End-stage arthritis of the ankle joint affects more than 50,000 people in the US. When conservative treatments do not provide enough relief, surgical options should be considered. Patient selection is key when choosing between ankle arthrodesis (fusion) and total ankle arthroplasty (replacement).

By Vicki Foerster, MD, MSc

In end-stage ankle arthritis, joint cartilage has worn away and pain occurs as bone rubs against bone. Although less common than arthritis of the hip or knee, the pain and disability of end-stage ankle arthritis affect patients as much as severely disabling physical conditions such as end-stage hip arthritis, end-stage kidney disease, and congestive heart failure.1-4

An estimated 50,000 people in the USA have end-stage ankle arthritis.5 In up to 80% of cases, the condition is posttraumatic,6 with the 3 most common traumatic causes being rotational ankle fractures (37%), recurrent ankle instability (15%), and single sprain with continued pain (14%).7 An end-stage ankle can also be caused by other kinds of arthritis, including rheumatoid, hemophilic, septic, neuropathic, and idiopathic, as well as osteonecrosis and gout.8 Because many cases occur posttrauma, end-stage ankle arthritis is associated with a younger population than hip and knee arthritis, affecting people in their 5th and 6th decades of life—compared to surgery for hip and knee arthritis, which is performed mostly in the 7th and 8th decades.6

- Compressive forces on the main ankle joint (the tibiotalar joint) can be 4 times body weight during normal walking.

- Serving as a shock absorber for the body, an ankle has only a small surface area

to bear the body’s weight and is injured more often than any other joint. - For surgeons, the ankle is a dif cult joint, due to its small size and its complexity; once injured, it is hard to repair, especially in older people.

Treatment options

Conservative treatment

Conservative treatment for end-stage ankle arthritis includes activity modification, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, braces, physical therapy, shoewear modification, and ankle steroid injection.9-11 However, if these treatments do not provide enough relief, current surgical options are joint fusion (ankle arthrodesis [AA]) and joint replacement (total ankle arthroplasty [TAA]).3,8,12

Ankle arthrodesis

AA uses screws, with or without plates and bone grafting, to fuse the articulating tibiotalar joint into a solid immovable bone. In some cases, the procedure may be carried out laparoscopically.13 Considered the gold standard of surgery to reduce pain for end-stage ankle arthritis,6,14,15 the procedure can lead to decreased ankle motion, altered gait, accelerated arthritis in surrounding joints, and nonunion.3,8,12 According to Peter G. Mangone, MD, foot and ankle orthopedic surgeon in Asheville, NC, and Co-Director of the EmergeOrtho: Blue Ridge Division Foot and Ankle Center, AA continues to be the treatment of choice for a number of patients (see “Patient selection,” below, for details). Likewise, Joel Morash, MD, PhD, a surgeon specializing in reconstructive foot and ankle surgery at Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, described AA as a useful procedure that should not be considered inferior to TAA, noting that some patients cope well postoperatively without significant gait changes.

