The etiology of Achilles tendon rupture is multifactorial, but the injury occurs most frequently in the athletic population. Clinicians still miss 24% of ruptures acutely, particularly in older patients, those in whom sports was not the causative mechanism, and those with high BMIs.

The etiology of Achilles tendon rupture is multifactorial, but the injury occurs most frequently in the athletic population. Clinicians still miss 24% of ruptures acutely, particularly in older patients, those in whom sports was not the causative mechanism, and those with high BMIs.

By Steven M. Raikin, MD

The Achilles tendon is a conjoined tendon, derived from the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, that inserts into the calcaneal tuberosity. It is the largest and strongest tendon in the human body and experiences the highest loads of any tendon in the body, with tensile loads reaching up to 10 times body weight during athletic activities.1 The tendon spirals about 90° from its origin to its insertion, and this twisting produces an area of stress approximately five to seven cm proximal to its insertion. There is a hypovascular watershed area at the same level, and the result is that this point is the most common location of Achilles tendon ruptures.2

The etiology of acute Achilles tendon ruptures is multifactorial and can include overuse injuries, host factors (e.g., biomechanical malalignment, hyperpronation, and cavus or varus foot), medications, or inappropriate footwear.3 In the recreational athlete acute Achilles tendon ruptures are predominately overuse injuries. Most of these are associated with midsubstance Achilles tendinopathy, which was seen histopathologically in the majority of ruptures in a 2003 study by Cetti et al.4

upture of the Achilles tendon is a common injury that causes significant morbidity. Research suggests that, over the past several decades, the incidence of rupture is increasing.5-7 Current estimates show an incidence of 2.66 ruptures per 1000 person-years,8,9 or about 18 ruptures (range 8.3-24) per 100,000 population.6,10-16

Epidemiology

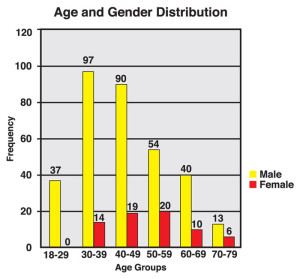

Figure 1: Graph illustrates distribution of Achilles ruptures by age and gender. Num- bers on top of columns correspond to the number of ruptures within each group.

Until recently, epidemiological studies on Achilles tendon ruptures have come from Europe,11,13,14,17 New Zealand,10,18 Canada,15 or military populations in the US.16,19 The largest demographic group in these studies were middle-aged men,20 and the injury was most frequently associated with athletic activity.17 In studies originating from Europe11,13,14 and Canada,15 soccer (called football in most published manuscripts out of Europe) was the most common sport involvement resulting in Achilles tendon ruptures. In two studies from New Zealand, however, netball (a basketball-like game played principally by female athletes) was by far the most common cause of ruptures.10,18 The only previous US studies were conducted with military personnel participants.16,19 These demonstrated that African American individuals in the military are at higher risk for rupturing tendons in general and including the Achilles tendon16,19 compared with their non-African American counterparts.21 Other reported risk factors include blood type O,22 antibacterial quinolone use,23 local corticosteroid injections,24 and anabolic steroid use.25

This author’s recent study on Achilles tendon demographics in the civilian US population retrospectively evaluated the demographics of 406 consecutive Achilles tendon ruptures.26 Consistent with prior publications, the majority of patients (83%) were men, but men were shown to be significantly younger (average 44.4 vs 50 years) than their female counterparts at the time of their Achilles tendon rupture. Twenty-six patients (6.4%) sustained nonconcurrent bilateral ruptures an average of 4.7 years apart. This suggests that, if one ruptures an Achilles tendon on one limb, the risk of a rupture on the contralateral side is significantly higher than that of the general population described above (6.4% compared with .018%).10,12,15 Twenty patients (4.9%) had previously ruptured the Achilles tendon in the same limb, and 85% (17 of 20) of these had the initial rupture treated with nonsurgical management. No side predominance was demonstrated, and there was no correlation between foot dominance and the side of injury.

We found ruptures occurred throughout the calendar year, but there was a significantly higher rate in the spring and summer months (March through August) than in the fall and winter months (September to February). The study was performed in the Northeastern US, where there is more outdoor sports participation during the spring and summer. March had the greatest number of Achilles tendon ruptures (46), while November and January had the fewest (24 each). No one season or month of the year had a significantly higher incidence than any other.

