By Lisa H. Jain, DPT, OCS; Kevin J. McCarthy, MD; Michael Williams, PT, OCS; Marie Barron, PT, OCS; Nick Bird, MPT; Brian Blackwell, PT, OCS; G. Andrew Murphy, MD; David R. Richards, MD; Susan Ishikawa, MD; and Margaret Kedia, PhD, DPT

By Lisa H. Jain, DPT, OCS; Kevin J. McCarthy, MD; Michael Williams, PT, OCS; Marie Barron, PT, OCS; Nick Bird, MPT; Brian Blackwell, PT, OCS; G. Andrew Murphy, MD; David R. Richards, MD; Susan Ishikawa, MD; and Margaret Kedia, PhD, DPT

Research supports eccentric strengthening for treatment of midportion Achilles tendinopathy, but a new study suggests the same approach may not be warranted for insertional tendinopathy. Other physical therapy techniques, however, work well in both patient populations.

Achilles tendinosis is a chronic condition characterized by diffuse thickening of the tendon, without histologic evidence of inflammation, which is caused by increased demand on the tendon.1 When such tendinopathy occurs 2 to 6 cm proximal to the calcaneal insertion, it is classified as midportion Achilles tendinosis.2 When the tendinopathy occurs at the insertion of the Achilles tendon onto the calcaneus, it is classified as insertional Achilles tendinosis.3

Achilles tendinopathy is common among adult athletes, particularly runners and middle-aged people,4-6 but also is seen among patients with a sedentary lifestyle.7 The etiology of insertional Achilles tendinopathy may be attributed to training errors, nonoptimal footwear, uneven training surfaces, muscle weakness, and biomechanical factors, such as cavus foot, pes planus, genu varum, decreased ankle dorsiflexion, decreased mobility of the subtalar joint, and leg-length differences.8

The American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society recommends at least six months of nonsurgical treatment before clinicians consider surgical intervention for Achilles tendinopathy. Conservative treatment includes stretching exercises for the Achilles tendon, night splints, custom orthoses, rest, corticosteroid injections, heel lifts, cryotherapy, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.9

In addition, eccentric training has become a popular and successful treatment option for tendinosis. An eccentric contraction occurs when a muscle lengthens as it yields to an external resistance. Eccentric contractions have a much lower metabolic cost than concentric contractions, meaning fewer muscle fibers are recruited to produce the same force as a concentric contraction. Previous research has revealed that eccentric training provides greater increases in strength and greater muscle hypertrophy compared with concentric training.10,11

Recent evidence adds further support for the use of eccentric strengthening specifically for Achilles tendinopathy. Langberg et al12 showed eccentric training causes an increase in type I collagen in diseased Achilles tendons, which suggests that eccentric training stimulates mechanoreceptors in tenocytes to produce collagen, thus helping to reverse the tendinopathy cycle. Eccentric training lengthens the musculotendinous junction, thus applying less strain on the Achilles tendon during movement.13 Finally, eccentric training reverses the process of neovascularization and nerve ingrowth, which is a cause of pain with Achilles tendinosis.14

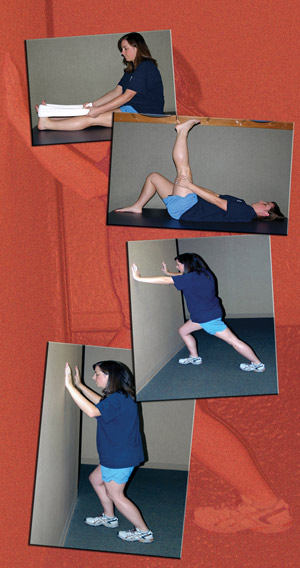

Figure 1. Conventional stretches for insertional Achilles tendinopathy. (A) Gastrocnemius stretch. With the knee straight and heel on the floor (involved foot back), the patient leans forward. (B) Soleus stretch. With the knee bent and the heel on the floor (involved foot back) the patient leans forward. (C) Hamstring stretch. Lying supine, the hands (or a towel) are placed around the posterior aspect of the knee. The knee is slowly straightened until a stretch is felt. Then, keeping this position, the foot is pulled toward the face. (D) Sitting in an upright position with the involved knee straight, a towel is placed around the ball of the foot. Using both hands, the patient pulls the towel, bending the foot toward the face. (Reprinted with permission from Kedia et al).24