Total ankle arthroplasty

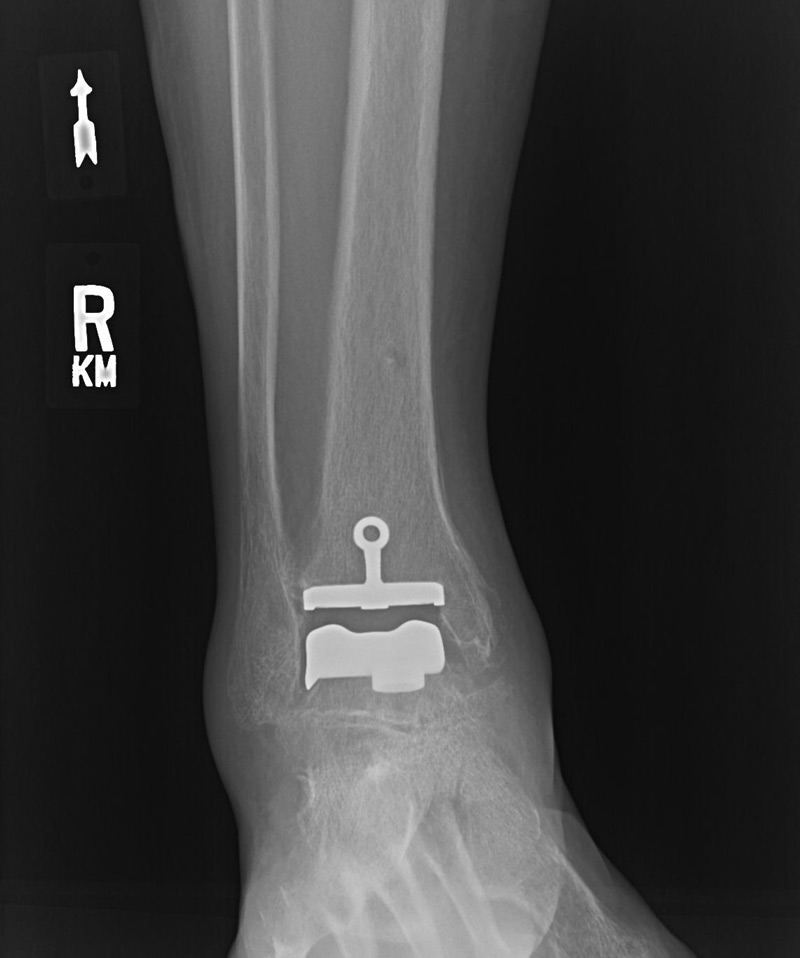

TAA uses a 2-part or 3-part implant to resurface the ends of the tibia and the talus with metal components and a synthetic piece positioned between them, allowing joint movement. TAA offers greater ankle range of movement than AA and can therefore improve gait, decrease stress on other joints, and potentially lead to less arthritis in surrounding joints; however, complications include implant loosening, ankle instability, osteolysis, infection, and a need for reoperation.3,8,12

In the 1970s, TAA was developed as an alternative to AA; although first-generation TAA implants had an unacceptably high complication rate, recent (3rd- and 4th-generation) TAA designs have led to better outcomes.5,8,14-16 Supporters of TAA note that, although long-term survivorship of the newest implants (10 to 15 years and longer) is unknown (some have been used for 5 years or less), current designs and approaches suggest that TAA can match the favorable outcomes of AA and allow preservation of ankle motion, at least in the short term.8,12,15

As TAA surgical technique and implant design have gained sophistication, the number of TAAs performed in the United States has risen—although the rate of AA continues to be about double that of AA.17, 18 Some specialist surgeons, such as W. Hodges Davis, MD, (foot and ankle surgeon and medical director, OrthoCarolina Foot and Ankle Institute, Charlotte, NC) and Steven Haddad, MD, (foot and ankle surgeon, Illinois Bone and Joint Institute, Glenview, Il, and Past President, American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society) have seen their practices shift dramatically, with the rate of TAA significantly outweighing the rate of AA.

TAA prostheses available in the USA (FDA Class II medical devices)

Although more than 20 TAA devices have been available worldwide, only a subset has been approved as FDA Class II medical devices for use in the United States, including:10,19

- Agility® and Mobility® (DePuy Orthopaedics)

- Cadence® Total Ankle System (Integra LifeSciences)

- INFINITY®, INBONE®, and INVISION® (Wright Medical Group)

- Salto Talaris® and Salto Talaris XT™ (Tornier US)

- STAR (Scandinavian Total Ankle Replacement) (Stryker)

- Trabecular Metal™ Total Ankle (Zimmer) – lateral approach

- Vantage® Total Ankle Mobile Bearing System (Exactech, Inc.)

This list includes devices designed specifically for revisions of primary TAAs. According to Mangone, the implant landscape is always changing, as there are constant improvements in implant design and growing experience as to which implants work best in which cases. Davis noted that, although the newest devices are limited to a short period of experience, their design is built on predecessor devices that have shown satisfactory outcomes and longevity.

