istockphoto.com #32705

The American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons’ revised guidelines for heel pain treatment reflect lower extremity healthcare’s increasing focus on evidence-based medicine, including hundreds of references as well as helpful diagrams. But evidence has its limitations, and clinical experience is still essential to the therapeutic process.

by Cary Groner

New practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of heel pain, published on April 30 by the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons (ACFAS), continued the trend of basing treatment recommendations on evidence-based medicine.1 But the guidelines also provoked controversy among those most likely to rely on them for clinical decision making.

Heel pain—most commonly plantar fasciitis—is a serious matter for podiatrists, physical therapists, and other lower extremity clinicians. Roughly two million Americans are affected by it each year, and 10% of people experience chronic heel pain at some point in their lives.2

Despite the condition’s prevalence, practitioners disagree about the best treatments for it. Some of this has to do with scope of practice; physical therapists can’t give cortisone injections or perform surgery, of course, and podiatrists are usually less familiar with physical therapy approaches than with the techniques in which they’ve been trained. Some clinicians dismiss the relevance of orthoses, while others consider them the most crucial aspect of treatment. Certain practitioners feel that surgery is inappropriate for fasciitis, while others rely on it to an extent that their colleagues sometimes consider troubling.

istockphoto.com #9908371

Of course, the whole point of guidelines is to delineate the evidence for different approaches and help all practitioners make better decisions. And although there is significant confluence of ideas about best practices, the differences can be telling. The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) published its own set of heel pain guidelines in 2008 and provided significant evidence for its recommendations.3 And although the APTA recommendations agree in many respects with the ACFAS guidelines, the two documents also diverge in important ways.

Both organizations rank evidence and make recommendations based on the same template, though they differ in the details. Evidence is graded from Level I (the highest, based on randomized controlled trials) to Level IV or V (expert opinion). Grades of recommendation range from grade A (strong evidence, based on Level I or II studies) to grade F (in the case of the APTA guidelines) or grade I (in the ACFAS guidelines, “I” signifies “insufficient evidence to make a recommendation”).

The Word from ACFAS

The new ACFAS guidelines, which evolved from a previous version in 2001,4 classify heel pain in several categories and provide both text and graphic pathways for diagnosing, evaluating, and treating it. The clinician’s first step is to determine the cause of the problem, whether it be neurologic, arthritic, traumatic, or mechanical. This last etiology, which typically presents as plantar heel pain, is the most common.

“What’s really new in these guidelines is they are not just opinion-based; we’ve tried to look at evidence-based medicine and give treatment recommendations based on that,” said James Thomas, DPM, FACFAS, the lead author of the ACFAS guidelines.

istockphoto.com #6889503

Thomas, an associate professor in the department of orthopedics at West Virginia University in Morgantown, noted other improvements over the previous version.

“Newer technology and treatments are available now, such as radiofrequency coblation of the plantar fascia, though at this point it rates only a ‘C’ because it’s so new we don’t have the numbers to support it,” he said. “We will probably see that [literature] grow over the next few years.”

The new guidelines also note a shift in terminology.

“While ‘fasciitis’ describes the most common cause of heel pain, MRI studies are showing us that it is not just a matter of inflammation,” Thomas said. “There are degenerative changes in the fascia which are better described as ‘fasciosis.’ Practitioners recognize this and are starting to use the new term.”

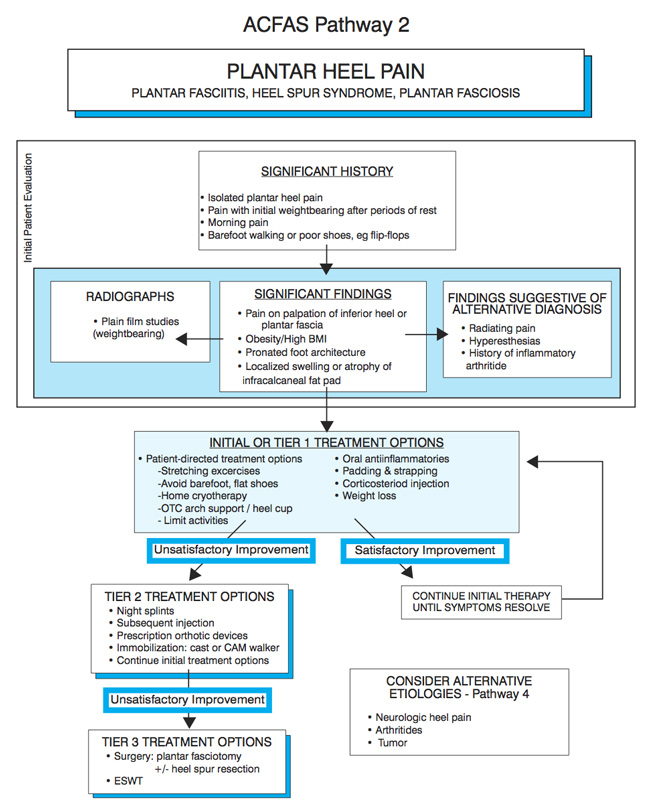

Thomas also pointed out the document’s flowcharts, which provide a succinct visual presentation of the decision trees in the text. In Pathway 2, “Plantar Heel Pain,” for example, clinicians are guided through taking the history (e.g., pain in the morning or after periods of rest); through significant findings (radiographs, pain on palpation, obesity, pronated foot architecture, and the like); through initial treatment options (e.g. stretching, over the counter insoles, cortisone injection, activity limitation, padding, and strapping); and finally to second and third-tier treatments that include night splints, prescription orthoses, repeated injections, and surgery.

Controversy

Some of these recommendations have stirred the pot of controversy, however. For example, corticosteroid injections are given an evidence grade of B in the guidelines’ text and listed as an initial treatment option; by contrast, physical therapy is not listed in any of the protocol’s three tiers (physical therapy received a grade of “I”—insufficient evidence to recommend—from ACFAS).

“I am strongly against cortisone shots as a first intervention,” said Michael Gross, PT, PhD, a professor of physical therapy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “They don’t address a single issue that gave the person the problem. Fasciitis is caused by tensile stress from the foot undergoing three-point bending, exacerbated by factors such as weight gain or increases in activity. An injection compromises tissue that is already weak, and it reduces pain that is the only thing telling the patient that something’s wrong. As a result, they’re likely to go out and hurt the tissue more, but they won’t know that until the analgesic wears off, at which point they’re in worse condition than they were originally.”

It’s not only physical therapists who object to this treatment approach.

“I would take exception to corticosteroids being in Tier 1, for a first visit,” said James Clough, DPM, who practices in Great Falls, MT. “There are people who come in with such severe pain that they can’t walk, and maybe there I would occasionally give an injection. But 95% of patients never need that. You’re running the risk of injuring Baxter’s nerve and creating a neuritis, and corticosteroids delay the healing process. Also, some studies have suggested the method of injection is more important than what is actually injected.”

Thomas acknowledged that clinical judgment should be a key factor in such decisions.

“With clinical practice guidelines you have to be inclusive and consider all the different types of presentation you may see,” he responded. “The panel agreed that corticosteroid injections have to be used judiciously, and by no means do we use them now as we did ten years ago, when patients would get a series of three weekly injections. By the same token, we don’t have evidence-based medicine that says, ‘What is the proper time for that?’ An injection in the first appointment would be for the patient who has had problems for a long time and is acutely symptomatic.”

Reprinted with permission from Thomas JL, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain: a clinical practice guideline-revision 2010. J Foot Ankle Surg 2010;49(3 Suppl):S2.

Although Thomas emphasized the importance of examining the guidelines’ text rather than going just by the flowcharts, in fact the text provides no further clarification of the authors’ intent in this matter. It simply reads, “Initial treatment options may include…a corticosteroid injection localized to the area of maximum tenderness.” The guidelines from nine years ago read, “Initial treatment options may include…corticosteroid injections for appropriate patients.”4 It’s difficult to discern the change in approach.

Some research supports concern. For example, a 2005 paper in the Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine found that “existing medical literature does not provide precise estimates for complication rates….Tendon and fascial ruptures are often reported complications of injected corticosteroids.”5

Necessary Surgery?

Clough also expressed concern that the guidelines did not clarify which aspects of orthotic intervention were most likely to affect fasciitis.

