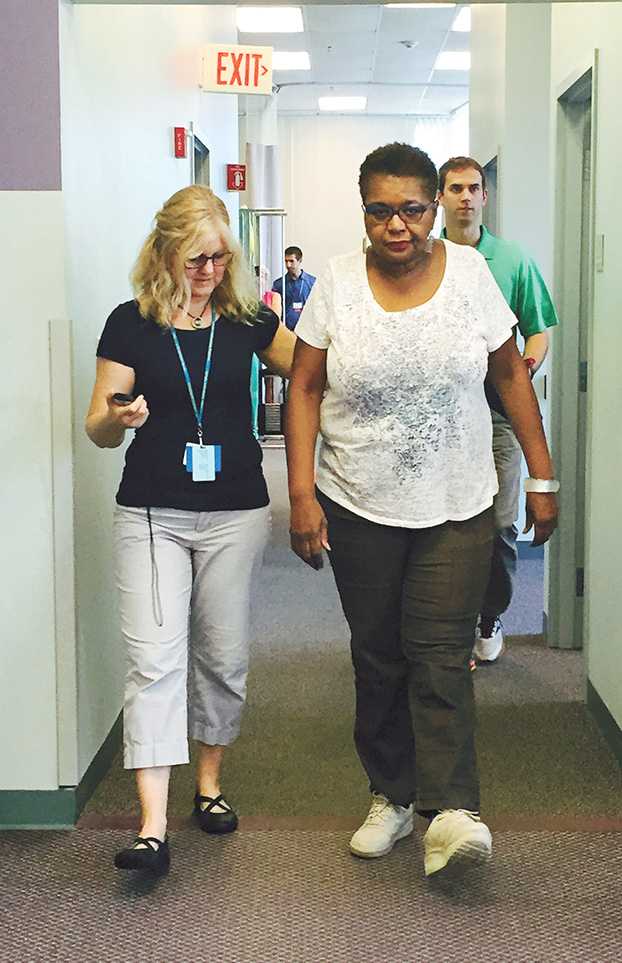

A polio survivor works with Beth Grill, PT, (left) and Nick Nappi-Kaehler, PT, (back) at the International Rehabilitation Center for Polio (IRCP) in Framingham, MA. (Photo courtesy of the IRCP.)

Along with technical issues related to muscle weakness, fatigue, and pain, the challenges of managing this heterogeneous population include patients’ emotional response to the idea of needing an orthotic device for a disability they thought they had overcome.

By Larry Hand

There are two things practitioners can agree on regarding patients with post-polio syndrome (PPS): It takes a team approach to manage these patients effectively, and each patient is truly an individual case, unlike the last and unlike the next.

“Manage” is the key word here, because no effective pharmaceutical treatment or preventive measure exists for PPS, which, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, affects 25% to 40% of polio survivors. Recent research is sparse, compared with many other disorders, so practitioners are relying largely on longstanding studies done during the 1980s and 1990s.

A key factor in managing these patients, practitioners say, is balancing any exercise or device intervention aimed at maintaining muscle strength against the risk of possibly further weakening the same muscles. Another factor is managing what many describe as a unique patient population and their muscle weakness, fatigue, and pain.

“The needs of a post-polio patient can be very diverse, as can be their willingness to accept intervention,” said Phil M. Stevens, MEd, CPO, of the Hanger Clinic in Salt Lake City. “The challenge with post-polio is that there is a lot of emotional history tied up in the individual. Most of them had to wear some type of orthopedic brace in an era when any sort of disability was poorly accepted by humanity. Many of these patients have since worked very hard to overcome and compensate for those muscle weaknesses and many of them reached a level where they can do so without braces.”

However, Stevens noted, as that generation of polio patients continues to age, those compensatory mechanisms tend to have a cumulative effect.

