By Tricia Hubbard-Turner, Michael J. Turner, Chris Burcal, Kyeongtak Song, and Erik A. Wikstrom

Despite an immense amount of research examining the causes and treatment of ankle sprains and chronic ankle instability (CAI), ankle sprains remain the most common musculoskeletal injury. The first consequence of an initial ankle sprain is the development of CAI. With upwards of 70% of patients who sprain their ankle going on to develop CAI. The second consequence is the development of post-traumatic ankle osteoarthritis. Ankle instability accounts for 80% of post-traumatic ankle osteoarthritis cases. Along with this data, we know that approximately 50% of patients that sprain their ankle never seek treatment, so some of this data may be underestimated by the lack of patients seeking treatment and reporting injury. Even with the high percentage of disability and long term consequences to an ankle sprain, it is often thought of as an inconsequential injury. More recent evidence has started to demonstrate the impact an ankle sprain may have on regular physical activity patterns, and early results point to ankle sprains being a bigger public health burden than traditionally given credit for, and thus needs to be treated as such.

One of the bigger areas of research in regards to consequences of ankle sprains and CAI development is subjective function via patient reported outcomes. When examining the research, it has consistently demonstrated individuals with CAI score significantly less on subjective self-report scales…

The purpose of this study is to examine the physical activity levels before and one year after an initial acute lateral ankle sprain (LAS).

Materials and Methods

Participants: Twenty college students (7 males and 13 females, age = 21.7 ± 2.7 yr, mass = 79.4 ± 18.1 kg, ht = 173.2 ± 9.5 cm) with an initial acute LAS and twenty healthy college students (7 males and 13 females, age = 20.4 ± 2.9 yr, mass = 80.6 ± 22.3 kg, ht = 172.4 ± 8.7 cm) participated in the study. For those with an acute LAS the following criteria had to be met: 1) Be between the ages of 16 and 50, 2) Have a first time lateral ankle sprain or first repetition of a lateral ankle sprain more than 1-year after the last sprain, and 3) Have the lateral ankle sprain occur within the past 72-hours. Exclusion criteria for the acute LAS group included: Chronic ankle instability in the involved ankle, a previous history of ankle surgery, fractures of the foot or ankle suffered at the same time as the lateral ankle sprain, or a condition known to affect pain and/or balance.

Inclusion criteria for healthy controls was the same as the acute LAS group with exception of no acute LAS. Additionally, control participants must be within ± 10% of an ankle sprain participant’s age, height, weight, physical activity level, and be of the same sex. Exclusion criteria for the control group was the same as the acute LAS group.

Procedures: After reading through and providing informed consent, all participants filled out three questionnaires—the foot and ankle ability measure (FAAM), the international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) short form, and the NASA physical activity scale. …One year after initial enrollment in the study all participants returned to complete post-data collection.

Statistical analysis: All subject demographic and injury related data was analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) between groups (LAS, Healthy). A two-way ANOVA (group X time) was used to determine any differences in the FAAM, the questions on the IPAQ, and the NASA physical activity score. An alpha-level of P < 0.05 was used to determine significant effects for each analysis.

Results

There were no significant differences in demographic data between the groups.