Stanish et al stressed the importance of eccentric training as part of the clinical rehabilitation of tendon injuries.15 Influenced by this work, Alfredson et al designed a special heavy-load eccentric strengthening protocol for midportion Achilles tendinosis.16 The results showed that, following a 12-week training period, 100% of the participants were able to return to their preinjury levels with full running activity.16 In a study by Fahlström et al, 89% of patients with midportion Achilles tendinosis returned to their preinjury activity levels after a 12-week eccentric training regimen, with a significant reduction in pain.17 Mafi et al, Roos et al, and Ohberg et al also reported comparable results.18-20

Results from four other studies that evaluated the effects of eccentric training for insertional Achilles tendinosis17,21-23 have not been as promising as the aforementioned studies of patients with midportion Achilles tendinosis. Fahlström et al, Jonnson et al, Knobloch, and Rompe et al, in independent studies of 12-week eccentric training protocols utilizing a numerical pain scale as an outcome measure, reported an overall decline of 2.7 points on a 10-point scale (weighted mean).17,21,23 Three of the studies17,21,23 documented patient satisfaction, reporting a combined result of “extremely satisfied” or “satisfied” in only 42% of the participants.3

Our previously published study24 investigated the effect of eccentric training and conventional treatments on pain and function in patients with insertional Achilles tendinosis.

Kedia et al24 study design

We collected data from 2007 to 2010. The sample population consisted of patients aged 18 years and older who had received a diagnosis of insertional Achilles tendinosis and experienced symptoms for at least three months. The diagnosis of insertional Achilles tendinosis was made when the primary area of pain was localized to the Achilles tendon at its insertion, and there was pain with activity or start-up pain.

Patients were randomly assigned to either a control group, which received conventional physical therapy treatment, or an experimental group that received conventional physical therapy treatment (same as the control group) plus eccentric strengthening. Conventional physical therapy included stretches for the gastrocnemius, soleus, and hamstring muscles (Figure 1); ice massage on the Achilles tendon twice a day for five to 10 minutes; a dorsal night splint that held the ankle in a neutral position; and bilateral adjustable heel lifts, which started at 3/8″ and were lowered 1/8″ every two weeks, to no lift at all at six weeks. The patients in conventional therapy did not perform any strengthening exercises.

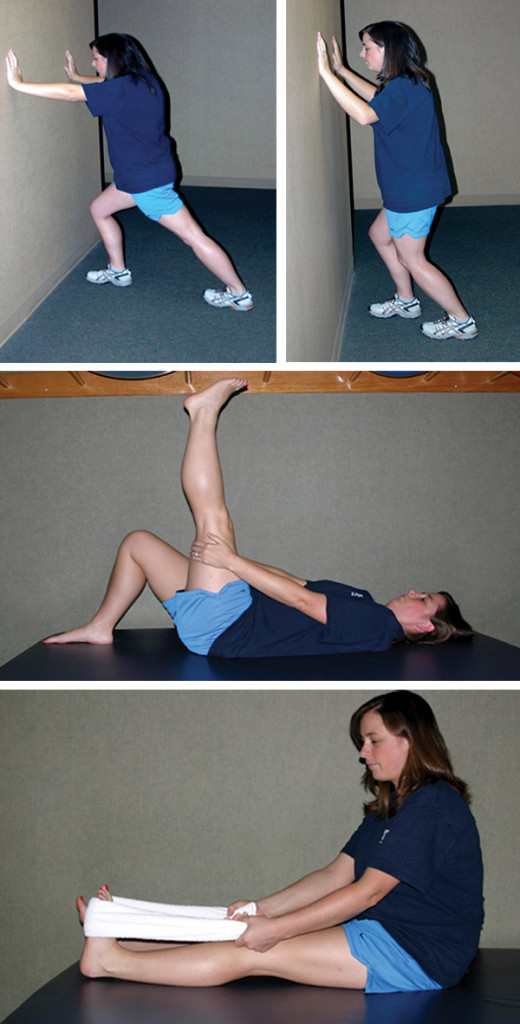

The patients in the experimental group were instructed to perform all of the above plus two eccentric strengthening exercises: (1) Having the patient stand on one step and use both feet to rise onto the balls of the feet, slightly flex the knee of the involved leg, lift the uninvolved leg, and then lower the involved heel from plantar flexion to dorsiflexion in a count of five (two sets of 15 repetitions), and (2) having the patient repeat the aforementioned exercise, only this time with the involved knee straight, again slowly lowering from plantar flexion to dorsiflexion to a count of five (two sets of 15 repetitions) (Figure 2). The eccentric strengthening protocol used one less set of 15 repetitions than Fahlström et al17 to accommodate the varied activity level of our patient population.

