By Hank Black

By Hank Black

Healthcare education materials for patients are consistently written at a reading level too advanced for a significant number of people–a trend that affects all aspects of lower extremity care and can adversely affect clinical outcomes. Some organizations are starting to make health literacy a priority, but that’s much easier said than done.

In 1994, researchers analyzed the readability of educational material about prosthetics and found that only four of 32 samples scored at a level considered understandable by most consumers.1 Since then, multiple studies of materials produced by other lower extremity healthcare organizations have reached a similar conclusion: A substantial wedge of the population pie has considerable difficulty comprehending much of the educational material available to them.

Low health literacy affects some 80 million Americans.2 Compared with the general population, they have more difficulty communicating with clinicians, more barriers to managing chronic illness, a lower likelihood of receiving preventive care, a greater likelihood of having serious medication-related mistakes, increased chances of hospitalization, poorer quality of life, and shorter survival.2 Williams et al found that 21% of public hospital patients surveyed could not read instructions on a fourth-grade level.3

Health literacy includes a range of skills that individuals need to function effectively in a healthcare environment. Once defined primarily in terms of reading ability, health literacy now can encompass many other skills, including Internet navigation.4 There are many definitions, but an inclusive one is incorporated in the Calgary Charter on Health Literacy: “Health literacy allows the public and personnel working in all health-related contexts to find, understand, evaluate, communicate, and use information. Health literacy is the use of a wide range of skills that improve the ability of people to act on information in order to live healthier lives. These skills include reading, writing, listening, speaking, numeracy, and critical analysis, as well as communication and interaction skills.”5

Limited health literacy disproportionally affects not only those with little or no education, but also the elderly, ethnic minorities, disabled individuals, people with low socioeconomic status, and those without proficiency in the primary language of their residence.6

And, for people with chronic and complex lower extremity conditions that require a higher level of self-management—type 2 diabetes, for example—the inability to find, understand, and act on information can seriously hamper their ability to be active partners in many aspects of their own care.7

Another study of O&P educational materials’ readability was published in 2009.8 Senior author George W. Brindley, MD, professor and chair of the Department of Orthopedic Surgery and Rehabilitation at Texas Tech Health Science Center in Lubbock, said the materials on average were written at a 12th-grade reading level.

“To improve healthcare outcomes, there needs to be access to appropriate information for everyone, including videos in the clinic setting or even a reading list or website for viewing,” Brindley said. “It would also be helpful to require patient participation in classes, physical therapy, and home preparation prior to elective surgery.”

Michael J. Highsmith, PhD, DPT, CP, FAAOP, president of the American Academy of Orthotics and Prosthetics (AAOP), acknowledged the growing importance of health literacy.

“There is more emphasis today on health literacy, and we need to continue to shine a light on it and make sure that our instructional and other material is presented in a way the patients can understand and act on,” Highsmith said. “A person with a new amputation of a leg shouldn’t be expected to retain all of the verbal instructions provided to them in that kind of stressful and acute healthcare situation. Their lack of comprehension during this very busy period could lead to a degree of skin breakdown and discomfort that could cause the patient to disuse or reject their prosthetic device. It is for this reason that the academy is focusing on health literacy.”

Now a high priority

Yet the AAOP and other organizations acknowledge that, despite the best of intentions, health literacy is continually in danger of being pushed down their priority lists.

Yet the AAOP and other organizations acknowledge that, despite the best of intentions, health literacy is continually in danger of being pushed down their priority lists.

“An update of our website, and both our consumer and professional literature, will be discussed at our strategic planning session,” Highsmith said. “It’s obvious that this will require additional resources in finances and time, but I am hopeful it will maintain its high priority position.”

The popularity of the Internet has created a surge in the amount of material available to consumers.9 A 2014 survey conducted by the Pew Internet Project found that 87% of adults in the US use the Internet (58% own a smartphone), and 72% of Internet users say they looked online for health information within the past year.10 About 14% do not have the basic health literacy skills to navigate their health issues.11

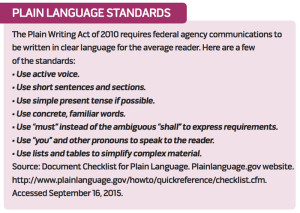

The average US adult reads at the eighth-grade level,12,13 and fourth-grade text is difficult to comprehend for one in five US adults.9 National organizations such as the American Medical Association (AMA) and the National Institutes of Health say patient education materials should aim for a sixth-grade readability level.11

Recent studies indicating that patient education materials are of poor quality, or written at a reading level too advanced for many to understand, have focused on materials created by medical specialty groups as well as condition-specific material that a consumer might find in an Internet search. Agarwal et al14 analyzed the quality of patient education materials from 16 professional medical organizations and found that none met the recommended sixth-grade maximum readability level—or even the seventh- to eighth-grade reading ability of the typical American adult. By one measure, one specialty group’s material was unclassifiable because its complexity was beyond the graduate school level.