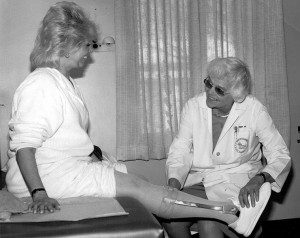

Jacquelin Perry, MD, (right) works with a polio survivor at Rancho Los Amigos Reha- bilitation Center, during the late 1980s. (Photo courtesy of Rancho Los Amigos Rehabilitation Center.)

“Many patients feel like they’ve overcome the disability of their youth and now they’re being forced to confront it again,” he said. “I have had many patients with post-polio who broke down in the treatment room because of the emotional component of getting a brace for a disability they thought they had already overcome.”

Among the recently published research papers is one from the Netherlands that illustrates the individuality of PPS patients.1 Researchers followed 48 PPS patients over 10 years to assess their rate of decline in walking capacity and physical mobility. They found that average walking capacity declined 6% and mobility declined 14% as the patients also lost an average of 15% of isometric quadriceps strength.

However, almost one fifth of the patients lost substantial walking capacity (27%) and mobility (38%), and loss of quadriceps strength accounted for only 11% of the walking capacity decline. Baseline values did not predict decline, either.

“The individual variability, yet lack of predictive factors, underscores the need for personally tailored care based on actual functional decline in patients with post-polio syndrome,” the researchers wrote.

The same group of researchers conducted another study that found ultrasound monitoring can be helpful in assessing patients’ disease severity and changes.2

Another Dutch study found that usual care trumped both exercise therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy in treating 68 PPS patients but found no explanations as to why.3

Swedish research on late effects of polio, which is closely related to PPS but had a different diagnostic code until the implementation of ICD-10 this year, has revealed risk factor variability similar to that reported in the Netherlands.

A study published in the March 2015 issue of PM&R found that knee muscle strength explained only 16% of the variance in the number of steps per day taken by 77 patients with late effects of polio, and gait performance only explained between 15% and 31% of the variance.4 A second study from the same group, published in the July 2015 issue of the Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, found that self-reported outcome measures of physical activity were only weakly to moderately correlated with self-reported disability.5

PPS patients are often highly motivated, said Beth Grill, PT, of the International Rehabilitation Center for Polio (IRCP), in Framingham, MA. But that can also end up working against them.

“Polio survivors are very independent, motivated individuals and are often described as Type A personalities. They have overcome so much in their lifetime that when they develop post-polio and they are no longer able to do the things that they have always done, it can be devastating,” Grill said.

That’s where the team approach to patient management comes in. At the IRCP, a unit of Spaulding Rehabilitation Network and Partners Healthcare system, patients see a physiatrist, a physical therapist, occupational therapist, and even a speech therapist if needed.

“Our program here at the IRCP is a comprehensive multidisciplinary program. The diagnosis of post-polio is one of exclusion. Dr. Rosenberg [Darren Rosenberg, DO], who is the medical director here at the IRCP, evaluates the polio survivor to determine what tests are needed. We not only evaluate a polio survivor’s weakness but also focus on managing pain and fatigue, which are all hallmarks of PPS. Exercise was the Holy Grail for polio survivors, and oftentimes that is what they focused on. We have to determine what exercise is appropriate and avoid over-fatiguing the muscle. If they overuse the already weakened muscles, there is potential for new weakness,” Grill said.

IRCP professionals perform a thorough manual muscle exam on every polio survivor, she said. If the strength is scored three or higher on a five-point scale (able to move the limb against gravity through the full range of motion with light resistance), they may consider an exercise intervention. If the limb is weak, however, they may recommend a lower extremity brace.

If they find no other medical causes for muscle weakness, then they begin to plan the post-polio treatment. They begin by making recommendations to the patient, and then, step by step, try to get the patient on board.

“We try to do it in a way that is respectful of where they’re at in their own process,” Grill said. “I often use the words, ‘I’m going to plant the seed. I want you to think about it. Or I want you to at least try it.’ Many people come around and are open to trying things.”

Bracing is complicated, she said, partly because it is a difficult thing for the patients to go back to, and partly because each patient presents so differently from the next in the clinic.