Patients were instructed in all the exercises and issued the heel lifts at the initial evaluation. They returned to the physical therapy department to monitor progress and check patient performance and exercise technique at one, three, and five weeks after the evaluation. However, patients were instructed to continue performing the protocol for a total of 12 weeks, even though they were not still seeing the physical therapist.

Figure 2. Eccentric training exercises. In the first exercise, the patient stands bearing weight on the involved foot in plantar flexion with the knee slightly bent (left) and slowly lowers the heel into dorsiflexion to a count of five (center). In the second exercise, the patient stands bearing weight on the involved foot in plantar flexion with the knee straight and lowers the heel to a count of five (right). (Reprinted with permission from Kedia et al.24)

Orthopedic surgeons who specialized in treating the foot and ankle made the initial diagnosis and collected data at baseline, six weeks, and 12 weeks. The surgeons were blinded to the protocol patients followed. Patient status was measured using a 100-mm visual analog pain rating scale (VAS), with 0 indicating no pain and 100 indicating pain so bad the patient would be in the emergency department; the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and SF-36 Bodily Pain subscale, which are designed to measure patients’ general health status; and the Foot and Ankle Outcomes Questionnaire (FAOQ), which uses 25 questions to determine foot and ankle pain, stability, and the degree of disruption from normal daily activities due to the ankle and foot pain. The physicians also collected demographic and anatomical data, including age, sex, ethnicity, height, weight, tendon calcification present on radiographs, reported activity level, and the patient’s overall complaint and symptoms.

Pain and function outcomes

Sixteen patients followed the experimental protocol, and 20 followed the control protocol. Patients were predominantly women, with only five men in each group. The average age was 51.7 years in the experimental group and 55.3 years in the control group. Body mass index (BMI) indicated obesity in both groups, with a mean of 37.6 for the experimental group and 32.7 for the control group. Most patients (87%) had calcification in the tendon, and three patients experienced symptoms bilaterally. (For our study we included only the tendon deemed worse at initial evaluation, but instructed patients to do the exercises bilaterally for their own benefit.) The self-reported levels of activity at baseline were quite varied, ranging from sedentary to manual labor in a warehouse to recreational athletics.

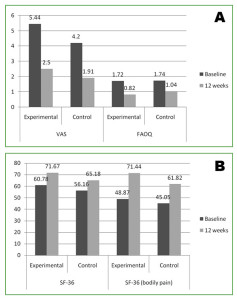

Patients in both groups experienced statistically significant reductions of pain and improvements in function (Wilcoxon U tests) (Figure 3). The addition of eccentric training was not associated with any significant difference in the outcome for any outcome measure (Mann-Whitney tests). Even though the patient population was heavy, patients with higher BMIs did not experience inferior outcomes relative to those with lower BMIs.

Discussion

Our study of patients with insertional Achilles tendinopathy demonstrated no benefit of adding eccentric strengthening to the conventional treatment regimen, which involved stretching, ice massage, night splints, and heel lifts.24 However, both the conventional physical therapy treatment group and the conventional plus eccentric training group demonstrated significant clinical improvement. For both groups combined, 86.7% improved their VAS scores. The mean change in VAS was 20 mm, with a mean percentage difference of 41.3%.24 This is a clinically significant improvement based upon the work of Jensen, Chen, and Brugger, who found that an absolute change between 20 and 30 mm on the 100-mm VAS and a 33% decrease of pain on the VAS were associated with clinically relevant pain relief.25,26 Improvement also was noted in 84.2% of patients on the SF-36, with a mean change of 10;24 an improvement of five points on the SF-36 is considered clinically significant.27,28 In addition, improvement was noted in 73.7% of patients on the Bodily Pain subscale of the SF-36 and in 93.3% of patients on the FAOQ;24 to our knowledge, clinically significant improvement for those measures has not yet been defined.

Importantly, these results indicate that conventional therapy can significantly reduce pain and improve self-reported function in patients with insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Several of the control group interventions that we used, including Achilles stretches and heel lifts, have been used successfully in previous studies of midportion Achilles tendinopathy.9-16 Many patients in our study23 had been treated with at least one of these interventions prior to entry into our study, indicating that combining multiple interventions may be required to achieve clinical success.30

The improvement noted in our study24 was greater than the improvement seen in prior studies of insertional Achilles tendinosis.17,21 Fahlström et al used eccentric strengthening in only 31 patients with insertional Achilles tendinopathy, and only 32% were able to return to their previous activity levels. In a third of their patients, the mean VAS score improved from 68.3 to 13.3; however, the remaining 68% of patients did poorly and experienced little improvement in their VAS score.17 It should be noted that Fahlström et al’s outcome measurement was return to prior level of activity, which usually was a high-level recreational sport, whereas our measure was improvement of an outcome scale, with a population that, while active, was not generally involved in competitive athletics. Jonsson et al21 described a modified eccentric strengthening regimen for insertional Achilles tendinopathy that avoided loading in a position of dorsiflexion. Their results in 27 patients (34 tendons) showed a change in mean VAS from 69.9 to 21 and an overall rate of 67% of patients returning to activity and satisfied with treatment.