Recovery periods for both procedures

Postoperative care for AA involves 10 to 12 weeks in a cast, whereas a TAA requires 3 to 6 weeks, followed by physical therapy.20 Advice from one university is that both AA and TAA allow normal daily activities in 3 to 4 months, with full recovery for AA in 4 to 9 months and TAA in 6 to 12 months, depending on the severity of the preoperative condition and surgical complexity.13,21

Published comparisons of the two surgical alternatives

iStockphoto.com 493952349

Chicago researchers compared AA and TAA outcomes published between 2006 and 2016 because they were concerned about lack of consensus about end-stage ankle arthritis treatment.8 They pooled results from 6 AA case series and 5 TAA case series (limited to those using 3rd-generation implants approved for marketing in the United States) and also assessed 10 studies comparing the 2 procedures. In all, data for more than 4000 ankles were used. From the pooled case series, AA had a higher complication rate than TAA (27% and 20%, respectively) but a lower revision reoperation rate (5% and 8%, respectively). The most frequently reported AA complications were wound complication, nonunion, deep infection, and fracture; whereas for TAA, the main complications were device loosening, wound complication, fracture, and deep infection. Ultimately, the authors concluded that decisions should be made on an individual patient basis because significant advantages of one procedure over the other were unclear.

A meta-analysis of 10 AA–TAA comparative studies was published by researchers the republic of Korea.22 They concluded that AA and TAA led to similar clinical outcomes, but that incidence rates of reoperation and major surgical complications were significantly increased in TAA—in particular, wound problems, perioperative fracture, and nerve injury. Other published reports of complications are detailed in the table.

Conversion from one procedure to the other

The longevity of TAA is less than that of hip or knee replacements, despite advances in techniques and implant design.6 Micro-motion of the implants may lead to lack of bone-implant integration; furthermore, even slight errors in positioning an implant can lead to failure.25 Ideally, a TAA can be revised but, if not, AA is the main option. According to Morash, converting TAA to AA is complicated; much depends on the state of the bones when the prosthesis pieces are removed. AA for failed TAA has a higher nonunion rate; patients must be aware that complications from these procedures may lead to amputation.

A systematic review of 16 studies published from 1982 to 2012 (193 patients total) analyzed AA after failed TAA and found that most patients needed AA surgery due to TAA component loosening, usually of the talar component.18 The overall surgical complication rate was 18%, with a nonunion rate of 11%. Patient satisfaction rates were generally high.

Morash noted that it is very important when converting an AA to TAA (called a fusion takedown) to ensure that the patient understands that the main goal of surgery is pain reduction, as range-of-motion will likely remain limited because the fused joint is accustomed to years of tissue restriction with the fusion in place. Conversion of AA to TAA is technically demanding and considered by some to be controversial.26,27 Davis pointed out the lack of published experience on the AA to TAA procedure means that long-term outcomes are unknown.

A Utah study of 18 patients who received TAA after AA due to nonunion or mal-union reported that pain and function improved; however, functional outcomes, including postoperative range of motion, were lower than those reported for primary TAA, and complications were frequent.27 Another study of 23 patients from North Carolina reported pain relief and improved function in most patients.26 The authors noted that patients who undergo TAA after AA often need additional procedures, such as prophylactic malleolar fixation. In an additional small study of 5 patients who received TKA due to symptomatic nonunion after AA, 4 were very satisfied or satisfied after a mean 21 months of follow-up.28

Patient selection

Choice of treatment depends on a patient’s age, range of motion, level of activity, joint alignment, and expectations.11,15,20 Foot and ankle orthopedic surgeons Magone and Morash noted how important it is to 1) select the right patients for each procedure, and 2) ensure that patients (and providers caring for them) have a realistic understanding of what the surgical outcomes will be.

AA has traditionally been recommended for younger patients (traditionally, younger than 65 years), the very active, and those with significant ankle damage.21 Thinking is evolving, with expanded TAA indications including younger patients (35 or 40 to 50 years of age) and more significant ankle deformities.6,15 A Canadian retrospective database study of nearly 400 ankle procedures found that patients treated with AA were younger (mean age, 55 years) than TAA patients, more likely to be diabetic and smokers, and less likely to have inflammatory arthritis.23

Additional AA indications include:1,8-10

- arthritis secondary to trauma or neuromuscular disease

- unilateral ankle arthritis (ankle range of motion less than 10°)

- absence of arthritis in adjacent joints

- severe ankle instability (coronal deformity greater than 15°)

- history of joint infection or serious medical problems, including vascular issues in the area

- ankles that are severely deformed

- inadequate or absent leg muscle function or inadequate soft tissue

- lack of protective sensation or clear neuropathy patients with diabetes (due to the high likelihood of distal extremity neuropathy).

