At the Shelbourne Knee Center, there’s no set time line for return to sports after ACL reconstruction. Instead, return to play is based on range of motion and strength goals, achieved through a rehabilitation protocol that is set in motion even before surgery.

By Scott E. Urch, MD, K. Donald Shelbourne, MD, and Heather Freeman, PT, DHS

Many advances have been made in the treatment of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears over the last several decades, and research continues to evolve. Because of the innovations in surgical techniques and rehabilitation, an ACL tear is no longer considered the devastating, career-ending injury that it once was.

When athletes sustain an ACL tear, the first question they have is usually, “When will I be able to play sports again?” Although this issue tends to be at the forefront of an athlete’s mind at the time of injury, they also value the importance of achieving a good long-term result that will allow them to function at a high level throughout their lifetime. As orthopedic practitioners, our primary responsibility is to ensure a good long-term outcome after ACL reconstruction. Secondarily, we strive toward a quick, but safe, return to sports. We recently conducted a study to examine specifically the teenage athlete’s ability to return to competitive sports after ACL reconstruction. The findings from this research and from our long-term ACL follow-up data are discussed in this article.

By tracking our outcomes after ACL reconstruction for more than 25 years, we have identified the factors associated with a successful long-term result.1,2 Based on this information, we have made modifications to our perioperative rehabilitation program in an effort to improve the long-term outcomes of the procedure and allow for a faster recovery process. As we improved the rehabilitation and patients began reaching their therapy goals more quickly, we began asking ourselves, “If the knee is stable with full range of motion (ROM) and strength levels are symmetric to the opposite side, is there a time that is too soon to allow an athlete to return to competitive sports?”

A widely accepted guideline in the orthopedic community is that return to full sports competition should not be permitted until six months after an ACL reconstruction; however, a range between 4.1 to 8.1 months for return to sports has been reported.3-6 Many of our patients were meeting the goals for rehabilitation and were comfortable with low-level sports activities as early as two months after ACL reconstruction. Without specific data from clinical studies to justify waiting until after six months, we began allowing athletes to return to sports based on a goal-specific, return-to-sport guideline rather than a time-specific guideline. After meeting the goals of eliminating the effusion, regaining full, symmetric range of motion, and regaining symmetric quadriceps muscle strength compared to the opposite knee, athletes were permitted to begin a functional progression back into sports activities as soon as they felt comfortable.

Previous studies have reported the rate of return to the same level of sport activity after ACL reconstruction to be between 26% and 97%.2-5,7-15 Many of these studies included patients of varying ages and activity levels,2,3,5,7-11,13-15 making it difficult to determine the rate of return to competitive sports alone. Furthermore, it is thought that female athletes may not return to sports as quickly or as often as male athletes16 and may require more rehabilitation visits than male athletes.17

Data collection

Patients who undergo ACL reconstruction at our clinic are enrolled into a prospective long-term outcome study to evaluate objective and subjective results, including the ability of athletes to return to competition after ACL reconstruction. As part of the data collection, patients complete postoperative surveys to determine when they are able to return to low-level sporting activity (such as shooting baskets, individual agility drills, or individual ball handling drills), and when they are able to return to full sports competition at full capability. Any additional injuries to either knee are recorded prospectively to analyze whether returning to competition quickly after ACL reconstruction increases the risk for re-injury.

Return-to-play results

The specific results for boys and girls who play basketball and soccer in school-age sports were reported by Shelbourne et al.18 This review includes the data reported previously18 along with additional data for school-age athletes in volleyball, gymnastics and football.

We evaluated 604 patients under the age of 17 who were competitive high school athletes in the following sports: basketball, soccer, volleyball, gymnastics, and football. These sports were selected for this study because they are known to be associated with a high risk for injury to the ACL.4 We limited the study population to athletes who were 17 years old or younger because this would ensure that the athletes had at least one year of high school athletics ahead of them and we could accurately evaluate their ability to return to the same level of sports. Any subsequent injuries to either knee were recorded regardless of whether they occurred during the first postoperative year or at a later date.

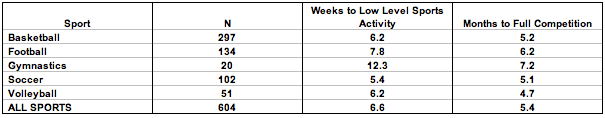

Overall, 95% of the athletes in this study returned to competitive high school athletics. The percentage of athletes who returned to their same sport at the same competitive level was 86% for girls and 81% for boys. Athletes returned to low-level sporting activity at a mean of 6.6 weeks, and the mean time to return to full sports competition was 5.4 months (Table 1). When looking at the sports that have equal participation between boys and girls (basketball and soccer), there was no significant difference in the ability or time to return to full competition based on sex (p =.30).

