Shutterstock.com #31101100

Evidence from the medical literature suggests that calf muscle stretching, whether manually or with the aid of a brace or splint, can help alleviate plantar fasciitis pain. What’s less clear, however, is which specific stretching method and protocol is most effective.

by Neena K Sharma, PT, PhD, CMPT, and Gurpreet Singh, PT

Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of heel pain,1-3,11 accounting for 10% to 15% of all foot conditions.1 Plantar fasciitis results from degenerative inflammation of the plantar fascia. The injury is caused by shortening of the plantar fascia, which causes chronic bone traction in the heel and formation of bone spurs.4,16 Recent studies estimated that plantar fasciitis affects two million people in the United States1,5-7 and accounts for one million visits to physicians and other health care professionals.2,8-12 While plantar fasciitis is frequently reported in athletic populations1,2,13,14 and in people engaged in standing jobs, the condition has been reported in sedentary populations as well.10,13,15,16 In more than 80% of patients, symptoms resolve within eight to 12 months with some form of conservative therapy;1,5,6,8,11,16-18 however, approximately 10% of cases progress to chronic heel pain.5,6,9,13

The wide range of etiologies of plantar fasciitis includes aberrant foot biomechanics, foot overpronation, shortening of the Achilles tendon, shortening of the calf muscles (gastrocnemius and soleus), pes cavus, decreased ankle and 1st metatarsophalangeal joint range of motion, leg length discrepancy, lateral tibial torsion, femoral anteversion, and improper footwear.8,11 A thorough evaluation should be performed to address the underlying associated findings.

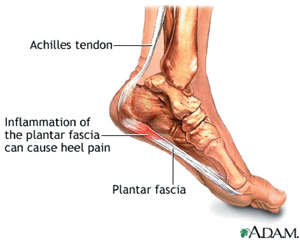

Plantar fasciitis is often associated with decreased great toe extension and ankle dorsiflexion range of motion. The plantar fascia originates from the medial tubercle of the calcaneus and inserts into the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe distally (Figure 1). Great toe extension during the push off phase of the gait cycle winds the fascia around the metatarsal head. This winding causes shortening of the fascia, through what is known as the windlass mechanism, which is important to create foot rigidity and facilitate gait propulsion.19,20 In addition, the calf muscle-tendon unit is very important for walking and running. Approximately 10° of ankle range of motion is required for normal walking. The shortening of the calf muscles limits ankle dorsiflexion, which is an important etiological factor in plantar fasciitis.21 Limited dorsiflexion due to shortened calf muscles, a shortened Achilles tendon, or decreased ankle joint motion cause greater compensatory pronation, increasing the risk of inflammation of the plantar fascia. Therefore, Achilles tendon and plantar fascia stretching programs are commonly employed to increase the range of motion and decrease pressure on the inflamed plantar fascia. In addition, foot orthoses are prescribed to provide optimal load distribution and foot alignment by supporting the arch and for pain relief.2,4,22-24

Conservative management

Figure 1. Plantar Fascia

Diagnosis of plantar fasciitis is based on clinical signs and symptoms. Patients with plantar fasciitis experience mild to severe pain on the plantar aspect of the foot, which limits their ability to walk and participate in recreational activities. Specifically, the pain is worse during the first few steps in morning.9,25,26 The pain is aggravated by weight bearing and worsens towards the end of the day and with prolonged standing. Other neuromusculoskeletal conditions of the lower extremities may mimic symptoms of plantar fasciitis related heel pain, including lumbar spine disorders, neuropathies, Tarsel Tunnel syndrome, fat pad atrophy, heel contusion, plantar fascia rupture or reterocalcaneal bursitis etc.16,27 However, plantar fasciitis is recognized by localized pain at the center or the medial aspect of the heel or the arch of the foot.

Several conservative treatment strategies are known to improve symptoms of the condition, including electrical modalities, soft tissue massage, acupuncture, night splints, orthotics, shoe inserts, stretching, ice, heat, strengthening, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, and corticosteroids.1,6,10-13,25 Almost all the above-mentioned forms of therapy provide relief of symptoms. However there is no consensus on what is the best treatment option for plantar fasciitis. Stretching has been identified as one of the best, safe and cost effective conservative therapy for plantar fasciitis.5,13,25,26-28 For this review, we will focus on the evidence related to stretching and the effects of stretching on the tightened fascia, specifically related to the use of braces for stretching.

