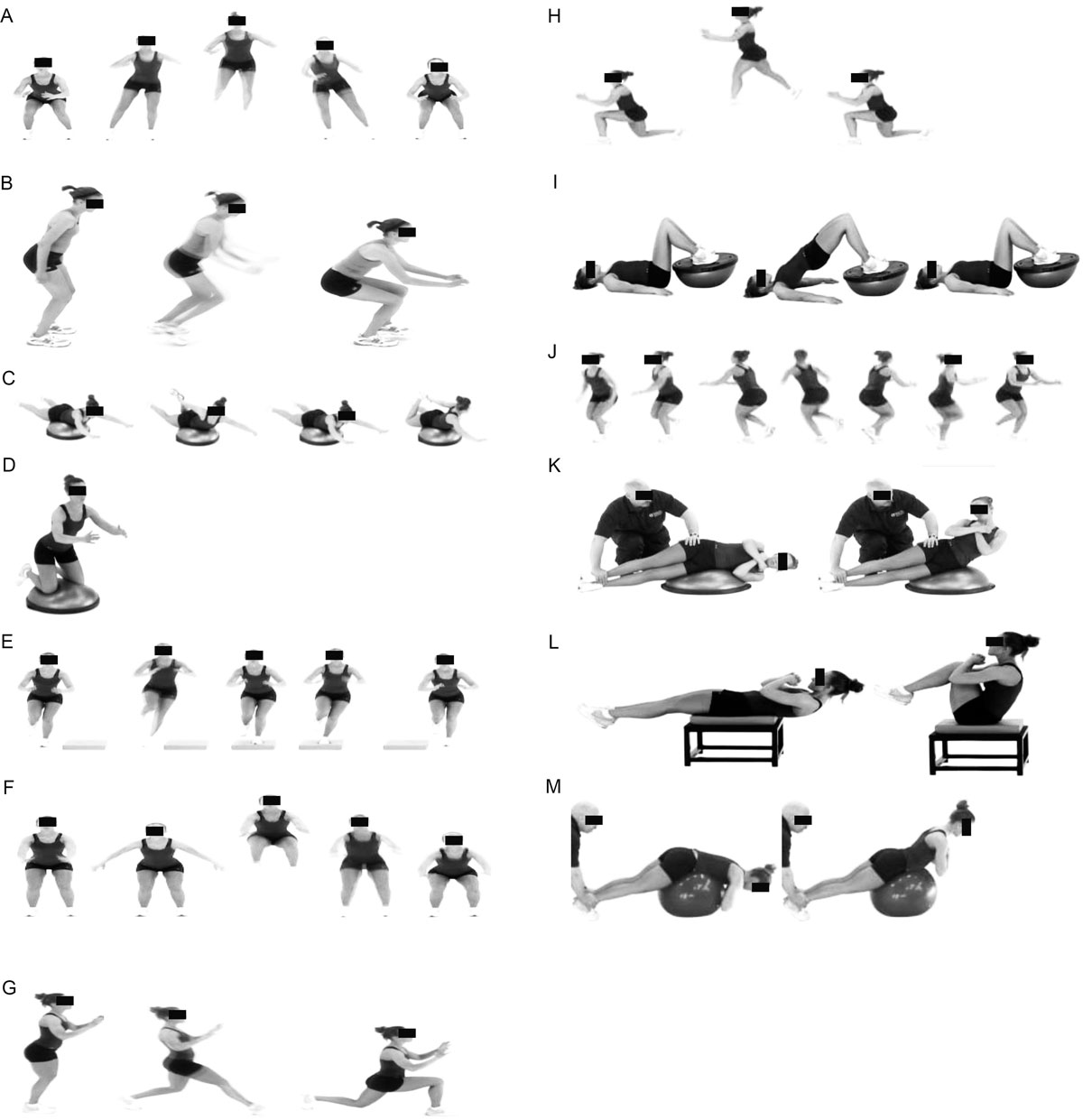

Figure. School-based NMT program has proved effective.9

Shown are examples of NMT intervention exercises that were completed preseason: A Lateral jump and hold. B Step hold. C BOSU (round) swimmers. D BOSU (round) double-knee hold. E Single-legged lateral AIREX hop-hold. F Single tuck jump with soft landing. G Front lunges. H Lunge jumps. I BOSU (flat) double-legged pelvic bridges. J Single-legged 90° hop hold. K BOSU (round) lateral crunch. L Box double crunch. M Swiss ball back hyperextensions.