Most organizations have acknowledged the problem and made varying efforts to improve their materials. E. Anne Reicherter, PT, DPT, coauthored a 2008 analysis of the website of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) and calculated that at least 85% of the 14 online brochures reviewed were written at a reading level higher than sixth grade.15 Reicherter, now a senior practice specialist at the APTA, said that the organization has addressed those problems through its official consumer information website, MoveForwardPT.com. A review process now ensures the site meets healthy literacy standards, including better design as well as linguistic readability, she said.

“Better design is now considered part of health literacy because it makes text easier to read and the website easier to navigate,” she said. “Things like contrasting colors and larger type take into account the aging vision of the older patient demographic.”

“Better design is now considered part of health literacy because it makes text easier to read and the website easier to navigate,” she said. “Things like contrasting colors and larger type take into account the aging vision of the older patient demographic.”

Some experts have difficulty believing complex material can be written simply and still maintain its quality. Although the APTA has not formally reassessed the readability of its materials, Reicherter acknowledged that current APTA consumer material is geared to ninth-grade readability.

“It’s difficult to condense complex medical topics and terminology into two-syllable words, which helps with readers at a sixth-grade reading level,” she said. “We try to include more definitions and explanations in place of medical lingo. It’s an ongoing effort.”

Online patient education materials available from multiple orthopedic surgery websites frequently exceeded recommended readability levels in published studies.11,16,17 Feghhi et al found the current American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons website materials have improved since a 2007 analysis but are still above the average US adult reading level.18

Brett Owens, MD, chair of the publications committee of the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, said writing below the eighth-grade level is a challenge for medical professionals.

“We try to be the storehouse of information that people can trust, so the quality of the content is highly important to us,” Owens said. “And sometimes going too low in literacy level seems to dilute the quality.”

To help deal with low health literacy, Owens, a professor of orthopedic surgery at Brown University in Providence, RI, said clinicians might suggest patients be accompanied by a relative or friend to help them understand verbal as well as written explanations and instructions.

“We also can use vetted models, illustrations, and especially videos right there in the clinic to back up our conversations with patients,” he said.

A 2014 publication by Sheppard et al noted that limiting sentences to 15 words or fewer lowered the reading levels of most foot and ankle patient education literature by an average of 1.41 grade levels per article. It also recommended providing simple, stepwise instructions to those writing such articles.19

For several years the Amputee Coalition, a consumer advocacy and patient education organization, produced two different sets of informational material, one called EasyRead, with text at a sixth-grade level, the other at a more typical 10th-grade level.

“The effort was abandoned a couple of years ago after an analysis that showed the EasyRead material was not being used as much as we thought it should be,” said George C. Gondo, MA, of Knoxville, TN, director of research and grants for the group. “It turns out that people don’t like to think of themselves as having low reading skills.”

The coalition attempts to produce material at about the eighth-grade level of reading.

“We wind up being closer to the ninth-grade level,” Gondo said. “This is a complex field with many technical terms, and it can be difficult to get patient education materials about prosthetic devices down to a lower reading level. We feel it does consumers a disservice if we don’t use terms they will likely encounter in their interactions with healthcare providers. But if we use a technical term, we will immediately define it in an understandable way.”

The Amputee Coalition and other organizations use an advisory board of consumers and professionals to help ensure the materials are accessible to patients and include quality information.

Jeffrey D. Lehrman, DPM, who has a podiatry practice in Springfield, PA, pointed out that patients searching the Internet for information on a health matter often find inaccurate or misleading material.

“Forums and chat rooms are highly anecdotal and not based on evidence, so I emphasize the importance of practitioners putting out high-quality information on our own websites and through social media,” Lehrman said. “It’s not only powerful marketing, but it also gives us the opportunity to put correct information out there in terms patients can understand. Remember that a patient will search for ‘bunion’ or ‘big toe joint pain’ rather than ‘hallux valgus.’”

Lehrman recently presented the American Podiatric Medical Association’s first session on how to communicate information to patients using the Internet and social media. He said such sessions that include health literacy recommendations are attracting more attention among his colleagues, though he noted that some organizations question whether the subject deserves to receive continuing education credits.

“I argue that the doctor has the responsibility to provide good information using the technology we did not have twenty years ago,” Lerhman said. “You can hand an instructional sheet to one person, but putting it on the web can reach many thousands of people.”