Patient expectations

As the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society’s Past President Haddad points out, patients must understand that an AA that fuses correctly is the only permanent solution to eliminating pain, although some will need future procedures to fuse adjacent joints that become arthritic due to increased stress. In contrast, the need for future surgery is very likely for those with a TAA, due to the realities of device longevity, particularly in younger people. Also, providers caring for patients with end-stage ankle arthritis who undergo surgery must have realistic goals. The main focus is to decrease pain and increase functionality somewhat, not to return to premorbidity function; however, patients often have realistic expectations because their presurgical function was so limiting for them. Patients must learn to take good care of their implants by avoiding aggressive sports and sudden-impact activities (e.g., basketball, skydiving, and horseback riding) and limiting themselves to activities in which ankle movement is controlled (e.g., hiking, golfing, cycling, and swimming).

According to the orthopedic surgeons interviewed for this article, AA should not be seen as an inferior option, as it might, in fact, be the best option for many people. Magone said that he may initially uses AA in people in the 35 to 40-year-old range, then convert to a TAA when pain in adjacent joints surfaces some years later. Converting to TAA surgery can then avoid fusion of other ankle joints. The approach depends on the patient’s needs, activities, expectations, and foot flexibility.

Cost considerations

A 2004 decision model was favorable toward TAA versus AA, with a calculated gain of 0.52 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), at a cost of $9600; 10-year device survival was assumed.29 A comparison in 2011 used a Markov decision analysis for a hypothetical 60-year-old cohort and was again favorable to TAA, reporting that TAA cost $20,200 more than AA but resulted in 1.7 additional QALYs, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $11,800/QALY gained.2 The authors concluded that, despite more costly implants, TAA can be a cost-effective alternative to AA.2

A 2015 Canadian analysis looked at teaching hospital costs (in 2006 Canadian dollars) for various alternatives, including operating room time, hospital stay, surgeon billing, and equipment used.4 The analysis concluded that AA is a less expensive and preferable alternative for some patient groups (e.g., young and active, diabetic, and with severe deformity) at $5500; however, TAA should not be denied based on device cost alone ($6420 in this analysis, compared to $1200 for AA) because the total in-hospital procedure cost of $13,500 was comparable to that of total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty. Also, TAA mean operating room time was longer, but mean hospital stay was shorter for the ankle procedures, compared with total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty.

iStockphoto.com 229583662

Recent trends

There are ongoing efforts to develop and market a satisfactory TAA device due to the drawbacks of AA,4 and the number of TAAs being performed is increasing as outcomes improve with newer bone-sparing implant designs and improved surgical techniques.9,25 In particular, early TAA devices have been replaced by 3rd- and 4th-generation devices made of advanced metal alloy and plastic that are engineered to interact with each other to maximize mobility and flexibility.

Davis summarized his advice by saying that AA remains the optimal choice for some patients (e.g., those with arthritis isolated to the tibiotalar joint), but that this number is shrinking as new research shows the benefits of TAA with increasing implant and surgical sophistication. Overall, TAA advocates believe that, as TAA implants gain sophistication and spare more bone, and surgical techniques advance, the populations suited for TAA will continue to grow, although AA will likely always be the best choice for certain patient groups.

Dr. Foerster is a freelance medical writer in Oxford Station, Ontario, Canada.

- Morash J, Walton DM, Glazebrook M. Ankle arthrodesis versus total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Clin. 2017;22(2):251-266.

- Courville XF, Hecht PJ, Tosteson AN. Is total ankle arthroplasty a cost-effective alternative to ankle fusion? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(6):1721-1727.

- Baumhauer JF. Ankle arthrodesis versus ankle replacement for ankle arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(8):2439-2442.

- Younger AS, MacLean S, Daniels TR, et al. Initial hospital related cost comparison of total ankle replacement and ankle fusion with hip and knee joint replacement. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(3):253-257.