Another interesting finding was that 25% of the athletes included in this study went on to compete in collegiate athletics. This percentage is much higher than the national averages of 3% to 6% reported by the NCAA19 for the sports in this study. These data indicate that the athletes in this study not only returned to sports quickly, but were able to return to playing at a high level of skill and remained competitive with their peers. This higher average may also be a reflection of the level of intensity and aggressiveness of athletes who tear their ACL.

Subsequent injury results

This study specifically examined the ability to return to sports after ACL reconstruction in high school-aged competitive athletes who participate in sports that are known for a high risk of ACL tear. Another study by Shelbourne et al20 evaluated subsequent injury rates for all age groups across all activity levels. The injury rate to the ACL-reconstructed knee within five years after surgery for patients younger than 18 was 8.7%, but the re-injury rate dropped significantly to 2.6% for patients 18-25 years of age and to 1.1% for patients above the age of 25. Of note is that the ACL injury rate to the opposite knee was 8.7% for patients younger than 18, 4.0% for patients 18-25 years old, and 2.8% for patients older than 25.

Overall, the incidence of subsequent injuries was lower for the ACL-reconstructed knee (4.3%) compared to the opposite knee (5.3%).20 This was especially true among female patients (Table 2). We believe this difference can be attributed to the size of the ligament. Several studies have found that women have smaller ACLs than men.21-23 An MRI study found the mean width of the ACL to be 5.7 ± 1.1 mm for women and 7.1 ± 1.2 mm for men.22 In our study, all patients received a 10 mm wide patellar tendon graft for ACL reconstruction; therefore, on average the ACL graft is significantly larger than a man’s native ACL and nearly twice the size of a woman’s native ACL in the contralateral normal knee. Although hormone levels and landing techniques have been suggested as possible reasons for ACL tears in women,24 these factors remain present after surgery. The smaller native ligament in the opposite knee is an identifiable difference that may account for the different subsequent injury rates between the ACL-reconstructed knee and the opposite knee.

The higher rate of subsequent injury correlates with younger age because the younger population is more commonly involved in high-risk sports participation on a regular basis. As people become older, they are less likely to participate on a regular basis in competitive sports that are associated with a high risk for ACL tears. Therefore, the 604 high school-aged competitive athletes included in this study represented the highest risk group for ACL tears due to their young age and participation in high risk sports.

Shelbourne et al found that overall, the mean time of subsequent injury to either knee was 19 months after surgery for the ACL-reconstructed knee and 28 months for the opposite knee.20 In the group of high school competitive athletes, 432 athletes (72%) returned to full sports competition between two and six months after surgery (early group) and 172 (28%) returned to sports after six months (late group). To determine whether early return to sports increased the risk for re-injury, we compared the incidence of early (within one year) graft tears in the ACL-reconstructed knee between the early return to sport group and late group. The rate of re-injury was 4.9% for athletes who returned to sports early, and this was not significantly different than the re-injury rate of 4.7% for athletes who returned late (p = .9133). The study by Shelbourne et al20 also found that the time of return to full sports was not a factor for re-injury among patients of all age groups and activity levels. These results indicate that the timing of return to sports does not influence the rate of subsequent injury.

Long-term outcome

The desire to return to sports as quickly as possible should not outweigh the importance of ensuring a good long-term outcome. The previous study by Shelbourne and Gray1 studied the results of ACL reconstruction at a minimum of 10 years after surgery and specifically evaluated how the loss of normal knee range of motion after ACL surgery affected the results. Normal knee range of motion was defined according to the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) objective criteria as within 2° of extension (including hyperextension) and 5° of flexion compared with the uninvolved knee.

The study group consisted of 1276 patients (357 women and 919 men). Minimum 10-year objective follow-up was obtained on 502 patients, while subjective follow-up was obtained for 1113 patients. There were no statistically significant differences in the IKDC survey scores between the objective follow-up group and the patients with subjective follow-up only. A regression analysis showed that a lack of normal knee extension was the most statistically significant factor related to lower subjective scores. Loss of normal knee flexion was also a significant factor related to lower subjective scores. Patients who had meniscectomy or articular cartilage damage at the time of their ACL reconstruction had significantly lower subjective scores if they also had less than normal range of motion.