Reproduced with permission of National Athletic Trainers’ Association. All rights reserved.

5.5 million children and adolescents are injured playing sports annually. Most of these injuries are preventable, the CDC says.

By Warren J. Potash

More than 30 million children and adolescents participate in organized sports in the United States; according to the Centers for the Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), that number is on the rise.1 Regrettably, the rate of youth sport injuries is also increasing: An estimated 3.5 million children younger than 14 years and 2 million high-school teenagers receive medical treatment for a sports injury annually.2

In 2011, Edward Wojtys, MD, director of sports medicine at the University of Michigan, said that the rate of youth sports injury is becoming a public health crisis.3 As a leading orthopedic surgeon and researcher, he led the cry for decreasing what has become an unacceptable rate of injury. In 2012, I called for a sea change in regard to how parents, trainers, and coaches view and train child athletes.4

Nevertheless, in 2019, the injuries continue, and that sea change has not yet happened.

This Crisis Is Preventable

According to the CDC, more than half of sports injuries in children are preventable.5 Research suggests that sports specialization at too young an age plays a big role in the incidence of youth sports injury. A 2016 report from the American Academy of Pediatrics explained that the “increased emphasis on sports specialization has led to an increase in overuse injuries, overtraining, and burnout.”6 Timothy McGuine, PhD, distinguished scientist at the University of Wisconsin Sports Medicine Center, and colleagues found that “kids who have higher levels of [sport] specialization were at about a 50% greater risk of having an injury.”7

The injury rate among adolescent female athletes is particularly concerning. Since passage of Title IX legislation more than 40 years ago, female participation in youth sports has increased dramatically.8 Studies have shown that adolescent female athletes are 3 to 8 times more likely to suffer an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury than adolescent male athletes participating in the same sport.9

My colleagues and I looked at mechanisms of injury in adolescent female athletes and developed the Balance, Neuromuscular Control, Proprioception–Central Nervous System (BNP–CNS) training program,10 also known as neuromuscular training (NMT). Since 1995, the guidelines that are part of this program have helped prevent injuries in more than 600 teenage female athletes under my care.

The “Black Swan” Effect

Table 1. WHY DO SO MANY YOUNG FEMALE ATHLETES SUFFER KNEE INJURY?12-14

- Most injuries occur in the last one-third of practice and games, when fatigue and overuse are most likely to occur

- Adolescent female athletes have a myriad of challenges at puberty that male athletes of the same age do not

- Most volunteer youth sports coaches focus primarily on skills training*

- Safe and age-appropriate training to play sports is not emphasized

- The critical importance of central nervous system challenges for the safety of all youth athletes is not recognized in general—especially for female athletes

- Long-term player development of younger athletes is not valued, compared to winning

- Volunteer coaches do not have to be certified before coaching the athletes in their program

*Knee injuries among female youth athletes would decline if more volunteer youth sports coaches incorporated stabilization training into practices.

Timothy Hewett, PhD, professor of orthopedics, physiology, and physical medicine and rehabilitation at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, has described the increased rate of female ACL injuries as a so-called black swan event.11 The name refers to a theory, formulated by Taleb, of the impact of a highly improbable event12—best described as an event that cannot be expected and can only be realized after empirical analysis reflects unexpected results.