Figure 2: Pie chart illustrates the relative frequency of various injury mechanisms for Achilles tendon rupture, including sports injuries vs non-sports injuries.

The majority (68%) of ruptures occurred during sports participation. This was particularly true in patients younger than 55 years, in whom 77% of ruptures were sports related; by comparison, in those 55 years or older, 41% of ruptures were sports related. As expected based on clinical experience, but contrary to non-US published studies, basketball was the sport during which tendon rupture most commonly occurred, accounting for 47% of all sports-related ruptures (32% of all ruptures). This finding is due to the explosive eccentric forces applied on the Achilles tendon during the jumping, landing, and cutting activities associated with basketball. Additionally, it is not uncommon to find basketball players continuing to play the sport at some level into their middle to late 40s, the age at which ruptures most frequently occur.

Tennis was responsible for 13% of sports ruptures (9% of all ruptures), with American football causing 12% of sports ruptures (8% of all ruptures); racquetball and squash, 9% of sports ruptures (6% of all ruptures); volleyball, 4% of sports ruptures (3% of all ruptures); and soccer, 3% of sports ruptures (2% of all ruptures). Collectively, all other sports combined were responsible for causing the remaining 12% of sports ruptures.

One hundred thirty one patients (32%) were not involved in sports at the time of their ruptures. Thirty seven percent of these (12% of all ruptures) occurred while the patient was working, while the remaining (20% of all ruptures) mechanisms of injury typically involved normal daily activities such as walking, lifting objects, or tripping.

Figure 3: Pie chart illustrates the relative frequency with which different sports are associated with Achilles tendon rupture.

Ruptures were divided into “acute” (diagnosed within four weeks of injury) and “delayed” (diagnosed more than four weeks from injury). Among acute ruptures, 76% were appropriately diagnosed, but 96 patients were diagnosed at an average of 68 days (range, 28-240 days) after their injury. Missed or delayed diagnosis occurred more commonly in patients aged 55 years or older and the injury was more likely to result from an event not related to sports participation (34% vs 19% that occurred during sports).

Patients with delayed diagnosis of their ruptured Achilles tendon may continue to walk on their injured extremity, resulting in the gastroc-soleus muscles continuing to contract against the disrupted Achilles tendon. This will ultimately lead to gapping between the ends of the tendon and atrophy of the calf muscle. As the gapping distends beyond two centimeters, as is frequently seen after four weeks,31 nonoperative healing options are no longer viable and, if surgery is performed, more extensive operative procedures will be required to bridge the tendon gap. In addition to these procedures requiring more extensive and complex procedures, the outcomes of these salvage options, while functional, are not comparable to acute direct surgical repair or the results of immediate appropriate nonsurgical management.33-35

Our current study also analyzed the distribution of body mass index (BMI) as categorized by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the patients sustaining Achilles tendon ruptures.27-29 The average BMI was 28.8, but only 92 patients (23%) had a BMI that met the WHO definition of normal (BMI less than 25). In addition to being older and not participating in sports at the time of their rupture, patients in whom the diagnosis was delayed had a significantly higher average BMI of 32.3 compared with those in whom the diagnosis was made acutely. As expected, patients with a higher BMI were found to have a greater chance of rupturing their tendon in nonsporting-related activities than during sports participation.

Given that previous research had found African American race is a predisposing factor for Achilles tendon ruptures, this study also looked at race, but no clear relationship was demonstrated. Sixty three percent of patients in the study classified themselves as Caucasian; 31% as African American (43% of the regional population30); 2% as Hispanic; and 4% as Asian.

Other potential risk factors evaluated in the study included cigarette smoking (11%); preinjury use of quinolone antibiotics in the three months preceding rupture (2%); preinjury steroid injections into or around the Achilles tendon within six months of the rupture (3%); and comorbid diabetes (4%).

