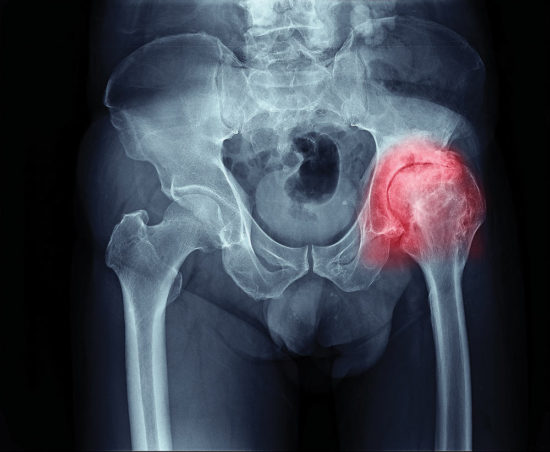

Shutterstock.com 214076914

Although clinicians and researchers have been gathering data for the use of gait therapy in patients with knee OA for some time, its use in hip OA is less far along, but shows promise.

By Nicole Wetsman

Does correcting for gait abnormalities have a role in the treatment of hip osteoarthritis (OA)? Both its use in knee OA and the research that has led to its inclusion in clinical practice guidelines for that condition suggest to some clinicians that principles of gait therapy as applied to knee OA may also apply to hip OA.

Gait changes in hip OA

Clinicians know well the connection between hip OA and abnormal gait—patients walk slowly with a forward lean, and drop the pelvis on the affected side.1,2 The reduced range of motion (ROM) in the hip and knee alter movement and mechanics throughout the lower extremity.3 Pain can further reduce ROM.4

The relationship between gait biomechanics and OA can be viewed as a chicken-and-egg problem, observed Robin Queen, PhD, associate professor of biomedical engineering and mechanics at Virginia Tech: the directionality remains unclear. “We don’t know whether arthritic changes are driving gait changes, or gait is causing the arthritis,” Queen says.

These biomechanical changes can, however, be observed once cartilage begins to deteriorate, said Deborah Solomonow-Avnon, PhD, a researcher on the faculty of mechanical engineering at the Technion—Israel Institute of Technology, in Haifa, Israel, and lead author of a recent paper on biomechanical therapy for hip OA. A patient will adopt a pathological gait–pain restricts how the patient uses their muscles, causing a cycle of gait change leading to pain, and further gait change. Proof that compensatory strategies lead to disease progression is lacking, but abnormal gait patterns might increase abnormal loading on the joints of patients with hip OA, said Keelan Enseki PT, MS, orthopedic physical therapy residency director at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The logic behind gait therapy, then, is to correct for abnormal stress that changes associated with hip OA may have on joints. “We can correct what we know are faulty mechanics,” Enseki said. “Patients perform better, and perhaps, we can [slow] progression of the OA.”

Gait as treatment target

The pace of research on gait and hip OA has increased along with advances in research in the knee, reflecting a trend in osteoarthritis: “The knee sets the tone, and the hip will follow,” said Enseki. OA of the knee is more prevalent than hip OA; the prevalence of symptomatic OA in patients older than 45 years is approximately 16%, compared with 9% for hip OA.5 Queen observed that patients with hip OA tend to have more degeneration than knee patients before seeking medical help, and Enseki surmised that because patients may more easily adapt to the limitations of hip OA compared with the same degeneration seen in the knee, physical therapists and physicians may see fewer hip OA patients.

Gait modification interventions have been found to reduce loading on the knee in patients with knee OA, and to reduce pain and symptoms. “It at least reduces pain,” Queen said. Investigators have assessed foot orthoses to assist in gait therapy for knee OA patients, with mixed results.6 Clinical practice guidelines for both the Osteoarthritis Research Society International and the European League Against Rheumatism have suggested that orthoses might be useful.7

From knee to hip

iStockphoto.com 522886485

Solomonow-Avnon and her collaborators took a step toward applying those findings from the knee to the hip through research published over the past several years using the APOS biomechanical device to drive biomechanical changes. The device consists of 2 elements attached to the sole of the shoe at the heel and at the ball of the foot. The positioning of the 2 pieces is adjustable, allowing for individual calibration. The device forces the patient to walk in a specific manner. Because the foot is the point of contact between the ground and the body, Solomonow-Avnon said, manipulating that intersection can impact loading on the joints of the lower extremity.

