions to ensure exercise is safe as well as effective, particularly with regard to the risk of foot ulceration.

By Steven Morrison, PhD, and Sheri R. Colberg, PhD

Throbbing pain in the feet, a burning sensation in the hands, and a loss of sensation in the toes or fingers all can be symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, a condition that develops frequently as a long-term complication of diabetes and is caused by damage to the peripheral nerves. Peripheral pain or loss of sensation in the feet or hands is common in individuals with both types of diabetes and can occur in the absence of diabetes.1 The prevalence of neuropathy in people with diabetes is staggering, and as many as 60% to 70% of adults with diabetes exhibit signs of significant damage to their peripheral nerves.2 The most common form of peripheral neuropathy, distal symmetrical polyneuropathy, usually involves both small and large diameter nerve fibers and typically becomes symptomatic after a patient experiences many years of poorly controlled diabetes. Alternatively, it may even develop shortly after the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes if elevated blood glucose levels went undetected for years prior to diagnosis.3

Neuropathy and physical function

Peripheral neuropathy can cause problems with physical function for many reasons. While a loss of peripheral sensation is not by itself life threatening, the physical consequences of this damage can be quite profound. Sensory information about the body and from the environment are used in a variety of ways, allowing individuals to gain information about texture and temperature from objects we hold or touch, giving feedback (ie, pain and burning) when there is injury or damage to a body part, and also providing awareness of where the limbs and body are in space (ie, proprioception).

When the transmission of these different forms of sensory information is impaired, a person may have difficulty with a number of everyday tasks. For example, he or she may have difficulty holding a cup of coffee, lifting or carrying heavy objects, and judging the distance between obstacles when walking, which increases the likelihood of tripping and falling.

When the transmission of these different forms of sensory information is impaired, a person may have difficulty with a number of everyday tasks. For example, he or she may have difficulty holding a cup of coffee, lifting or carrying heavy objects, and judging the distance between obstacles when walking, which increases the likelihood of tripping and falling.

Alterations in temperature, pain perception, and impaired position sense also frequently lead to a loss of balance and postural control,4,5 especially in dimly lit conditions and when the eyes are closed. People with diminished sensation also may not experience the normal warning signs that indicate an injury to the feet or hands has occurred. As a result, a blister or repeated trauma may go unnoticed. Over time, painless injuries can lead to undetected ulcers, gangrene, and lower extremity amputations.6

A decline in nerve function can also lead to other profound changes, such as slower reactions and reflexes, a feeling of light-headedness or dizziness, general muscle weakness, tiredness or fatigue, and changes in walking ability and balance control.3,4,7 Limb weakness may result in difficulty climbing and descending stairs, getting up from a seated or supine position, holding objects, and raising the arms above the shoulders. The combination of slower reactions and muscle weakness may lead to an inability to catch oneself when tripped and so lead to more frequent falls.8,9 In the hands, loss of sensation can lead to impaired fine hand coordination, grasping, and force control10-12 —all of which can translate to difficulty with everyday tasks like opening jars, using utensils for eating, or turning keys.

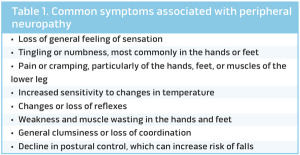

Table 1 lists some of the more common symptoms associated with peripheral neuropathy, most of which can, in many cases, lead to a decreased quality of life for the person experiencing them.

How can exercise help?

For persons with diabetes who exhibit a significant decline in sensory nerve function, the ultimate goal is to find an effective treatment that will reverse or prevent further peripheral nerve damage. Exercise is one intervention often prescribed as a somewhat effective treatment strategy for persons with nerve damage related to neuropathy. It is well known that physical activity per se is useful for all individuals, given that its benefits are widespread throughout the body, affecting all components of a person’s physiology, from cardiovascular function to respiratory, endocrine, and neuromuscular systems. This is particularly true for persons with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, in whom research has shown that maintaining a mild to moderate exercise training regimen can lead to improved sensory responses in the legs, and may help prevent the onset of peripheral neuropathy.13

Some researchers have speculated that the benefits for exercise may extend to the nerve fibers themselves, with a recent report stating that increased physical activity in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy can lead to increased nerve fiber branching and produce structural improvements in neural function.14 If nothing else, exercise participation can prevent worsening of the muscle strength and flexibility losses commonly experienced by those with both small and large nerve fiber damage.3 Thus, in addition to the more general improvements seen in physiological function, exercise has the potential to induce structural changes in the nervous system, which could also translate to functional benefits for everyday activities.