Although the studies mentioned above have increased understanding and awareness of predisposition to Achilles tendon rupture, there is scant evidence of specific ways to predict or prevent these injuries. Muscle tendon complex stiffness results in loss of elasticity and increased force transmission through the tendon during muscle firing. As such, tightness of the gastroc-soleus–Achilles complex (GSAC) has long been considered an associated risk factor for rupture, and stretching is anecdotally touted as a way of preventing these injuries. Experimental studies have demonstrated an increased dorsiflexion range of motion and decreased peak plantar flexion force through the GSAC following a pre-exercise stretching program.36,37 The authors contended this may reduce the risk of injury, but rupture was not the actual end point of the studies, and a study on military recruits did not find stiffness to be an intrinsic risk factor for injury.38 The most comprehensive literature review on the topic, published in 2006, concluded that few studies have been able to definitively demonstrate the utility of stretching exercises in Achilles injury prevention.39 That said, no disadvantage associated with stretching has been demonstrated, and it is still routinely recommended by orthopedic surgeons and sports medicine physicians in an attempt to prevent injury to the Achilles tendon.

Conclusion

The etiology of Achilles tendon ruptures is multifactorial, but the injury occurs most frequently in the athletic population. The male “weekend warrior”—the middle-aged man who participates in athletic endeavors only on an occasional basis—is at greatest risk of rupturing his Achilles tendon.5,8,11,12,13,15,19,26 Most Achilles tendon injuries, but not all, occur during sports participation, with basketball, tennis, and football being the activities most commonly associated with ruptures in the US, compared to soccer and volleyball in Europe11,13,14 and Canada15 and netball in New Zealand.10

Men are more likely than women to rupture their Achilles tendons and do so at a much younger age. Clinicians still miss 24% of ruptures acutely, particularly in older patients, those in whom sports involvement was not the causative mechanism, and those with high BMIs. With appropriate vigilance, the diagnosis can be made clinically without the need for tertiary studies such as MRI or ultrasound.31 Delay in making the diagnosis and initiating appropriate treatment can significantly affect outcome and increase morbidity associated with the injury.32-35 This further emphasizes the importance of a good physical exam, which should include a Thompson test, comparison of the resting tension of the ankle to the contralateral side, and palpation of the Achilles tendon for any gaps—the combination of which has been reported to have a 100% sensitivity in diagnosing acute Achilles ruptures.31

An Achilles tendon rupture in one limb increases the likelihood of a rupture on the contralateral side.32 It is important to inform the patient of this and emphasize the importance of preventive stretching exercises and activity modification to limit the risk of further

injury.

Steven M. Raikin, MD, is a professor of orthopaedic surgery at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, PA, and director of Foot and Ankle Services at the Rothman Institute in Philadelphia.

- Obrien M. The anatomy of the Achilles tendon. Foot Ankle Clin 2005;10(2):225-238.

- Chen TM, Rozen WM, Pan WR, et al. The arterial anatomy of the Achilles tendon: anatomical study and clinical implications. Clin Anat 2009;22(3):377-385.

- Kvist, M. Achilles tendon injuries in athletes. Ann Chir Gynaecol 1991;80(2):188-201.

- Cetti R, Junge J, Vyberg M. Spontaneous rupture of the Achilles tendon is preceded by widespread and bilateral tendon damage and ipsilateral inflammation: a clinical and histopathologic study of 60 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2003;74(1):78-84.

- Kvist M. Achilles tendon injuries in athletes. Sports Med 1994;18(3):173-201.

- Pajala A, Kangas J, Ohtonen P, Leppilahti J. Rerupture and deep infection following treatment of total Achilles tendon rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84(11):2016-2021.

- Selvanetti A, Cipolla M, Puddu G. Overuse tendon injuries: Basic science and classification. Oper Tech Sport Med 1997;5(3):110-117.

- Möller A, Astron M, Westlin N. Increasing incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop Scand 1996;67(5):479-481.

- Möller M, Movin T, Granhed H, et al. Acute rupture of tendon Achilles. A prospective randomized study of comparison between surgical and non-surgical treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83(6):843-848.

- Gwynne-Jones DP, Sims M, Handcock D. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute Achilles tendon rupture with operative or nonoperative treatment using an identical functional bracing protocol. Foot Ankle Int 2011;32(4):337-343.

- Houshian S, Tscherning T, Riegels-Nielsen P. The epidemiology of Achilles tendon rupture in a Danish county. Injury 1998;29(9):651-654.

- Leppilahti J, Puranen J, Orava S. Incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop Scand 1996;67(3):277-279.

- Maffulli N, Waterston SW, Squair J, et al. Changing incidence of Achilles tendon rupture in Scotland: a 15-year study. Clin J Sport Med 1999;9(3):157-160.