“Prescribing an appropriate brace and assistive device often plays a crucial role in improving gait and function for a polio survivor,” Grill said. “When we consider bracing, we try to do less than textbook bracing, because we want to be respectful of how people have learned to compensate. If you take away people’s ability to compensate, a brace may cause walking to be more work for the individual rather than less. For example, if a quadriceps muscle is very weak, and the individual has never worn a brace, we may want to give them a short-leg brace rather than a long-leg brace.”

Similarly, patients who have been diagnosed with late effects of polio need a team-based approach to treatment, said Cecilia Winberg, RPT, MSc, of Lund University in Sweden and lead author of the two Swedish studies cited earlier.

“Persons with late effects of polio perceive different kinds of impairments, and these can be treated symptomatically,” Winberg said. “The impairments have an impact on their whole life situation, which is best addressed by meeting different professionals.”

Patients with late effects of polio are best treated with an individualized physical therapy plan, since their impairments and activity limitations differ, she said.

“Most often it is important to increase muscle strength in the muscle not affected by the polio, to make sure that they can walk without too much strain [for instance, by using mobility devices and orthoses],” she said. “A PT plan is always based on a thorough examination and a discussion with the patient regarding their problems. The goals of the treatment are decided between the PT and the patient.”

Thorough evaluation

Another center that uses the team approach is Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center in California, part of the Los Angeles Health Services Department. That’s where one of the prominent researchers of the ‘80s and ‘90s worked, the late Jacquelin Perry, MD, who detailed the biomechanics involved in orthotic management of post-polio in a 1986 article in Orthotics and Prosthetics.6-9 Other studies by Perry’s group have looked at muscle tests, manual muscle testing, and calf muscle as a source of pain.

“What Dr. Perry came up with years ago, and what we still tell our patients today, is as far as exercising or activities, if they are doing some activity or exercise and when they stop they’re still just beat for more than ten or fifteen minutes, then they’ve done too much. They need to look at what they did and look at decreasing it,” said Valerie Eberly, PT, who has worked at Rancho Los Amigos for 20 years.

“Dr. Perry also said if a person has an active day and wakes up the next day completely fatigued and exhausted, that means the day before they did too much,” Eberly said. “They either have to decrease how much they do or increase the number of rest breaks they take, but they really figure out for themselves what’s the best way for them to be able to do all the things they want to do without increasing their post-polio syndrome. Bracing is not what they really want to hear, but they realize if it’s what’s needed, they’re willing to try it.”

When a person comes into the clinic for a new evaluation, he or she commonly has complaints of increasing fatigue, weakness, and pain, she said. A multidisciplinary team—including a physician, physical therapist, and occupational therapist—will perform a full evaluation, looking in particular at strength in the arms and legs.

“The physical therapist does the muscle test, and the physical therapist and the medical doctor observe the gait and look at what deviations they have. Then we, together, come up with what orthosis we think would be best for them,” Eberly explained. “We actually have an orthotist who is able to join us in our gait analysis and look at the muscle test. The orthotist will put together a temporary trial brace for the person to try. We have the patient walk with the brace in the clinic to see how it feels. We, as a team, make a recommendation of what we think would best help the patient.”

Before and after

Before the evaluation, however, comes the history.

“You need a really thorough patient history to find out what they’re doing—when did they experience the weakness and for how long—and then make recommendations to decrease the overuse of their muscles,” Eberly explained.

That’s where bracing comes in, she said.

“We recommend different types of orthoses, whether it’s an ankle foot orthosis or a knee ankle foot orthosis, to help substitute for the weak muscles and allow patients to preserve the muscles they still have,” Eberly said. “If they’ve tried all these other things and they’re still having the issue of fatigue and increasing weakness, then we would recommend a wheelchair for mobility, to allow patients to continue to participate in activities that are important to them.”

Thomas V. DiBello, CO, of Hanger Clinic in Houston, TX, wholeheartedly agrees about the importance of patient history, even at the orthosis-fitting stage.

“The most important thing the orthotist should do—and I think this is sometimes missed—is instead of reading the prescription and going to work on providing the device prescribed, the first step has to be an absolutely complete and thorough history,” DiBello said.