The ‘art’ of communicating

One 2015 publication identified 43 different instruments for measuring health literacy.20 Some methods can take an hour to administer and are best suited for researchers. Others can be administered in less than five minutes and, therefore, are more likely to be used in clinical settings. The latter category includes the Revised Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM-R),21 the Test of Functional Health Literacy for Adults (TOFHLA),22 the SMOG (Simplified Measure of Gobbledygoop) Readability Calculator,23 and the Newest Vital Sign (NVS).24 Duell et al determined that the NVS is the most practical instrument to use quickly in a clinical setting, but also called for the development of a more encompassing instrument that would be applicable in the clinic as well as in general health promotion.20

Yet, due to limitations on their time, most practitioners have grown used to assessing patients’ health literacy level informally and quickly as they initiate the clinic visit and take a history and physical.

“It’s hard to say exactly how to solicit a person’s level of health literacy, partly because it’s part of the art of the doctor-patient interaction,” Owens said.

Determining a patient’s level of understanding is a constant challenge, said Amy Darragh, PhD, OTR/L, FAOTA, associate professor of occupational therapy at Ohio State University in Columbus.

“People desire different types of information from healthcare providers,” Darragh said. “While there are measures available to assess whether someone can take their medications and understand some jargon, we need to develop a method to assess other skills, for example, their ability to synthesize information from multiple healthcare providers and use it to manage their own care.”

Darragh also wants to see the healthcare field provide leadership in helping families and individuals learn how to search the Internet for science-based information.

Coping with low health literacy

In three 2010 studies of material given to parents with children in early intervention, Kris Pizur-Barnekow, PhD, OTR/L, found that critical information was often inaccessible to families with low health literacy levels.25-27

“However, if people with low health literacy can be taught strategies, such as bringing along someone to help, or adaptive mechanisms to use that are as simple as putting the medication schedule on the refrigerator, they can manage their care better,” said Pizur-Barnekow, an associate professor of occupational therapy at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

To help determine a patient’s health literacy and find ways to communicate at that level, Pizur-Barnekow, Lehrman, and others recommend use of communications toolkits available from organizations such as the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS),28 the AMA,29 and the American Diabetes Association.30

Several experts cited the teach-back method found in the toolkits as a common strategy for determining how well patients understand what they are told. This method has the clinician ask a patient to explain or demonstrate what he or she has just heard.

“It’s humbling to realize how little some patients can repeat,” Lehrman said. “That’s something of an indictment of our communication skills.”

Lower limb practitioners concerned about whether a patient comprehends instructions but with too little time to assess their health literacy may refer patients to diabetes educators or other allied health professionals who are trained in health literacy assessment, said Kellie Antinori-Lent, MSN, RN, ACNS-BC, BC-ADM, CDE, a diabetes educator and clinical nurse specialist at UPMC Shadyside Hospital in Pittsburgh, PA.

“Diabetes educators have the time, clinical knowledge, and skill set to educate and support patients in all their care and self-management issues, including health literacy,” Antinori-Lent said.

Health literacy training can help ensure patients with diabetes understand the importance of foot self-examinations and other aspects of self-care, she said.

Health literacy training can help ensure patients with diabetes understand the importance of foot self-examinations and other aspects of self-care, she said.

“We have them repeat back the steps and perhaps demonstrate how they check their foot, and emphasize that they must remember and incorporate that into their everyday routine,” Antinori-Lent said. “We have to be sure that the wound won’t worsen under self-management.”

Making sure the patient understands written and verbal instructions was not part of the conversation in some fields until recent years. Today, it’s an accreditation standard and an important part of the curriculum in several areas of study, including physical therapy and occupational therapy.

“It’s our responsibility to help students understand how important it is and that physicians and clients expect that of us now,” Pizur-Barnekow said.

A systems approach

Historically, health literacy was viewed as a trait of the individual consumer, but it has broadened to include healthcare professionals and health systems, said Terri Ann Parnell, MA, DNP, RN, of Garden City, NY. Formerly the vice president for health literacy and patient education for the North Shore LIJ Health System in New York, Parnell is principal and founder of Health Literacy Partners and a member of the Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Health Literacy.

“The biggest shift today is that organizations [such as health systems] are trying to embed health literacy as an organizational value, creating a culture that doesn’t treat it as a one-off program,” she said.

Brindley of Texas Tech said, “Health literacy is becoming more of a priority to hospitals and clinics. Some now even require patients to go to a class that discusses expectations of and how to prepare for elective surgery.”

So the question remains: Is health literacy, maturing as a field, poised to become the norm?

“We are still a good bit away from having enough people in healthcare who ‘get it’ about how important health literacy is to patient care and satisfaction,” Lehrman said. “But we are coming to believe. We’re definitely getting there.”