The purpose of stretching is to relieve stress on the tightened fascia and tendon and to restore the normal range of motion of the ankle and the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint. The rationale is that when stretching is applied to a tissue, the tissue responds through either the elastic (temporary lengthened state) or plastic (permanent lengthened state) changes.39 To effectively treat the shortened plantar fascia, the goal of the stretching program is to reach the plastic deformation state. Studies have indicated the effectiveness of various stretching programs with documented decrease in pain on first steps in the morning, and relief of other symptoms associated with plantar fasciitis.5,13,20,28-30

Static progressive stretch brace

We have recently tested the efficacy of a relatively new day wear brace, a static progressive stretch (SPS) brace (Figure 2) in a small group of patients with chronic plantar fasciitis (mean duration 12.2 years).6 The brace is designed to allow passive stretch of the Achilles and plantar fascia. The brace works on the principle of stress relaxation to achieve elongation and plastic deformation of the shortened structures, similar to the concept utilized in serial casting.31,32 Since plastic deformation is a desirable outcome for shortened soft tissues, it is believed that this type of stretching would be helpful in treating plantar fasciitis. Patients gradually manipulate a knob on the brace to adjust the level of stretch to elongate tissues as they relax, maximizing the viscoelastic nature of the soft tissue. Tissues are held at a constant length in individual’s pain free range over a period of time, which causes tissues to relax and elongate in a fixed position.30 As tissues relax, further stretch is applied within the pain free range, gaining further range of motion beyond the toe region of the stress/strain curve. The cycle of stretch and relax is continued for a 30-minute session, three times a day33,34 for eight weeks. Further details are available in the original article.6

Figure 2. Static Progressive Stretch Brace

The SPS orthosis has been used to improve joint range of motion in other conditions such as elbow contractures,33,34 wrist stiffness,35 arthrofibrosis of knee, and total knee replacement surgeries.36,37 It offers the option of stretching both tissues, the Achilles tendon by dorsiflexion of the ankle and the plantar fascia by extending the great toe, either separately or simultaneously. In our study,6 17 subjects were randomly assigned to either the SPS ankle brace group or a manual stretching exercise group. Subjects in the brace group used the SPS brace three times a day, 30 minutes at a time, for eight weeks. Subjects in the manual stretching group performed plantar fascia massage and manual stretches of the plantar fascia, gastrocnemius and soleus in weight bearing and non-weight bearing positions, three times a day for eight weeks; each stretch was held for 30 seconds for a total of six minutes of stretching every day. Both groups were given prefabricated foot orthotics, as a standard treatment of arch support.22,23,30

The stretching protocol for SPS brace implemented in our study, which was based on previous studies using the SPS brace,4 seemed to have worked well for the study population with plantar fasciitis. Both groups experienced a statistically significant (p = .005) decrease in pain and improvement in functional limitations, with the SPS group showing a slightly greater but nonsignificant improvement at the three-month follow up visit. There was a 30% dropout rate in the SPS group and approximately 10% in the manual stretching exercise group. Those who completed the study reported the brace to be a useful option. No negative effects were noted in subjects using the SPS brace. Our study results support the use of SPS brace for people with plantar fasciitis. However, the utility and efficacy of the SPS brace should be assessed in a larger trial, which will assist clinicians in considering its possible use for individual patients.

Night splint

Another brace option, the night splint, has long been used to treat plantar fasciitis. Several studies38-40 have investigated the effectiveness of the posterior dorsiflexion splint/night splint for the treatment of plantar fasciitis; however most of these studies have yielded mixed reviews. The purpose of the splints is to keep the ankle in neutral position mostly during the night. Night splints differ from the SPS brace in that they are designed to place constant load on the tissues for an extended period of time using the creep concept.41 Splints worn at night keep the foot either in a neutral position or in 5º of dorsiflexion, which prevents chronic shortening of the fascia or the posterior leg muscles. Although the splints are frequently used for treatment of plantar fasciitis, most of the studies had high dropout rates and low compliance, possibly due to discomfort caused by the splint. Further, the literature is lacking evidence of superior benefits of the night splint compared to other conventional treatment measures.

In a recent study, Beyzadeoglu et al38 studied 44 patients with plantar fasciitis symptoms averaging 7.2 ± 5.9 weeks in duration. The authors reported greater short term improvement in pain and function in subjects who agreed to wear a night splint in conjunction with standard conservative treatment of a silicone heel cushion, oral NSAIDs, stretching, exercise, and diet recommendation for overweight individuals, compared to the group who did not use the night splint. However, a high percentage (63%) of the patients reported some form of difficulty with the splint. The splint was designed to maintain 5° of dorsiflexion and was worn for eight weeks. No significant improvement relative to baseline was noted at two-year follow up, and both groups showed significant recurrence rates (p=0.05) of plantar fasciitis. The authors concluded that the night splint use for eight weeks combined with other conservative methods can be beneficial in patients receiving first time treatment and presenting with a short duration of symptoms. Others have also reported early use of the night splint as a beneficial option for plantar fasciitis with respect to reduced recovery time and fewer follow up visits.40,42

In another retrospective study, Barry et al39 compared the effects of adding prefabricated night splints to standing gastrocnemius stretching in patients with plantar fasciitis. Out of 160 patients, 71 patients used a standing stretching technique for the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, and 89 patients used standing stretching and prefabricated night splints. The authors observed that the night splint group had significantly shorter recovery time; fewer follow up visits, and fewer additional interventions. Similar to Beyzadeoglu’s study, the results of this study support the early use of night splint.