- Nyyssönen T, Lüthje P, Kröger H. The increasing incidence and difference in sex distribution of Achilles tendon rupture in Finland in 1987-1999. Scand J Surg 2008;97(3):272-275.

- Suchak AA, Bostick G, Reid D, et al. The incidence of Achilles tendon ruptures in Edmonton, Canada. Foot Ankle Int 2005;26(11):932-936.

- White DW, Wenke JC, Mosely DS, et al. Incidence of major tendon ruptures and anterior cruciate ligament tears in US Army soldiers. Am J Sports Med 2007;35(8):1308-1314.

- Krolo I, Visković K, Ikić D, et al. The risk of sports activities—the injuries of the Achilles tendon in sportsmen. Coll Antropol 2007;31(1):275-278.

- Flood L, Harrison JE. Epidemiology of basketball and netball injuries that resulted in hospital admission in Australia, 2000-2004. Med J Aust 2009;190(2):87-90.

- Davis JJ, Mason KT, Clark DA. Achilles tendon ruptures stratified by age, race, and cause of injury among active duty U.S. Military members. Mil Med 1999;164(12):872-873.

- Soldatis JJ, Goodfellow DB, Wilber JH. End-to-end operative repair of Achilles tendon rupture. Am J Sports Med 1997;25(1):90-95.

- Owens B, Mountcastle S, White D. Racial differences in tendon rupture incidence. Int J Sports Med 2007;28(7):617-620.

- Jozsa L, Balint JB, Kannus P, et al. Distribution of blood groups in patients with tendon rupture. An analysis of 832 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1989;71(2):272-274.

- van der Linden PD, Sturkenboom MC, Herings RM, et al. Increased risk of Achilles tendon rupture with quinolone antibacterial use, especially in elderly patients taking oral corticosteroids. Arch Intern Med 2003;163(15):1801-1807.

- Mahler F, Fritschy D. Partial and complete ruptures of the Achilles tendon and local corticosteroid injections. Br J Sports Med 1992;26(1):7-14.

- Inhofe PD, Grana WA, Egle D, et al. The effects of anabolic steroids on rat tendon. An ultrastructural, biomechanical, and biochemical analysis. Am J Sports Med 1995;23(2):227-232.

- Raikin SM, Garras DN, Krapchev PV. Achilles tendon injuries in a United States population. Foot Ankle Int 2013;34(4):475-480.

- Kuczmarski RJ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM, Troiano RP. Varying body mass index cutoff points to describe overweight prevalence among U.S. adults: NHANES III (1988 to 1994). Obes Res 1997;5(6):542-548.

- Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1995;854(i-xii):1-452.

- Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2000;894(i-xii):1-253.

- Census 2000 Gateway. United States Census Bureau website. http://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html. Accessed January 26, 2014.

- Garras DN, Raikin SM, Bhat SB, et al. MRI is unnecessary for diagnosing acute Achilles tendon ruptures: Clinical diagnostic criteria. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470(8):2268-2273.

- Arøen A, Helgø D, Granlund OG, Bahr R. Contralateral tendon rupture risk is increased in individuals with a previous Achilles tendon rupture. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2004;14(1):30-33.

- Maffulli N, Ajis A, Longo UG, Denaro V. Chronic rupture of tendo Achillis. Foot Ankle Clin 2007;12(4):583-596.

- Padanilam TG. Chronic Achilles tendon ruptures. Foot Ankle Clin 2009;14(4):711-728.

- Reddy SS, Pedowitz DI, Parekh SG, et al. Surgical treatment for chronic disease and disorders of the Achilles tendon. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2009;17(1):3-14.

- Rosenbaum D, Hennig EM. The influence of stretching and warm-up exercises on Achilles tendon reflex activity. J Sports Sci 1995;13(6):481-490.

- Fowles JR, Sale DG, MacDougall JD. Reduced strength after passive stretch of the human plantarflexors. J Appl Physiol 2000;89(3):1179-1188.

- Mahieu NN, Witvrouw E, Stevens V, et al. Intrinsic risk factors for the development of Achilles tendon overuse injury: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2006;34(2):226-235.

- Park DY, Chou L. Stretching for prevention of Achilles tendon injuries: a review of the literature. Foot Ankle Int 2006;27(12):1086-1095.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks