Use the scale provided here to help you assess standing posture, including the nature and extent of deviation from normal, in children with a developmental disability.

By Dalia Zwick, PT, PHD

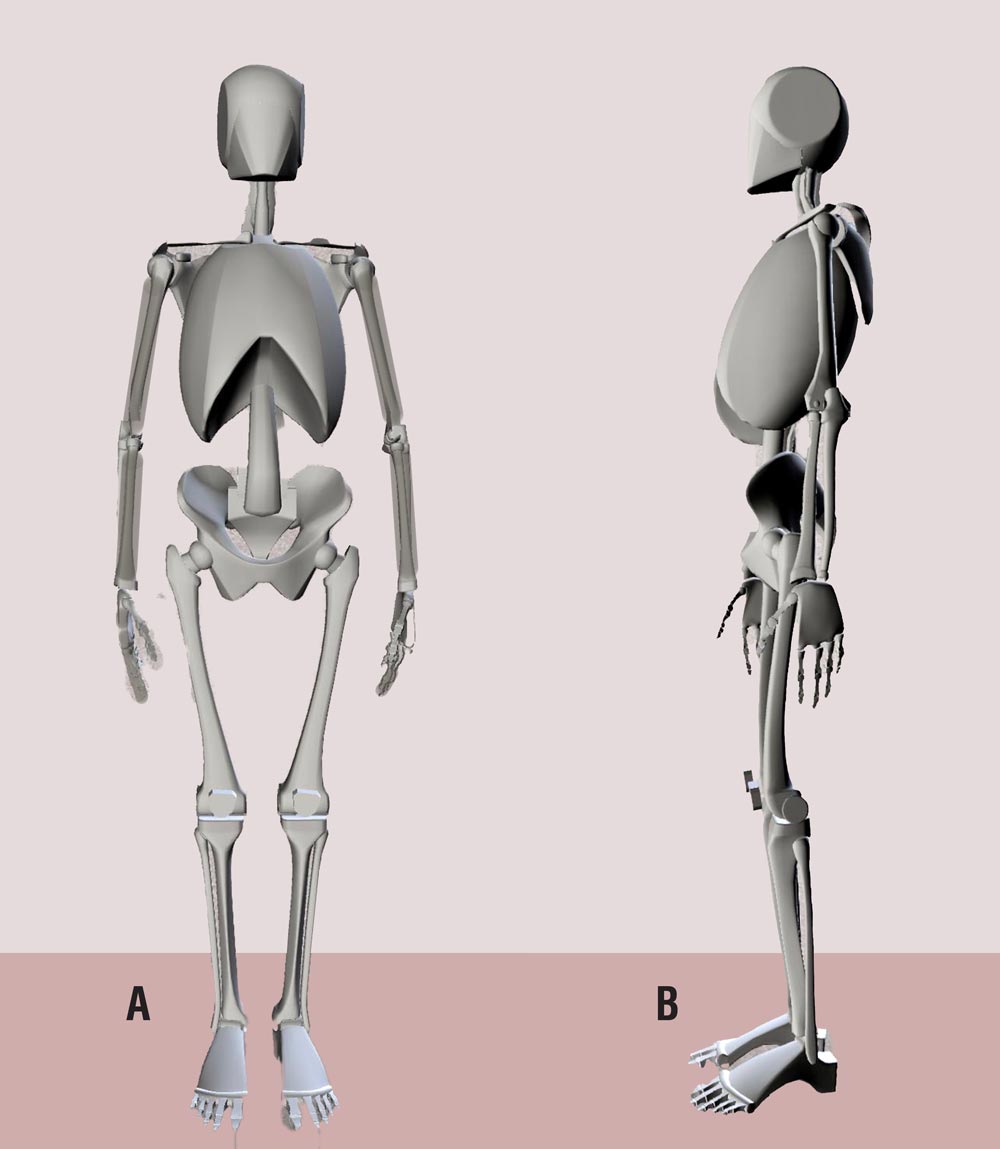

Proper standing alignment requires that muscles, bones, and joints are in correct relation to each other, creating elongation and symmetry while counteracting the detrimental force of gravity (see Figure 1).1 Stability in active standing with proper alignment requires intact neuromotor control, which is disrupted in the presence of neuromotor impairment—a problem for many children who have autism spectrum disorder (ASD).2,3