In a 2013 study, the authors reported on gait patterns, pain, and quality of life of 60 hip OA patients using the device for 1 hour a day. After the 12-week trial, patient walk speed, step length, and cadence had improved from baseline. Patients also had reduced pain and stiffness, as measured on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC).8

Solomonow-Avnon then looked more closely at specific gait changes caused by the same device in a pilot study of 12 healthy men, and demonstrated that walking with the device led to increased hip abduction and decreased forces on the hip joint.9

The group next conducted a longitudinal study of a gait treatment program using the device in patients with hip OA. Twenty-one women with hip OA completed the year-long program, with testing at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months, with patients gradually increasing their use of the device from 10 minutes to 2 hours a day.10 Over the 12 months of the study, patients reported improved quality of life and physical function, including measures included on the WOMAC. Importantly, gait speed increased.

Study limitations were the inclusion of only women, and lack of control group, and further trials are needed to confirm the initial promising findings, Solomonow-Avnon said.

“For the first time, we showed you can impact the hip using manipulations at the foot, and that we can see improvement in hip OA using this concept,” she said.

Implementing in practice

Current first-line treatments for hip OA that are supported by research findings include 1) patient education and, 2) strength, flexibility, and endurance training, Enseki said. Solomonow-Avnon’s research is an initial step toward evidence for the use of gait therapy in hip OA, which presently falls under the category of treatments that may be employed by clinicians with the understanding that more studies are needed.

Although the evidence for gait therapy and hip OA remains limited, Enseki said that it is sometimes used by therapists and doctors working directly with patients, and anecdotal evidence from that use supports it as a strategy. “We often utilize those sorts of interventions, even though the evidence isn’t as strong yet,” he says. In individual cases in which gait retraining has been included in therapy, Enseki says he’s seen good results.

From a clinical perspective, Queen said, a major goal of OA treatment is to ease pain, and gait retraining might be among the methods used to reach that goal, by, for example, ensuring the patient is not hiking up their hips, or walking with a Trendelenburg gait pattern.

Where do we go from here?

Shutterstock.com 461189074

Hip OA treatment focuses on functional outcomes, Enseki said. An overarching goal is to maintain the patient’s lifestyle, which might include delaying surgery as long as possible. Gait therapy might contribute to reaching that goal. Queen is uncertain whether orthoses or similar devices are the best approach to gait therapy for all patients. “No 2 patients are going to alter their gait mechanics in the same way,” she said. “It may help a subset of people, but it’s going to be a challenge to really make it a broad solution.”

Gait therapy research also fits neatly into what Enseki describes as a broader trend: a focus on hip preservation across the lifespan, with early modifications. “We’re trying not to reach the point of hip OA,” he said, noting that gait and higher-level biomechanics might have a role.

Overall, the literature with regard to gait therapy for hip OA is in early stages, particularly compared with other areas of orthopedic medicine. Despite early, seemingly positive results for hip OA and gait intervention, continued inquiry and expanded lines of research are the most important next step, Enseki said.

Nicole Wetsman is a freelance writer.

- Eitzen I, Fernandes L, Nordsletten L, Risberg MA. Sagittal plane gait characteristics in hip osteoarthritis patients with mild to moderate symptoms compared to healthy controls: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:258.

- Zeni J Jr, Pozzi F, Abujaber S, Miller L. Relationship between physical impairments and movement patterns during gait in patients with end-stage hip osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(3):382-389.

- Schmitt D, Vap A, Queen RM. Effect of end-stage hip, knee, and ankle osteoarthritis on walking mechanics. Gait Posture. 2015;42(3):373-379.

- Hurwitz DE1, Hulet CH, Andriacchi TP, et al. Gait compensations in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and their relationship to pain and passive hip motion. J Orthop Res. 1997;15(4):629-635.

- Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26-35.

- Rodrigues PT, Ferreira AF, Pereira RM et al. Effectiveness of medial-wedge insole treatment for valgus knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(5):603-8.

- Hinman RS, Hunt MA, Simic M et al. Exercise, gait retraining, footwear and insoles for knee osteoarthritis. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep. 2013;1(1):21-28.

- Drexler M, Segal G, Lahad A et al. A non-invasive foot-worn biomechanical device and treatment for patients with hip osteoarthritis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2013;8:13.

- Solomonow-Avnon D, Wolf A, Herman A et al. Reduction of frontal-plane hip joint reaction force via medio-lateral foot center of pressure manipulation: a pilot study. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(2):261-269.

- Solomonow-Avnon D, Herman A, Levin D et al. Positive outcomes following gait therapy intervention for hip osteoarthritis: A longitudinal study. J Orthop Res. 2017;35(10):2222-2232.