The orthotist should have an appreciation for any surgeries that were performed, particularly orthopedic procedures that may have occurred when the patient was a child and may have an impact on joint motion and pain.

“We need to understand the level of disability the patient had when they were younger and how that has changed, and then how their current level of ability has changed over the course of the last few years,” DiBello said. “I always like to ask what prompted them to seek care at this point in time. It’s also very important to know not just how often they fall, but how often in the course of a day or week do they nearly stumble and fall. The near falls are very important in helping us understand where that person is on their continuum of ambulation.”

Most importantly, orthotists need to know the patient’s expectations, and the expectations of the medical doctor and physical therapist treating that patient, he said.

“Then we can begin to discuss with them what we can do for them, within the parameters of the physician’s prescription and the team’s goals, and whether their expectations are achievable,” DiBello said.

Sometimes, he said, one of the biggest challenges is gaining a patient’s trust.

“Often in the past they’ve had bad experiences with devices they’ve been prescribed. They don’t always have the highest level of regard for the work we do, probably justifiably so, but there’s a period that involves them getting to know us better, as we are getting to know and understand their needs,” he added.

In addition to patient history, follow-up is also important, DiBello said. He sees patients two weeks after device fitting to assess whether they need to be seen more often than every six months to a year thereafter. Even if a patient is satisfied with a brace, there may be some adjustments that could be made to improve his or her gait, he added.

“We might adjust the amount of movement they have at the ankle, or at the knee. We might change the density of the heel portion to affect the way they transition from the beginning of stance to midstance. We might make adjustments to a lift for a leg-length discrepancy,” he explained.

Adapt and compromise

It’s always important for practitioners to have the ability to compromise, but it’s particularly true for those who work with post-polio patients, Stevens of Salt Lake City said.

“Post-polio is particularly challenging because developing a solution that is biomechanically sound isn’t enough,” Stevens said. “You have to develop a solution that a patient will accept and wear. In many cases, that involves compromise. You may not be able to use the intervention that you think is biomechanically the best approach, because the patient is unwilling to wear it. You have to reach a level of compromise where you can address some of the limitations with a device that a patient is willing to wear on a regular basis.”

Larry Hand is a freelance writer in Massachusetts.

- Bickerstaffe A, Beelen A, Nollet F. Change in physical mobility over 10 years in post-polio syndrome. Neruomuscul Disord 2015;25(3):225-230.

- Bickerstaffe A. Beelan A, Zwarts MJ, et al. Quantitative muscle ultrasound and quadriceps strength in patients with post-polio syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2015;51(1):24-29.

- Koopman FS, Voorn EL, Beelen A, et al. No reduction of severed fatigue in patients with postpolio syndrome by exercise therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy: results of an RCT. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2015 Aug 7. [Epub ahead of print]

- Winberg C, Flansbjer UB, Rimmer, JH, Lexel J. Relationship between physical activity, knee muscle strength, and gait performance in persons with late effects of polio. PMR 2015;7(3):236-244.

- Winberg C, Brohardh C, Flansbjer UB, et al. Physical activity and the association with self-reported impairments, walking limitations, fear of falling, and incidence of falls in persons with late effects of polio. J Aging Phys Act 2015;23(3):425-432.

- Clark DR, Perry J, Lunsford TR. Case studies–Orthotic management of the adult post polio patient. Orthot Prosthet 1986;40(1):43-50.

- Perry J, Weiss WB, Burnfield JM, Gronley JK, The supine hip extensor manual test: a reliability and validity study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85(8):1345-1350.

- Mulroy SJ, Lassen KD, Chambers SH, Perry J. The ability of male and female clinicians to effectively test knee extension strength using manual muscle testing. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1997;26(4):192-199.

- Perry J, Fontaine JD, Mulroy S. Findings in post-poliomyelitis syndrome. Weakness of muscle of the calf as a source of late pain and fatigue of muscles of the thigh after poliomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77(8):1148-1153.