A minimum of 10 years after ACL reconstruction, 66% of patients were still participating in sports involving jumping, pivoting, and twisting at least at a recreational level; and 27% of patients were still participating in lower-level sports that do not involve jumping, pivoting, and twisting. Therefore, most patients were able to participate in sports activities at least 10 years after their ACL reconstruction and the level of functioning, as measured by subjective surveys, was directly related to achieving normal range of motion after surgery.

Perioperative treatment program

All of the 604 high school-aged athletes in this study underwent ACL reconstruction using a patellar tendon autograft harvested from either the ipsilateral or contralateral knee. By continually looking at our outcome data for ACL reconstruction, we have refined the methods used in perioperative management of these patients to increase the speed of recovery and improve the long-term results.

First, we learned that performing acute ACL reconstructions is associated with a higher risk of ROM complications;25 therefore, we no longer perform any ACL reconstructions acutely. Instead, a preoperative rehabilitation program is initiated immediately after the ACL injury to focus on reducing the effusion, obtaining full terminal knee extension compared to the opposite knee, and regaining full flexion prior to surgery. Once these goals have been met, the knee is restored to a quiescent state after the injury and is better prepared for ACL reconstruction. Achieving these goals pre-operatively allows for a faster recovery and significantly reduces the rate of arthrofibrosis after ACL reconstruction.25 This also gives the patient time to prepare mentally for the surgery and make arrangements for appropriate care and time off from school or work after the surgery.

Second, we have learned that it is counterproductive to work on ROM and strengthening at the same time after ACL reconstruction surgery when ipsilateral grafts have been used. The early phase of rehabilitation needs to focus on ROM and swelling control in the ACL-reconstructed knee. Specifically, the early rehabilitation focuses on maintaining full terminal hyperextension compared to the opposite knee and improving flexion until it is symmetrical to the opposite knee. Once these goals are achieved, the patient may begin to work on quadriceps muscle strengthening to rehabilitate the donor site. However, it is important that strengthening does not occur at the expense of ROM loss. Patients must continually monitor their ROM and reduce the intensity and frequency of strengthening exercises if ROM decreases.

When a contralateral graft is used, this process is accelerated because the patient is able to split these competing rehabilitation goals between the two knees. The focus for the ACL-reconstructed knee is on swelling control and regaining ROM, while the focus for the contralateral knee is on controlled quadriceps muscle strengthening to rehabilitate the donor site.

The return-to-sport progression is based on the recovery of range of motion, swelling control, and strength rather than specific time frames. Once ROM is symmetric and swelling is under control, patients may begin doing light sports activities and individual drills involving such skills as ball handling and shooting. Patients are advanced into full practice and competitive situations once isokinetic quadriceps muscle strength is within 15% of the opposite knee. Our clinical experience has shown us that once athletes are permitted to return to full sports competition, it takes one to two months of participation at this level before they feel as if they have regained their full speed, agility, and confidence.

Summary

Ninety-five percent of competitive high school athletes were able to return to competitive athletics after ACL reconstruction, and 84% were able to return to the same sport at the same competitive level. There was no difference between boys and girls in the ability or time to return to competition after ACL reconstruction. For all sports, the mean time to return to light sports activities was 6.6 weeks, and the mean time to return to full competition was 5.4 months. The risk of re-injury to the ACL did not increase with early return to sports competition. Achieving and maintaining full range of motion after ACL reconstruction is the primary factor for obtaining a good long-term result.

Scott E. Urch, MD, is an orthopedic surgeon at the Shelbourne Knee Center in Indianapolis, IN, and an orthopedic consultant for Wabash College. K. Donald Shelbourne, MD is an orthopedic surgeon at the Shelbourne Knee Center and an orthopedic consultant for Purdue University. Heather Freeman, PT, DHS, is a physical therapist at the Shelbourne Knee Center.

References

1. Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Minimum 10-year results after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: How the loss of normal knee motion compounds other factors related to the development of osteoarthritis after surgery. Am J Sports Med 2009;37(3):471-480.

2. Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction based on the meniscal and articular cartilage status at the time of surgery: five- to fifteen-year evaluations. Am J Sports Med 2000;28(4):446-452.

3. Mastrokalos DS, Springer J, Siebold R, Paessler HH. Donor site morbidity and return to the preinjury activity level after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using ipsilateral and contralateral patellar tendon autograft: a retrospective, nonrandomized study. Am J Sports Med 2005;33(1):85-93.

4. Nakayama Y, Shirai Y, Narita T, et al. Knee functions and a return to sports activity in competitive athletes following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Nippon Med Sch 2000;67(3):172-176.

5. Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar tendon graft followed by accelerated rehabilitation. A two- to nine-year followup. Am J Sports Med 1997;25(6):786-795.

6. Shelbourne KD, Urch SE. Primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the contralateral autogenous patellar tendon. Am J Sports Med 2000;28(5):651-658.

7. Casteleyn PP. Management of anterior cruciate ligament lesions: surgical fashion, personal whim or scientific evidence? Study of medium- and long-term results. Acta Orthop Belg 1998;64(3):327-339.

8. Gobbi A, Diara A, Mahajan S, et al. Patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with conical press-fit femoral fixation: 5-year results in athletes population. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2002;10(2):73-79.

9. Keays SL, Bullock-Saxton JE, Keays AC, et al. A 6-year follow-up of the effect of graft site on strength, stability, range of motion, function, and joint degeneration after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: patellar tendon versus semitendinosus and gracilis tendon graft. Am J Sports Med 2007;35(5):729-739.

10. Kvist J, Ek A, Sporrstedt K, Good L. Fear of re-injury: a hindrance for returning to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2005;13(5):393-397.

11. Lee DY, Karim SA, Chang HC. Return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction — a review of patients with minimum 5-year follow-up. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2008;37(4):273-278.

12. Maletis GB, Cameron SL, Tengan JJ, Burchette RJ. A prospective randomized study of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a comparison of patellar tendon and quadruple-strand semitendinosus/gracilis tendons fixed with bioabsorbable interference screws. Am J Sports Med 2007;35(3):384-394.

13. Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with human allograft. Comparison of early and later results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78(4):524-537.

14. Pinczewski LA, Deehan DJ, Salmon LJ, et al. A five-year comparison of patellar tendon versus four-strand hamstring tendon autograft for arthroscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med 2002;30(4):523-536.

15. Seto JL, Orofino AS, Morrissey MC, et al. Assessment of quadriceps/hamstring strength, knee ligament stability, functional and sports activity levels five years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 1988;16(2):170-180.

16. Glasgow SG, Gabriel JP, Sapega AA, et al. The effect of early versus late return to vigorous activities on the outcome of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 1993;21(2):243-248.

17. Barber-Westin SD, Noyes FR, Andrews M. A rigorous comparison between the sexes of results and complications after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 1997;25(4):514-526.

18. Shelbourne KD, Sullivan AN, Bohard K, et al. Return to basketball and soccer after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in competitive school-aged athletes. Sports Health 2009;1(3):236-241.

19. National Collegiate Athletic Association. Estimated probability of competing in athletics beyond the high school interscholastic level. Accessed: 6/23/09.

20. Shelbourne KD, Gray T, Haro M. Incidence of subsequent injury to either knee within 5 years after ACL reconstruction with patellar tendon autograft. Am J Sports Med 2009;37(2):246-251.

21. Dienst M, Schneider G, Altmeyer K, et al. Correlation of intercondylar notch cross sections to the ACL size: a high-resolution MR tomographic in vivo analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007;127(4):253-260.

22. Davis TJ, Shelbourne KD, Klootwyk TE. Correlation of the intercondylar notch width of the femur to the width of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthosc 1999;7(4):209-214.

23. Staeubli HU, Adam O, Becker W, Burgkart R. Anterior cruciate ligament and intercondylar notch in the coronal oblique plane: anatomy complemented by magnetic resonance imaging in cruciate ligament-intact knees. Arthroscopy 1999;15(4):349-359.

24. Hewett TE. Neuromuscular and hormonal factors associated with knee injuries in female athletes. Strategies for intervention. Sports Med 2000;29(5):313-327.

25. Shelbourne KD, Wilckens JH, Mollabashy A, DeCarlo M. Arthrofibrosis in acute anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The effect of timing of reconstruction and rehabilitation. Am J Sports Med 1991;19(4):332-336.

Table 1. Mean time to return to low level sports activity and full competition based on sport.

Table 2. Subsequent ACL injuries to either knee based on gender.a

a From Shelbourne et al19

b n = 1415

c n = 863

d n = 552

I return to full contact varsity football playing tight-end 4 months after my ACL graft then got hit and tore it again now I don’t have insurance to get it fixed..