Children with ASD have a diminished perception of their body movement and postural orientation; as a result, they often sit, stand, and walk with postural impairment.4 Studies of the postural profile of children with ASD report a deviation from the typical age-matched population in regard to kyphosis, lumbar scoliosis, and genu valgum.5 This article provides a review of how to observe and record standing posture in patients with ASD.

Studies of posture in patients with ASD focus mostly on postural control and sway, not on the shape of posture itself. The design of these studies is such that subject selection often lacks information about the presence or absence of abnormalities in the shape of posture. This is regrettable, because leg-length discrepancy (LLD), scoliosis, and kyphosis are important variables in postural control (see Figure 2).

Focus Is on Posture, Which Differs From Postural Control

“Abnormal posture” is described as a treatment diagnosis, coded as R29.3 in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). Abnormal or poor posture is described as “a relationship between various body parts which may be considered as faulty and which could stretch the spectrum from the non-perfect to pathological posture. It is postulated that poor posture can produce an increased strain on the supporting structures and less-efficient balance of the body over its base of support”6 (see Figure 3).

A number of physiotherapists in the United Kingdom followed the pioneering work of Pauline Pope,7 Noreen Hare,8 and Liz Goldsmith9 who recognized the fundamental importance of learning to secure and stabilize posture’s base of support when standing, sitting, and lying as a prerequisite of functional activity. To educate caregivers and therapists about this idea, Pope and Hare advocated for analysis of the body’s ability, in regard to shape or posture. They helped design a therapeutic intervention based on the need to oppose forces of gravity by providing support to the body to stay in an elongated, symmetrical supporting surface. The idea was the groundwork for development of the Physical Ability Scale by researchers such as Teresa Pountney10 at the Chailey Heritage School (East Sussex, United Kingdom), which is now the Posture and Postural Ability Scale (see the Table, page 46).8

“Posture” and “postural ability” are terms related to, but different from, “postural control.” Postural control correlates with balance, and is the ability to maintain equilibrium and orientation in a gravitational environment.11 The Posture and Postural Ability Scale was further developed in the United Kingdom, and tested for validity in Sweden, to assess the posture of children with a developmental disability.1 On this scale, “posture” relates to the shape and gesture of the body and its relationship to the environment. “Postural ability” refers to controlling and stabilizing body segments relative to each other and to the supporting surface, in passive and active conditions.7

The Posture and Postural Ability Scale is proposed to be an aid in assessing the standing posture of children with ASD. A narrative report can be added to each item to make clear the nature and extent of the deviation in posture from normal (again, see the Table).

Issues and Evaluation of Asymmetrical Posture

Standing when the heels are raised, known as “toe-walking,” although associated with ASD in some patients, is beyond the scope of this article, which focuses on asymmetries of body shape that contribute to abnormal standing posture and are often associated with impairments in the ankle, knee, hip, and back.

Here is how adults with ASD have described their “awkward” posture12,13:

- “I have bad posture and I try very hard to hide or minimize it.”

- “I have a bad slouch/hump-back and one leg longer than the other which means one hip is a bit higher than the other.”

Indeed, a frequent treatment diagnosis of patients who have been referred to our prosthetic and orthotics clinic are abnormal posture, ankle instability, and LLD.

When visually assessing patients with ASD, we often note kyphosis, scoliosis, and asymmetrical foot deformities (see Figure 4). Furthermore, we observe that some patients sway and place more of their center of mass on a single leg. We observe standing posture while talking to the patient or caregiver and in some cases, we direct him or her to stand upright in place or near a wall.