Some researchers have speculated that the benefits for exercise may extend to the nerve fibers themselves, with a recent report stating that increased physical activity in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy can lead to increased nerve fiber branching and produce structural improvements in neural function.14 If nothing else, exercise participation can prevent worsening of the muscle strength and flexibility losses commonly experienced by those with both small and large nerve fiber damage.3 Thus, in addition to the more general improvements seen in physiological function, exercise has the potential to induce structural changes in the nervous system, which could also translate to functional benefits for everyday activities.

For older adults, neuropathy can lead to dramatic declines in their ability to maintain an optimal level of balance, leading to changes in how well they are able to perform many locomotory activities of daily living, such as walking, standing up from a seated position, and climbing stairs. Persons with neuropathy tend to walk at a slower pace, taking shorter steps with a wider stance compared with healthy persons of a similar age.5,15,16 It seems reasonable to assume that these adaptive responses are related to diminished balance control, perceptions of increased risk of falling, or both. Individuals who have compromised balance or walking ability or who have a previous history of falling may also develop a “fear of falling”—a term used to describe an individual’s heightened perception of threats to their postural control when they move.17

Currently, it is estimated that close to 13 million (36%) of American adults older than 65 years are moderately fearful of suffering a fall.18 An unfortunate consequence of any decrease in balance and walking ability coupled with a fear of falling is the increased likelihood of suffering a fall in the future,19, 20 which can lead to further injury and curtailment of physical activity.

Fortunately, research suggests that exercise and training interventions for these individuals have some significant benefits. General improvements in overall falls risk, better balance and posture, and improved speed of reactions and walking function have all been reported following implementation of exercise and training programs for older adults with type 2 diabetes.8,9,21,22

Some of the benefits of low-impact balance exercise can be seen with very little training. When both healthy older persons and older adults with type 2 diabetes and mild to moderate peripheral neuropathy engaged in resistance and balance training done thrice-weekly for only six weeks, both groups showed improvements in balance, speed of reaction time, and falls risk, along with improved postural dynamics, illustrating that this intervention can lead to reasonably rapid improvements in function.8,9 Other research has shown that six months of weekly tai chi training can improve plantar sensation and balance in both healthy elderly adults and elderly adults with diabetes and large plantar sensation losses.23

Some of the benefits of low-impact balance exercise can be seen with very little training. When both healthy older persons and older adults with type 2 diabetes and mild to moderate peripheral neuropathy engaged in resistance and balance training done thrice-weekly for only six weeks, both groups showed improvements in balance, speed of reaction time, and falls risk, along with improved postural dynamics, illustrating that this intervention can lead to reasonably rapid improvements in function.8,9 Other research has shown that six months of weekly tai chi training can improve plantar sensation and balance in both healthy elderly adults and elderly adults with diabetes and large plantar sensation losses.23

Together, these results demonstrate that structured exercise can have widespread positive effects on physiological function for individuals with neuropathy. Thus, while the use of strength and balance training for older healthy adults at risk for falls has been a common practice, the implementation of similar training interventions for those older people with peripheral neuropathy can also have profound benefits.24 This approach has recently been endorsed by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA), which both recommended the use of strength and balance training for persons with neuropathy.25

Safety concerns and precautions

Engaging in weight-bearing physical activities can, unfortunately, be a double-edged sword for the person with peripheral neuropathy, since doing so may increase the risk of falls and foot problems, such as ulcers. Consequently, the general recommendation is that walking and many other locomotor activities should not be prescribed in isolation without considering the increased risk of plantar injury. Ideally, walking and balance exercises should be supplemented by partial or nonweight-bearing exercises to improve physical fitness in populations with diabetes that have peripheral neuropathy or are at high risk of developing the condition.26