Figure 3. Changes in outcome scales. In the top graph, note decrease in the VAS and in the FAOQ, representing improvement in status. In the bottom graph, note increase in the SF-36 Bodily Pain Subscale, representing improvement in status.

As stated previously, eccentric training has been shown to be a successful treatment for midportion Achilles tendinosis.15-20 Although insertional Achilles tendinopathy and midportion tendinopathy are both chronic conditions of the Achilles tendon, and both are associated with increased microcirculatory blood flow, the two are considered distinct clinical entities.31 Insertional tendinopathy is thought by many clinicians to be more difficult to treat. Additionally, patients with posterior heel pain may have other contributing sources of pain, such as retrocalcaneal bursitis, which is diagnosed when the patient has significant pain with palpation anterior to the Achilles tendon. Some patients with insertional Achilles tendinopathy have an associated Haglund’s deformity. The role of the Haglund’s deformity as a pain generator is poorly understood, but it may be an important factor in certain patients. With these multiple differences between midportion and insertional Achilles tendinosis, it is not unexpected that a certain treatment modality, such as eccentric strengthening, may be effective for one condition but not for the other.

Conclusion

In addition to supporting the use of stretching, cryotherapy, night splints, and heel lifts for insertional Achilles tendinopathy, the study by Kedia et al24 specifically isolated the independent variable of eccentric strengthening. Although several previous studies have examined eccentric strengthening for insertional Achilles tendinopathy, to our knowledge, this was the first randomized study comparing identical therapy programs with and without eccentric strengthening. The study findings did not support the use of eccentric strengthening for treatment of insertional Achilles tendinopathy; however, they did support the use of conventional therapy modalities, especially in a less athletic patient population.24

Lisa H. Jain, PT, DPT, OCS, owns Kinetic Physical Therapy and practices at the Healthcare Gallery, both in Baton Rouge, LA. Kevin J. McCarthy, MD, is completing a foot and ankle fellowship in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Tennessee in Memphis and is a staff member at Campbell Clinic Orthopaedics in Germantown, TN. Michael Williams, PT, OCS, is director of physical therapy at Campbell Clinic Orthopaedics in Germantown. Marie Barron, PT, OCS, is the senior manager of physical therapy at Campbell Clinic Orthopaedics in Southaven, MS. Nick Bird, MPT, and Brian Blackwell, PT, OCS, are physical therapists at Campbell Clinic Orthopaedics in Germantown. G. Andrew Murphy, MD, and David R. Richardson, MD, are associate professors in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Tennessee and staff members at Campbell Clinic Orthopaedics in Germantown. Susan Ishikawa, MD, is assistant professor and foot and ankle fellowship director in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Tennessee and a staff member at Campbell Clinic Orthopaedics in Germantown. Margaret Kedia, PhD, DPT, is a physical therapist at Campbell Clinic Orthopaedics in Southaven, MS.

Disclosure: Murphy is an unpaid consultant for Wright Medical Technology and has received research support from Biomimetic Therapeutics and Smith & Nephew. Ishikawa reports institutional support from Smith & Nephew, Stryker, Synthes, OREF (Orthopaedic Research and Education Foundation), and Wright Medical. Murphy, Ishikawa, and Richardson receive royalties from Elsevier. No other authors report any conflicts of interest. No funding or support was received for this paper.

Note: The results of the central study described in this article were originally published by the International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy.24

- Mazzone MF, McCue T. Common conditions of the Achilles tendon. Am Fam Physician 2002;65(9):1805-1810.

- Sorosky B, Press J, Plastaras C, Rittenberg J. The practical management of Achilles tendinopathy. Clin J Sport Med 2004;14(1):40-44.

- Wiegerinck JI, Kerkhoffs GM, van Sterkenburg MN, et al. Treatment for insertional Achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21(6):1345-1355.

- Wilson JJ, Best TM. Common overuse tendon problems: A review and recommendations for treatment. Am Fam Physician 2005;72(5):811-818.

- Jarvinen TA, Kannus P, Maffulli N, Khan KM. Achilles tendon disorders: etiology and epidemiology. Foot Ankle Clin 2005;10(2):255-266.