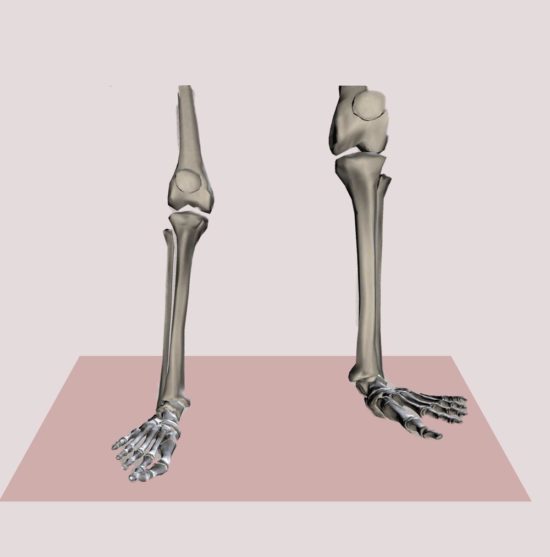

As part of assessment, we draw and make a note if a lower extremity (and which one) is habitually more engaged in carrying most of body weight (known as “engaged leg”14). We observe that some patients prefer to stand by shifting weight on a single leg when standing; some shift weight from one leg to the other; and others stand with a more even distribution of weight on both lower extremities. Patients who stand on the weight-bearing preferred leg often have LLD, ankle instability, or an asymmetrical foot deformity, such as pronation and hallux abductus valgus—phenomena that are not well-reported in medical literature (see Figure 5). The description of Trendelenburg’s sign15 fits this presentation, although the underlying diagnosis for this sign is reported as pain or weakness. And Trendelenburg’s sign is often associated with walking as opposed to standing.

Figure 4. Patients with autism spectrum disorder often have leg-length discrepancy, ankle instability, or an asymmetrical foot deformity, such as pronation and hallux abductus valgus.

An interesting depiction of standing upright with one leg engaged and the other flexed and relaxed is common in the visual arts (painting and sculpture). There, the term contrapposto is often used to describe asymmetry in modeling:

It [contrapposto] is used in the visual arts to describe a human figure standing with most of its weight on one foot so that its shoulders and arms twist off-axis from the hips and legs in the axial plane. In the frontal plane this also results in opposite levels of shoulders and hips, for example: if the right hip is higher than the left; correspondingly the right shoulder will be lower than the left, and vice versa.14

Patients with ASD who have reduced neuromotor postural control tend to stay in the asymmetric posture of contrapposto, unknowingly neglecting the sensory signal of pain or discomfort. They often stay in this asymmetrical posture, shifting weight onto one leg—habitually, the preferred leg. Short-term consequences of this asymmetric posture include behavioral issues; fatigue; awkwardness; clumsiness of one or both feet; and instability of the ankle, knee, hip or spine. Long-term effects are hip migration or dislocation, LLD, and, at a later stage, reduction in or loss of the ability to walk.

Yoga, Physical Therapy, and Orthotics in the Management Plan

In assessing the standing posture of patients with a development disability, it becomes clear that foot and ankle problems are often interrelated—affecting, and being affected by, overall body posture.

Yoga. There is a role for exercises based on yoga, particularly the Iyengar method, when devising a therapeutic approach to these problems, to improve symmetry in standing posture. Iyengar yoga considers standing postures to be the foundation of other yoga asanas (postures). Practicing standing poses, such as a tree or mountain pose, and even wide-legged standing with foot/ankle in neural position with big toe pointing forward teaches the student–patient to engage gravity by working on awareness in active symmetrical standing with contracting muscles of lower extremities in extension, abduction, adduction, and rotation.16

Why Are AFOs Important in ASD?

An ankle–foot orthosis helps keep the foot in a neutral position and prevents deformities. It increases the base of support and provide stability in standing positions. At times, there is a need to provide better support for children with ASD; for this purpose, an ankle–foot orthosis stabilizes the joint and prevents excessive range of motion.1

Source: Wingstrand M, Hägglund G, Rodby-Bousquet E. Ankle–foot orthoses in children with cerebral palsy: a cross sectional population based study of 2200 children. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:327.