“I was only a page or two into the prologue [of Taleb’s book, The Black Swan],” Hewett wrote, “when I realized that a noncontact ACL injury is, by Taleb’s definition, a ‘black swan’.”11

No one thought that ACL injuries—many of which lead to season-ending surgery and rehabilitation—would become such a challenge for adolescent female athletes. There are a number of reasons why so many young female athletes suffer a knee injury (see Table 1)10,13,14; if strength was the only factor, the challenge of helping adolescent female athletes would be much easier. Reducing the injury rate among adolescent and teen female athletes must take a different approach than in age-matched male athletes, with a longer view in mind.

A recent review by Simon and colleagues showed that, not only do females have an increased risk of ACL injury, they are also at increased risk of osteoarthritis within as few as 12 years after ACL injury.15 Furthermore, Simon points to data that show that female patients who undergo ACL reconstruction are more likely (hazard ratio, 1.58) than males to require knee arthroplasty after only 15 years.

All Female Athletes Are Challenged at Puberty

A number of physiologic and physical changes that affect all females at puberty influence female adolescents having a much higher injury rates than age-matched male athletes (see Table 2).10 Neuromuscular training plays an important role in helping female athletes deal with these challenges. If more adolescent athletes cross-trained or played more than 1 sport, sports injuries could decrease. Indeed, the American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine said that “there is no evidence that young children will benefit from early sport specialization in the majority of sports,” compared to the risks of overuse injury and burnout.16

Balance: The Core of NMT

Balance is key for developing athleticism, and single-leg balance for lower-body stabilization is the first step in ensuring an athlete is balanced back to front and side to side. Neuromuscular training is acknowledged as the most effective way to minimize risk of injury and develop athleticism among athletes,9 and single-leg stabilization is the key to helping all teenaged female athletes reduce their risk of ACL injury.

In 1997, Lephart and colleague showed that training the knee in a slightly flexed position optimally recruits microneurotransmitters under the patella17,18; such recruitment makes a significant difference for optimal protection of the knee joint and is a key factor for minimizing risk of ACL injury. Beginning in 2000 in my practice, changing the training approach to a flexed knee position reduced the number of training sessions it took to stabilize the knee: from 9 to 12 down to 6 to 9. The center of the knee must track between the first and second toes; I use a posterior-to-distal approach with baseline and ongoing assessments, seeking a maximum 3% to 5% difference from side to side and front to back.

The objective of NMT is to stabilize the knee and improve the ability to generate a fast and optimal muscle firing pattern by increasing joint stability during sports participation. Neuromuscular training is rooted in physical therapy rehabilitation protocols that follow injury or surgery. de Andrade Gomes and Pinfildi have described a 6-station circuit for NMT of the knee that is part of an integrated, safe, and age-appropriate training program.19

Foss and colleagues found that middle- and high-school students who participated in a school-based NMT program of trunk and lower-extremity exercises (see Figure) had a lower incidence of sports-related injuries, compared to those who participated in a program consisting of resisted running using elastic bands.9

Every Athlete, All Year Long

Table 2. PUBERTAL CHANGES THAT PUT ADOLESCENT FEMALE ATHLETES AT HIGHER RISK OF INJURY12

- Diminished neuromuscular spurt at puberty (compared to males)

- Female athlete triad (osteoporosis, eating disorders, and amenorrhea)

- Wide hip-to-knee ratio (Q angle)

- Jumping using quadriceps and landing hard

- Running upright

- Hormonal changes (possible)

- Muscular imbalance and weaknesses

- Lax joints

- Playing sports without training

- Growth plate and joint development

- Lack of coordination

- Properties of ligaments and tendons

- Neuromuscular fatigue

- Tendon response to exercise

- Central nervous system fatigue

Despite overwhelming evidence—more than 300 articles were found in a recent PubMed search—supporting the importance of NMT for every athlete, adolescent and high-school athletes are not required to participate in NMT before, during, or after their competition season. Safe and age-appropriate training should take place before the season begins and be maintained throughout the season.

There is no downside to safe and age-appropriate training. The great majority of young athletes will display more athleticism, and a trained athlete who is injured will return to play more quickly than an untrained athlete.