“Fasciitis is primarily a mechanical malfunction of the foot, and the orthotic, along with stretching and gait training, is very important in establishing normal function,” he said. “But the ACFAS guidelines don’t expound on what an orthotic approach should be. Almost 100% of my plantar fasciitis patients are not walking correctly, and a lot of that has to do with dysfunction of the first ray. Correcting that with an orthotic modification, then doing the appropriate gait training to get them to use their first ray and engage the windlass mechanism, is a very effective way to treat fasciitis.”

“Fasciitis is primarily a mechanical malfunction of the foot, and the orthotic, along with stretching and gait training, is very important in establishing normal function,” he said. “But the ACFAS guidelines don’t expound on what an orthotic approach should be. Almost 100% of my plantar fasciitis patients are not walking correctly, and a lot of that has to do with dysfunction of the first ray. Correcting that with an orthotic modification, then doing the appropriate gait training to get them to use their first ray and engage the windlass mechanism, is a very effective way to treat fasciitis.”

Clough has not had to resort to plantar fascia surgery for fasciitis in his past 15 years of practice, and he is troubled at how often some of his colleagues do.

“I worry that we are going too fast from Tier 1 to Tier 2, then to Tier 3,” he said. “Not all doctors adhere to these tiers. They don’t understand the proper use of orthotics, stretching, and gait training; they view them as just another stepping stone to surgery. This is a mechanically induced problem, and if patients are not responding to mechanical control of the foot, we need to reevaluate and make changes. Watching your patients walk can be very instructive. Perhaps surgery is appropriate for hallux limitus or an extremely unstable flatfoot deformity, but I fail to see the indication for a plantar fasciotomy, no matter how many ways you can think of to do it.”

Thomas agreed that roughly 95% of patients get better without surgery.

“In the algorithms we recommend exhaustive nonoperative care for a minimum of six months,” he said. “Surgery is really the end stage, only if you’ve failed nonoperative approaches. But it is very worthwhile for folks who have gotten to that point and has a high success rate, approaching 90%.”

However, Clough noted a scarcity of studies assessing long-term outcomes following plantar fasciotomy.

“Is there an increase in bunion deformities, in hammer toes, in shin splints? Is there a flattening of the foot?,” he asked. “You look at them after a year and you say, ‘they got better.’ But five years down the line are they still better, or are they coming in with other problems?”

Some research supports Clough’s concerns, including at least one long-term study. In 2009, researchers reviewed 22 years’ worth of studies, then reported in the Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association that research in cadaver feet suggested that plantar fasciotomy led to loss of integrity of the medial longitudinal arch. They also reviewed in vivo studies, which found satisfactory clinical outcomes but a decrease in medial longitudial arch height and a medial deviation of the center of pressure of the weightbearing foot.6 One long-term study of fasciotomy (4.5- to 15-year follow-up) reported that it was successful (i.e., with good or excellent results) 71% of the time, but that problems included slower recovery and abnormalities of foot function.7

The PT’s Perspective

The authors of the APTA guidelines, not surprisingly, found significant evidence to support the use of physical therapy in treating heel pain and fasciitis (though it should be noted that an MD was among the authors).

Recommendations for the physical exam include palpation, talocural joint dorsiflexion range of motion, the tarsal tunnel syndrome test, the windlass test, and longitudinal arch angle. Interventions include activity limitation, dexamethasone delivered via iontophoresis, manual therapy, stretching of the calf and plantar fascia, night splints, and prefabricated or custom foot orthoses.

“We wanted to review the best current evidence for how one should go about the exam, and also look at interventions that fall within the realm of physical therapy,” said Thomas McPoil, PT, PhD, lead author of the guidelines. McPoil, who is the regents professor of physical therapy and co-director of the Laboratory for Foot and Ankle Research at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, added that the authors had hoped to include exercise but ultimately opted not to.

“Most physical therapists feel that exercise is important, for both the muscles of the lower leg and the intrinsic muscles of the foot, but we didn’t have the evidence to substantiate including that,” he said.

A recent randomized clinical trial further bolstered the efficacy of manual therapy, however;2 and Michael Gross explained why stretching the calf actually works.

“When you get a lot of tension in the Achilles, it grabs onto the calcaneus and pulls it slightly posterior, which stretches the plantar fascia,” he said. “And if you have tightness in the calf muscles, it will restrict the motion of the ankle joint and drive it to the other joints of the foot. That, in turn, can cause the arch to collapse and put even more stress on the plantar fascia.”