Physical Therapy, with focus on posture and alignment, can help improve awareness of even weight distribution and a correct alignment of the leg in all 3 planes of motion. Therapists who are also a yoga practitioner by themselves will probably be better at directing the patient in correct alignment from the foot up.

Orthotics. An approach that includes yoga should be integrated with orthotics to improve ankle and foot stability (see “Why are AFOs important in ASD?,” page 46) and, when needed, shoes and shoe lifts. Assessment of the foot/ankle complex and relating it to the whole body posture will determine the type of brace or custom orthosis to be used. Lift for the short leg seems like the easy solution or panacea and should be considered only after some further intervention. If a lift is added and the patient is not trained in shifting weight to the other leg, he or she will continue to lean onto the short leg; with added lift, he or she will hike the pelvis of the engaged leg, contributing to further body distortions.

Dalia Zwick, PT, PhD, is Clinical Supervisor and Physical Therapist, Young Adult Institute (YAI) Network’s Premier HealthCare and YAI Center for Specialty Therapy, Brooklyn, New York. Contact her at Dalia.Zwick@yai.org.

- Rodby-Bousquet E, Agústsson A, Jónsdóttir G, Czuba T, Johansson A-C, Hägglund G. Interrater reliability and construct validity of the Posture and Postural Ability Scale inadults with cerebral palsy in supine, prone, sitting and standing positions. Clin Rehabil. 2014;28(1):82-90.

- Chen L-C, Su W-C, Ho T-L, et al. Postural control and interceptive skills in children with autism spectrum disorder. Phys Ther. 2019;99(9):1231-1241.

- Mosconi MW, Wang Z, Schmitt LM, Tsai P, Sweeney JA. The role of cerebellar circuitry alterations in the pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorders. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:296.

- Lim YH, Partridge K, Girdler S, Morris SL. Standing postural control in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(7):2238-2253.

- Postural profile in children with autism Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences.Sharif HN, Daneshmandi H, Norasteh AA, Aboutalebi S. Postural profile in children with autism. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2016;26(143):71-79.

- Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG, Rodgers M, Romani WA. Muscle Testing and Function With Posture and Pain, ed 5. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- Pope PM. Severe and Complex Neurological Disability: Management of the Physical Condition. Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann Elsevier; 2007.

- Nichols C, Pope P, Linda Whitaker L. Tribute to Noreen Hare. Association of Paediatric Charted Physiotherapists Journal. 2017;(122)38-39.

- Mencap: The voice of learning disability. Mencap.org.uk. Accessed March 4, 2020.

- Pountney, TE, Cheek, L, Green, E, Mulcahy, C, Nelham, R. Content and criterion validation of the Chailey levels of ability. Physiotherapy. 1999;85(8):410–416.

- St George RJ, Gurfinkel VS, Kraakevik J, Nutt JG, Horak FB. Case studies in neuroscience: a dissociation of balance and posture demonstrated by camptocormia. J Neurophysiol. 2018;119(1):33-38.

- Worrying too much about your posture is bad posture. Wrong Planet Web site. https://wrongplanet.net/forums/viewtopic.php?t=358791. Accessed February 15, 2020.

- Who else here has back problems/pain? Wrong Planet Web site. https://wrongplanet.net/forums/viewtopic.php?t=264918. Accessed February 15, 2020.

- Contrapposto. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contrapposto. Accessed February 15, 2020.

- Trendelenburg’s sign. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trendelenburg%27s_sign. Accessed February 15, 2020.

- Wang S-J. Foundation of Iyengar yoga: standing poses. Seattle Iyengar Yoga Studio Web site. https://seattleiyengaryoga.com/2014/10/27/foundation-iyengar-yoga-standing-poses/. Accessed February 15, 2020.