Safety must be the prime consideration when recommending exercise to anyone with peripheral neuropathy. A series of specific recommendations for exercise for persons with peripheral neuropathy are shown in Table 2. Of importance is the inclusion of range-of-motion exercises, strengthening and balance activities, and a variety of other exercises that include walking and some optional lower impact activities such as cycling, swimming, other aquatic exercises, and chair exercises. In general, an individual with diabetic peripheral neuropathy and an unhealed foot ulcer should avoid or limit activities requiring significant weight bearing; however, such activities do not necessarily increase the risk of reulceration after complete healing.27,28

Another way to prevent problems is to make sure that individuals with diabetes are educated about proper foot care and the need for frequent foot examinations to prevent ulcers or catch them early before they become more severe. It is recommended that individuals undertake daily inspection of their feet, either by examining their feet themselves or by having someone else assist them. For example, a mirror can be placed on the floor and used to examine the bottoms of the feet for redness, discoloration, swelling, or other areas of trauma.29 Use of proper footwear (socks and shoes that minimize trauma) is also important for prevention of sores or ulcers: silica gel or air midsoles in shoes is recommended, along with polyester or polyester-blend (cotton-polyester) socks to prevent the formation of blisters and to keep feet dry.25 Patients do not necessarily have to wear diabetic footwear for exercise as long as their conventional athletic footwear meet these criteria.

In cases in which orthoses are used, individuals can insert these in athletic shoes in place of the customary sole inserts the shoes are sold with. Individuals with neuropathy and foot deformities may need custom footwear or orthotic inserts, in particular after healing of ulcers has occurred, to redistribute and reduce plantar foot pressures and to prevent reulceration.30-32 Table 3 includes some additional physical activity considerations for individuals with peripheral neuropathy, particularly individuals who are suffering from ulcerations and lower limb amputations.

In conclusion, the development of peripheral nerve damage is common in individuals with any type of diabetes. Peripheral neuropathy, with the associated decreases in sensation, carries with it an increased risk of falling and injury, along with greater discomfort associated with painful types of neuropathy during physical activity. Although physical activity cannot fully reverse the symptoms of

peripheral neuropathy, it may improve nerve function and can prevent further loss of physical function related to the waning muscle strength and decreased flexibility commonly experienced by individuals with neuropathy.

All individuals with peripheral neuropathy can benefit from regular participation in mild to moderate aerobic, resistance, and balance activities, but they must take precautions to ensure exercise is safe and effective.

Steven Morrison, PhD, is director of research and an endowed professor of physical therapy in the School of Physical Therapy and Athletic Training at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, VA. Sheri R. Colberg, PhD, is a professor of exercise science in the Human Movement Sciences Department at Old Dominion University.

- Smith AG, Singleton JR. Impaired glucose tolerance and neuropathy. Neurologist 2008;14(1):23-29.

- Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care 2012;35(12):2650-2664.

- Casellini CM, Vinik AI. Clinical manifestations and current treatment options for diabetic neuropathies. Endocr Pract 2007;13(5):550-566.

- Richardson JK, Hurvitz EA. Peripheral neuropathy: a true risk factor for falls. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1995;50A(4):M211-M215.

- Richardson JK, Thies SB, DeMott TK, Ashton-Miller JA. Gait analysis in a challenging environment differentiates between fallers and nonfallers among older patients with peripheral neuropathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005;86(8):1539-1544.

- Alvarsson A, Sandgren B, Wendel C. A retrospective analysis of amputation rates in diabetic patients: can lower extremity amputations be further prevented? Cardiovasc Diabetol 2012;11(1):18.

- Crews RT, Yalla SV, Fleischer AE, Wu SC. A growing troubling triad: diabetes, aging, and falls. J Aging Res 2013;2013:342650.

- Morrison S, Colberg SR, Mariano M, et al. Balance training reduces falls risk in older individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33(4):748-750.