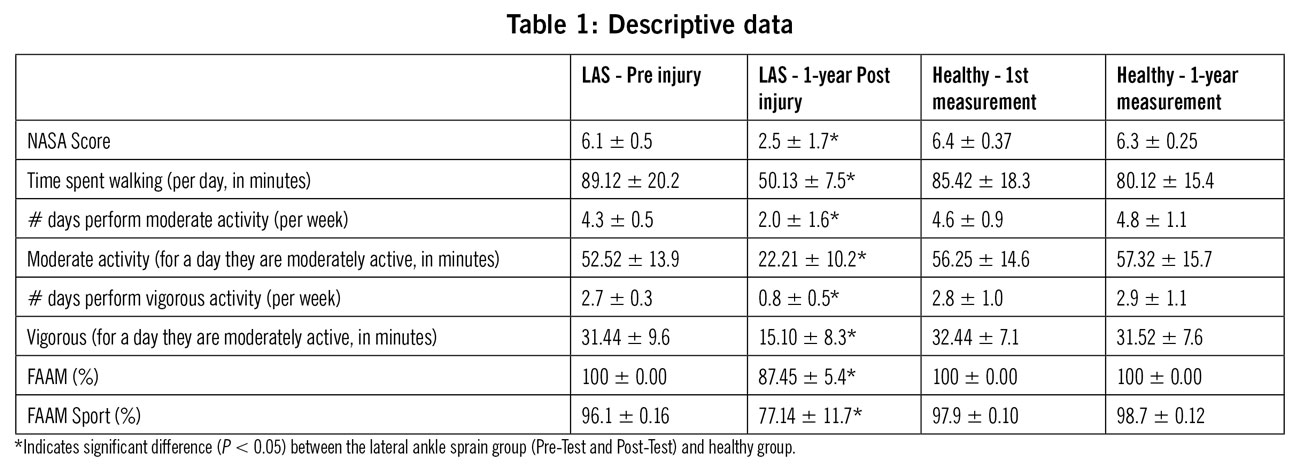

Means and standard deviations of the primary outcome measures are presented in the Table. There were no significant interactions for the FAAM (P = 0.10) or FAAM sport

(P = 0.45). There was a significant difference between groups. Participants in the healthy group scored significantly higher on the FAAM (P = 0.04) and the FAAM sport (P = 0.01) at the 1-year measurement compared to the LAS group. There was a significant interaction

(P = 0.001) for the NASA physical activity scale. Participants in the LAS group scored significantly less at the 1-year mark compared to their pre-injury levels (P = 0.001), and significantly less (P = 0.02) than the healthy group at the 1-year mark.

There were numerous significant interactions for the IPAQ physical activity questionnaire. The LAS participants scored significantly less on “average time spent performing vigorous physical activity” (P = 0.04) and “average time spent performing moderate physical activity” (P = 0.02) one year after injury compared to before the LAS and compared to the healthy group. Participants with a LAS also spent significantly less time during an average day walking (P = 0.01) and had significantly less days per week where they pursued vigorous activity (P = 0.02) or moderate activity

(P = 0.04) one year after their sprain compared to before the injury occurred and compared to the control group.

Discussion

The participants with the acute LAS scored significantly lower on NASA physical activity scale at the 1-year mark compared to their pre-injury physical activity levels and the activity levels of the healthy matched control group. The acute LAS group also scored significantly lower on the subjective function (FAAM and FAAM sport) scales. The decreased self-reported physical activity levels and subjective function is a concern. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommends adults get at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week. This can be met through 30-60 minutes of moderate intensity exercise (5 days per week) or 20- 60 minutes of vigorous – intensity exercise (3 days per week). The healthy participants in the study met the ACSM physical standards, and the acute LAS group met the standards before injury. However, 1-year after the acute LAS, participants fell below the physical activity guidelines. This is a significant public health concern that could result in physiological and financial concerns for these individuals in the near future.

Conclusion

Based on the current study, participants who sustained an initial acute LAS had significantly decreased physical activity levels 1-year after the injury compared to pre-injury levels and a healthy matched control group. Additionally, participants with an acute LAS had significantly decreased subjective function 1-year after the sprain relative to a healthy matched control group.

This article has been excerpted from “Decreased Self Report Physical Activity One Year after an Acute Ankle Sprain” by the same authors, which appeared in the Journal of Musculoskeletal Disorders and Treatment; 2018;4:062. References have been removed for brevity. Use is per the Creative Commons Distribution 4.0 International License. To read the full article, go to

https://www.clinmedjournals.org/articles/jmdt/journal-of-musculoskeletal-disorders-and-treatment-jmdt-4-062.php?jid=jmdt