Hank Black is a medical writer in Birmingham, AL.

- Guide to Health Literacy and Older Adults. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website. http://health.gov/communication/literacy/olderadults/literacy.htm. Accessed September 9, 2015.

- AHRQ (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) Health Literacy Interventions and Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcsums/litupsum.htm. Published December 2014. Accessed September 9, 2015.

- Williams MV, Parker RM, Baker DW, et al. Inadequate functional health literacy among patients at two public hospitals. JAMA 1995;274(21):1677-1682.

- Pleasant A. Advancing health literacy measurement: A pathway to better health and health system performance. J Health Commun 2014;19(12):1481-1496.

- The Calgary Charter on Health Literacy. The Calgary Institute on Health Literacy Curricula. The Centre for Literacy website. http://www.centreforliteracy.qc.ca/sites/default/files/CFL_Calgary_Charter_2011.pdf. Published October 2008. September 9, 2015.

- National Center for Education Statistics. The Health Literacy of America’s Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education; 2006.

- Williams MV, Baker DW, Parker R, et al. Relationship of functional health literacy to patients’ knowledge of their chronic disease: a study of patients with hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med 1998;158(2):166-172.

- Hrnack SA, Elmore SP, Brindley GW. Literacy and patient information in the amputee population. J Prosth Orthot 2009;21(4):223-226.

- Badarudeen S, Sabharwal S. Readability of patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America web sites. J Bone Joint Surgery Am 2008;90(1):199-204.

- Fox S, Duggan M. Pew Research Center Health Online 2013. PewResearchCenter website. http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/01/15/health-online-2013/. Published January 15, 2013. September 9, 2015.

- Eltorai AE, Han A, Truntzer J, et al. Readability of patient education materials on the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine website. Phys Sportsmed 2014;42(4):125-130.

- Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. Second ed. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott; 1996.

- Albright J, de Guzman C, Acebo P, et al. Readability of patient education materials: implications for clinical practice. Appl Nurs Res 1996;9(3):139-143.

- Agarwal N, Hansberry DR, Sabourin V, et al. A comparative analysis of the quality of patient education materials from medical specialties. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(13):1257-1259.

- Falconer N, Reicherter EA, Billek-Sawhney B, et al. An analysis of the readability of educational materials on the consumer webpage of a health professional organization: considerations for practice. Internet Journal of Allied Health Science and Practice. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract 2011;9(3).

- Bluman EM, Foley RP, Chiodo CP. Readability of the patient education section of the AOFAS website. Foot Ankle Int 2009;30(4):287-291.

- Eltorai AE, Sharma P, Wang Jing, et al. Most American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons’ online patient education material exceeds average patient reading level. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015;473(4):1181-1186.

- Feghhi DP, Agarwal N, Hansberry DR, et al. Critical review of patient education materials from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Am J Orthop 2014;43(8):E168-E174.

- Sheppard ED, Hyde Z, Florence MN, et al. Improving the readability of online foot and ankle patient education materials. Foot Ankle Int 2014;35(12):1282-1286.

- Duell P, Wright D, Renzaho AM, Bhattacharya D. Optimal health literacy measurement for the clinical setting: A systematic review. Patient Educ Counsel 2015 Apr 25. [Epub ahead of print]

- Bass PF 3rd, Wilson JF, Griffith CH. A shortened instrument for literacy screening. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18(12):1036-1038.

- Parker R, Baker D, Williams M, et al. The test of functional health literacy in adults: A new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med 1995;10(10):537-541.

- McLaughlin GH. SMOG grading–a new readability formula. J Reading 1969;12(8):639-646.

- Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med 2005;3(6):514-522.

- Pizur-Barnekow K, Patrick T, Rhyner PM, et al. Readability of early intervention program literature. Topics Early Child Special Ed 2011;31(1):58-64.

- Pizur-Barnekow K, Doering J, Cashin S, et al. Functional health literacy and mental health in urban and rural mothers of children enrolled in early intervention programs. Infants Young Children 2010;23(1):42-51.

- Pizur-Barnekow K, Patrick T, Rhyner PM, et al. Readability levels of individualized family service plans. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 2010;30(3):248-258.

- Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) Health literacy universal precautions toolkit [AHRQ publication no. 10-0046-EF]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resources/tools/literacy-toolkit/healthliteracytoolkit.pdf. Acessed September 9, 2015.

- Wolff K, Cavanaugh K, Malone R, et al. Health literacy: a manual for clinicians. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association Foundation; 2007.

- The Diabetes Literacy and Numeracy Education Toolkit (DLNET): materials to facilitate diabetes education and management in patients with low literacy and numeracy skills. Diabetes Educ 2009;35(2):233-236.