- Morrison S, Colberg SR, Parson HK, Vinik AI. Relation between risk of falling and postural sway complexity in diabetes. Gait Posture 2012;35(4):662-668.

- Dixit S, Maiya A, Shastry B. Effect of aerobic exercise on quality of life in population with diabetic peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetes: a single blind, randomized controlled trial. Qual Life Res 2014;23(5):1629-1640.

- Ochoa N, Gorniak SL. Changes in sensory function and force production in adults with type II diabetes. Muscle Nerve 2014 Apr 7 [Epub ahead of print]

- Resnick HE, Stansberry KB, Harris TB, et al. Diabetes, peripheral neuropathy, and old age disability. Muscle Nerve 2002;25(1):43-50.

- Balducci S, Iacobellis G, Parisi L, et al. Exercise training can modify the natural history of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications 2006;20(4):216-223.

- Kluding PM, Pasnoor M, Singh R, et al. The effect of exercise on neuropathic symptoms, nerve function, and cutaneous innervation in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications 2012;26(5):424-429.

- Allet L, Armand S, De Bie RA, et al. Clinical factors associated with gait alterations in diabetic patients. Diabet Med 2009;26(10):1003-1009.

- Allet L, Armand S, Golay A, e al. Gait characteristics of diabetic patients: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2008;24(3):173-191.

- Ko SU, Stenholm S, Chia CW, et al. Gait pattern alterations in older adults associated with type 2 diabetes in the absence of peripheral neuropathy—Results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Gait Posture 2011;34(4):548-552.

- Boyd R, Stevens JA. Falls and fear of falling: burden, beliefs and behaviours. Age Ageing 2009;38(4):423-428.

- Close JCT, Lord SL, Menz HB, Sherrington C. What is the role of falls? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2005;19(6):913-935.

- Vellas BJ, Wayne SJ, Romero LJ, et al. Fear of falling and restriction of mobility in elderly fallers. Age Ageing 1997;26(3):189-193.

- Allet L, Armand S, de Bie R, et al. The gait and balance of patients with diabetes can be improved: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2010;53(3):458-466.

- Morrison S, Colberg SR, Parson HK, Vinik AI. Exercise improves gait, reaction time and postural stability in older adults with type 2 diabetes and neuropathy. J Diabetes Complications 2014;28(5):715-722.

- Richerson S, Rosendale K. Does tai chi improve plantar sensory ability? A pilot study. Diabetes Technol Ther 2007;9(3):276-86.

- Kruse RL, LeMaster JW, Madsen RW. Fall and balance outcomes after an intervention to promote leg strength, balance, and walking in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: “Feet First” randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2010;90(11):1568-1579.

- Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: The American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care 2010;33(12):e147-e167.

- Kanade RV, van Deursen RWM, Harding K, Price P. Walking performance in people with diabetic neuropathy: benefits and threats. Diabetologia 2006;49(8):1747-1754.

- LeMaster J, Reiber GE, Smith DG, et al. Daily weight-bearing activity does not increase the risk of diabetic foot ulcers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35(7):1093-1099.

- LeMaster JW, Mueller MJ, Reiber GE, et al. Effect of weight-bearing activity on foot ulcer incidence in people with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: feet first randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2008;88(11):1385-1398.

- Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA 2005;293(2):217-228.

- Bus SA, Valk GD, van Deursen RW, et al. The effectiveness of footwear and offloading interventions to prevent and heal foot ulcers and reduce plantar pressure in diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2008;24(S1):S162-S180.

- Rizzo L, Tedeschi A, Fallani E, et al. Custom-made orthosis and shoes in a structured follow-up program reduces the incidence of neuropathic ulcers in high-risk diabetic foot patients. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2012;11(1):59-64.

- Ulbrecht JS, Hurley T, Mauger DT, Cavanagh PR. Prevention of recurrent foot ulcers with plantar pressure–based in-shoe orthoses: The CareFUL prevention multicenter randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2014;37(7):1982-1989.