- Paavola M, Kannus P, Jarvinen TA, et al. Achilles tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84(11):2062-2076.

- Alfredson H, Lorentzon R. Chronic Achilles tendinosis. Recommendations for treatment and prevention. Sports Med 2000;29(2):135-146.

- Morelli V, James E. Achilles tendinopathy and tendon rupture: Conservative versus surgical management. Prim Care 2004;31(4):1039-1054.

- Porter D, Barrill E, Oneacre K, May BD. The effects of duration and frequency of Achilles tendon stretching on dorsiflexion and outcome in painful heel syndrome: a randomized, blinded, control study. Foot Ankle Int 2002;23(7):619-924.

- Gerber JP, Marcus RL, Dibble LE, et al. Effects of early progressive eccentric exercise on muscle structure after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89(3):559-570.

- Gerber JP, Marcus RL, Dibble LE, et al. Effects of early progressive eccentric exercise on muscle size and function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a 1-year follow-up study of a randomized clinical trial. Phys Ther 2009; 89(1):51-59.

- Langberg H, Ellingsgaard H, Madsen T, et al. Eccentric rehabilitation exercise increases peritendinous type I collagen synthesis in humans with Achilles tendinosis. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2007;17(1):61-66.

- Alfredson H. Chronic midportion Achilles tendinopathy: an update on research and treatment. Clin Sports Med 2003;22(4):727-741.

- Ohberg L, Alfredson H. Effects on neovascularization behind the good results with eccentric training in chronic mid-portion Achilles tendionsis? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2004;12(5):465-470.

- Stanish WD, Rubinovich RM, Curwin S. Eccentric exercise in chronic tendonitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1986;(208):65-68.

- Alfredson H, Pietila T, Jonsson P, Lorentzon R. Heavy-load eccentric calf muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. Am J Sports Med 1998;26(3):360-366.

- Fahlström M, Jonsson P, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Chronic Achilles tendon pain treated with eccentric calf-muscle training. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2003;11(5):327-333.

- Mafi N, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Superior short-term results with eccentric calf muscle training compared to concentric training in a randomized prospective multicenter study on patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2001;9(1):42-47.

- Roos EM, Engstrom M, Lagerquist A, Soderberg B. Clinical improvement after 6 weeks of eccentric exercise in patients with mid-portion Achilles tendinopathy– a randomized trial with 1 year follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2004;14(5):286-295.

- Ohberg L, Lorentzon R, Alfredson H. Eccentric training in patients with chronic Achilles tendinosis: normalized tendon structure and decreased thickness at follow-up. Br. J Sports Med 2004;38(1):8-11.

- Jonsson P, Alfredson H, Sunding K, et al. New regiment for eccentric calf-muscle training in patients with chronic insertional Achilles tendinopathy: results of a pilot study. Br J Sports Med 2008;42(9):746-749.

- Knobloch K. Eccentric training in Achilles tendinopathy: is it harmful to tendon microcirculation? Br J Sports Med 2007;41(6):e1-e5.

- Rompe JD, Furia J, Maffulli N. Eccentric loading compared with shock wave treatment for chronic insertional Achilles tendinopathy. A randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90(1):52-61.

- Kedia M, Williams M, Jain L, et al. The effects of conventional physical therapy and eccentric strengthening for insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2014;9(4):488-487.

- Jensen MP, Chen C, Brugger AM. Interpretation of visual analog scale ratings and change scores: a reanalysis of two clinical trials of postoperative pain. J Pain 2003;4(7):407-414.

- Reddy SS, Pedowitz DI, Parekh SG, et al. Surgical treatment for chronic disease and disorders of the Achilles tendon. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009;17(1):3-14.

- Hunsberger S, Murray D, Davis CE, Fabsitz RR. Imputation strategies for missing data in a school-based multi-centre study: the Pathways study. Stat Med 2001;20(2):305-316.

- van Tetering EA, Buckley RE. Functional outcome (SF-36) of patients with displaced calcaneal fractures compared to SF-36 normative data. Foot Ankle Int 2004;25(10):733-738.

- Norregaard J, Larsen CC, Bieler T, Langberg H. Eccentric exercise in treatment of Achilles tendinopathy. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2007;17(2):133-138.

- 30. Angermann P, Hovgaard D. Chronic Achilles tendinopathy in athletic individuals: results of nonsurgical treatment. Foot Ankle Int 1999;20(5):304-306.

- Knobloch K, Kraemer R, Lichtenberg A, et al. Achilles tendon and paratendon microcirculation in midportion and insertional tendinopathy in athletes. Am J Sports Med 2006;34(1):92-97.