Lower-body-stabilization training (integrated with full-body or core training) is as effective for older female and male athletes as it is for adolescent female athletes. Training to challenge every athlete throughout the year, coupled with having a peak performance cycle as many as 5 or 6 times (i.e., periodization or sport performance planning), ensures successful transition onto the field of play.

Trainers should develop safe, evidence-based exercises, such as those included in the BNP-CNS training program, that do not compromise the female athlete’s body while she works to improve her athleticism. Adopting a less-is-more philosophy allows every female athlete to minimize risk of injury while performing at an optimal level. An ACL injury should not be an unavoidable consequence of participating in sports for female athletes.

Warren Potash (warren.potash34@gmail.com) is a sports performance coach who has been helping adolescent female athletes since 1995, primarily to minimize their risk of ACL injury as part of an integrated training program.

Mr. Potash owns the web domain www.learn2trainsafely.com.

—Female college athlete and Learn2TrainSafely program graduate

- Sheu Y, Chen LH, Hedegaard H. Sports- and recreation-related injury episodes in the United States, 2011–2014. National health statistics reports, number 99. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr099.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine. STOP Sports Injuries : Youth sports injuries statistics. www.stopsportsinjuries.org/STOP/Resources/Statistics/STOP/Resources/Statistics.aspx . 2017. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Longman J. For women in sports, A.C.L. injuries take toll. New York Times. March 26,2011. www.nytimes.com/2011/03/27/sports/ncaabasketball/27acl.html. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Potash WJ. They’re Not Boys: Safely Training the Adolescent Female Athlete. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sports and recreation-related injuries. www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/toolstemplates/entertainmented/tips/SportsInjuries.html. September 15, 2017. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Brenner JS; Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Sports specialization and intensive training in young athletes. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3). pii:e20162148.

- McGuine TA, Post EG, Hetzel SJ, et al. A prospective study on the effect of sport specialization on lower extremity injury rates in high school athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(12):2706-2712.

- Horowitz S. ACL injuries: Female athletes at increased risk. MomsTeam. www.momsteam.com/health-safety/muscles-joints-bones/knee/acl-injuries-in-female-athletes. August 7, 2014. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Foss KDB, Thomas S, Khoury JC, et al. A school-based neuromuscular training program and sports-related injury incidence: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. J Athl Train. 2018;53(1):20-28.

- Potash WJ. Researchers have identified key differences between teen females and males. www.learn2trainsafely.com/60.html. Accessed April 15, 2019.

- Hewett HE. Prevention of non-contact ACL injuries in women: use of the core of evidence to clip the wings of a “black swan.” Curr Sports Med Rep. 2009;8(5):219-221.

- Taleb NN. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. New York, NY: Random House; 2008.

- LaBella CR, Huxford MR, Grissom J, et al. Effect of neuromuscular warm-up on injuries in female soccer and basketball athletes in urban public high schools: cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(11):1033-1040.

- Zaichkowsky L, Peterson D. The Playmaker’s Advantage: How to Raise Your Mental Game to the Next Level. New York, NY: Gallery/Jeter Publishing; 2018.

- Simon D, Mascarenhas R, Saltzman BM, et al. The relationship between anterior cruciate ligament injury and osteoarthritis of the knee. Adv Orthop. 2015;2015:928301.

- LaPrade RF, Agel J, Baker J, et al. AOSSM Early Sport Specialization Consensus Statement. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(4):2325967116644241.

- Borsa PA, Lephart SM, Irrgang JJ, et al.. The effects of joint position and direction of joint motion on proprioception sensibility in anterior cruciate ligament-deficient athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(3):336-340.

- Lephart SM, Fu FH. Proprioception and Neuromuscular Control in Joint Stability. Champaign IL: Human Kinetics; 2000.

- de Andrade Gomes MZ, Pinfildi CE. Prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries and a proposal for neuromuscular training to prevent lower limb injuries in Brazilian Army soldiers: an observational study. Mil Med Res. 2018;5(1):23.