- Pianin E. Ankle replacement was once disparaged as borderline quackery. No longer. The Washington Post. October 17, 2017.www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/ankle-replacement-was-once-disparaged-as-borderline-quackery-no-longer/2017/10/20/fb5db206-9e2a-11e7-8ea1-ed975285475e_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.6bf802428903. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Dujela MD, DeCarbo WT, Espinosa N, Weber JS, Larson DR, Hyer CF. Chapter 30: Evolution of total ankle replacement within the US. In: Update 2017. Decatur, GA: The Podiatry Institute; 2017:139-149. www.podiatryinstitute.com/pdfs/Update_2017/Chapter30_final.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Weatherall JM, Mroczek K, McLaurin T, Ding B, Tejwani N. Post-traumatic ankle arthritis. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 2013;71(1):104-112.

- Lawton CD, Butler BA, Dekker RG 2nd, Prescott A, Kadakia AR. Total ankle arthroplasty versus ankle arthrodesis-a comparison of outcomes over the last decade. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12(1):76-85.

- American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society. FootCareMD: Total ankle arthroplasty. www.aofas.org/footcaremd/treatments/Pages/Total-Ankle-Arthroplasty.aspx. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Centers for Advanced Orthopedics. Ankle arthritis and total ankle arthroplasty (replacement). www.footankledc.com/specialties/total-ankle-replacement. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Saito GH, Sanders AE, de Cesar Netto C, et al. Short-term complications, reoperations, and radiographic outcomes of a new fixed-bearing total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2018:1071100718764107. [Epub ahead of print]

- Odum SM, Van Doren BA, Anderson RB, Davis WH. In-hospital complications following ankle arthrodesis versus ankle arthroplasty: a matched cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(17):1469-1475.

- Emory Healthcare. Ankle arthrodesis (fusion). www.emoryhealthcare.org/orthopedics/ankle-fusion.html?_ga=2.79960791.1791773472.1524860863-1841104690.1524860863. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Pappas MJ, Buechel FF. Failure modes of current total ankle replacement systems. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2013;30(2):123-143.

- Hsu AR, Haddad SL. Will total ankle arthroplasty become the new standard for end-stage ankle arthritis? Orthopedics. 2014;37(4):221-223.

- Pangrazzi GJ, Baker EA, Shaheen PJ, Okeagu CN, Fortin PT. Single-surgeon experience and complications of a fixed-bearing total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(1):46-58.

- Terrell RD, Montgomery SR, Pannell WC, et al. Comparison of practice patterns in total ankle replacement and ankle fusion in the United States. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(11):1486-1492.

- Gross C, Erickson BJ, Adams SB, Parekh SG. Ankle arthrodesis after failed total ankle replacement: a systematic review of the literature. Foot Ankle Spec. 2015;8(2):143-151.

- Coetzee JC, Deorio JK. Total ankle replacement systems available in the United States. Instr Course Lect. 2010;59:367-374.

- Bowman KD. Ankle fusion or ankle replacement? Choosing the right ankle surgery. Duke Health Blog. November 1, 2016 www.dukehealth.org/blog/ankle-fusion-or-ankle-replacement. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Emory Healthcare. Total ankle replacement surgery. www.emoryhealthcare.org/orthopedics/ankle-replacement.html. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Kim HJ, Suh DH, Yang JH, et al. Total ankle arthroplasty versus ankle arthrodesis for the treatment of end-stage ankle arthritis: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Int Orthop. 2017;41(1):101-109.

- Daniels TR, Younger AS, Penner M, et al. Intermediate-term results of total ankle replacement and ankle arthrodesis: a COFAS multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(2):135-142.

- Stavrakis AI, SooHoo NF. Trends in complication rates following ankle arthrodesis and total ankle replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(17):1453-1458.

- Sopher RS, Amis AA, Calder JD, Jeffers JRT. Total ankle replacement design and positioning affect implant-bone micromotion and bone strains. Med Eng Phys. 2017;42:80-90.

- Pellegrini MJ, Schiff AP, Adams SB Jr, et al. Conversion of tibiotalar arthrodesis to total ankle arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(24):2004-2013.

- Preis M, Bailey T, Marchand LS, Barg A. Can a three-component prosthesis be used for conversion of painful ankle arthrodesis to total ankle replacement? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(9):2283-2294.

- Huntington WP, Davis WH, Anderson R. Total ankle arthroplasty for the treatment of symptomatic nonunion following tibiotalar fusion. Foot Ankle Spec. 2016;9(4):330-335.

- SooHoo NF, Kominski G. Cost-effectiveness analysis of total ankle arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(11):2446-2455.