“What is preventing our patients from doing what they want to do is edema, inflammation of periarticular tissues, muscle weakness, and pain,” McPoil added. “In physical therapy, we have to look more at impairment, functional limitation, and disability rather than trying to come up with a specific diagnosis.”

McPoil’s colleague and coauthor, Mark Cornwall, PT, PhD, CPed, agreed. “Plantar fasciitis is a medical diagnosis, not a physical therapy diagnosis,” Cornwall said. “The physical therapist would say, ‘I know you have fasciitis, but what can you do? What can’t you do? Why can’t you do it?’”

According to McPoil, the feedback from therapists has been positive.

“It’s having an impact,” he said. “Physical therapists like the guidelines because it provides a consensus of the available literature. They can say, here is what we’re doing, and here’s the evidence to support that.”

New studies make it important to update the guidelines every four or five years if possible, McPoil said; the 2008 guidelines are the first set issued by the APTA. He is also more struck by the similarities between the various guidelines than by their differences.

“If you allow for the differences in scope of practice, the new guidelines from ACFAS are very similar to what we published,” he said. “I was glad to see that, because I thought, good—we are pretty much right on.”

Cary Groner is a freelance writer based in the San Francisco Bay area.

References

1. Thomas JL, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain: a clinical practice guideline-revision 2010. J Foot Ankle Surg 2010;49(3 Suppl):S1-19.

2. Cleland JA, Abbott JH, Kidd MO, et al. Manual physical therapy and exercise versus electrophysical agents and exercise in the management of plantar heel pain: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2009;39(8):573–585.

3. McPoil TG, Martin RL, Cornwall MW, et al. Heel pain—plantar fasciitis: clinical practice guidelines. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008;4(38):A1–18.

4. Thomas JL, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR, et al.The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain. J Foot & Ankle Surg 2001;40(5):329–340.

5. Nichols A. Complications associated with the use of corticosteroids in the treatment of athletic injuries. Clin J Sport Med 2005;15(5):370–375.

6. Tweed JL, Barnes MR, Allen MJ, Campbell JA. Biomechanical consequences of total plantar fasciotomy: a review of the literature. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2009;99(5):422–430.

7. Daly P, Kitaoka H, Chao E. Plantar fasciotomy for intractable plantar fasciitis: clinical results and biomechanical evaluation. Foot Ankle 1992;13(4):188–195.

I read this article and finally felt like there was an article written with some really logical persperspective on treatment of plantar fascitis. I do a lecture series on foot and ankle biomechanics and I spend a lot of time on this subject. I have long practiced and taught tthat fascitis is almost purely a mechanical issue.. I teach my students that fascitis, post tibtibial tendonitis, etc. are not diagnoses but merely a symptom of a biomechanical diagnoosis. I feel the 2 biggest factors are subtalar mobility and 1st ray dysfunction. I feel improper assessment of subtalar mobility is why orthotic intervention often fails. More often than not PF patients have a lack of rearfoot mobilty, with a subsequent increase in mid and fore foot mobility. Orthotics need to be customized based upon that. First ray mobility goes without saying as far as its effect on the windlass mechanism. I appreciate your article here and I apreciate the crossover perspectives b/w PT and podiatry. Thanks agaain

Plantar Fascitis has no relationship to the presen or absence of heel spurs. I agree that it is caused by a repetitive micro sprain of the plantar fascia. tx clog type shoe ,ice ,no ambulation bare foot or in low heel shoes. Best results with higher heel shoe ie clogs. 95% of symptoms do not require surgery,injections or ‘orthotics ‘

Physical therapist, Michael Gross, PT, PhD, is failing to take into consideration the whole person. Plantar fasciosis can be quite painful and causes a significant gait cycle change (antalgic and sidedness shift) that stresses and causes additional debilitating pain in the ankles, knees and hips. Not only is an cortisone injection appropriate, patients many times come in begging for relief of the pain. Further, as podiatrists, we are able to make a full and definitive diagnosis of the root cause of planter heel pain, applying the appropriate treatments, and speeding recovery. We can and do provide the necessary physical therapy necessary to speed healing, and above all else, understand the biomechanical causes of heel pain enabling us to create podiatric, biomechanically corrective, foot orthoses.