In contrast, Probe et al40 studied night splinting for three months duration in addition to other conservative treatments. Two groups of subjects with plantar fasciitis received one month of anti-inflammatory medication, Achilles tendon stretching and shoe modification. In addition, one of the two groups used a night splint for three months. Almost 68% of patients reported improvement in symptoms at four-, six-, and 12-week and nine-month follow up; however, no significant differences were observed between the two groups. Finally, Martin et al42 compared the efficacy of night splints to that of over-the-counter and custom-made orthotics and reported no difference between groups for pain and function at three months. They reported poor compliance with night splint and better compliance with custom made orthotics.

Manual/active stretches

Manual passive stretching/active stretching of the Achilles tendon and plantar fascia are the mainstay treatment for plantar fasciitis. Several studies have tested the efficacy of manual stretches with positive results.5,13,25,28,30 A classic study conducted by Pfeffer et al30 with 236 subjects provided some of the earliest evidence that Achilles and plantar fascia stretches in combination with prefabricated orthosis comprise a beneficial conservative treatment. In a recent multisite, randomized control trial, Cleland et al25 demonstrated significant improvement on the Lower Extremity Functional Scale, the Foot and Ankle Ability Measure, and the Numeric Pain Rating Scale at four-week and six-month follow up, with aggressive soft tissue mobilization of the triceps surae and insertion of the plantar fascia, along with stretching exercises. Greve et al28 also assessed the effectiveness of combined treatments, including stretching exercises and ultrasound or radial shockwave therapy. Their results suggested that combined treatment of ultrasound and stretching of gastrocnemius and plantar fascia being are as effective as radial shockwave therapy and stretching of the gastrocnemius and plantar fascia. In another study, Hyland et al1 reported a decrease in pain with plantar fascia stretching and calcaneal taping.

Although it is known that stretching of plantar fascia and stretching of the calf muscles result in improvements in subjects with plantar fasciitis, limited data exist about the superiority of one type of stretching over the other. Further, clinical guidance to employ one stretching over the other is unclear or not well defined. In a randomized controlled trial, DiGiovanni et al13 compared the efficacy of plantar fascia stretching versus Achilles tendon stretching in a sample of 101 subjects with symptom duration greater than 10 months. In addition to the assigned stretches, all subjects received over the counter prefabricated insoles, three weeks of celecoxib, and a patient educational video. Plantar fascia stretches were performed while sitting and the Achilles tendon while standing by one group, three times a day, for 10 repetitions with a hold of 10 seconds per repetition. At the end of eight weeks, both groups reported significant improvement on the Foot Function Index, but those in the plantar fascia stretching group had significantly greater improvement with respect to worst pain and pain with first steps in the morning. The plantar fascia stretching group also had a higher percentage of positive responses to an outcomes survey in terms of pain, activity and satisfaction. After eight weeks, patients from both groups were instructed to continue with plantar fascia stretching. At two-year follow up,5 both groups continued to show improvement on the pain subscales of the FFI compared to baseline. However, no group differences were observed. These two studies suggest that plantar fascia stretches provide better symptom relief for chronic plantar fasciitis.

In a prospective randomized controlled trial, Porter et al29 randomized 94 subjects to either sustained stretching or intermittent stretching of the Achilles tendon. The sustained stretching group was instructed to stretch for three minutes, three times a day; the intermittent group was instructed to perform five 20-second stretches twice a day. After four months, the authors noticed improved dorsiflexion range of motion, pain, and foot and ankle function in both the groups compared to baseline, but no significant group differences were observed, indicating that greater length of stretch did not provide greater benefits. Increased dorsiflexion range of motion correlated with decreased pain and increased function for both groups. There was no long term follow up and a high dropout rate (29.8%) was observed.

Radford et al12 randomized 92 participants with plantar heel pain into two groups, one receiving calf stretches and sham ultrasound and the control group receiving sham ultrasound only. A wooden wedge was placed under the forefoot for standing stretches, five minutes a day, either in small sessions totaling five minutes or a continuous five-minute stretch. At the end of two weeks, both groups reported decreased pain in the first step, foot pain, foot function and general foot health. However, there were no statistically significant differences between groups. These results are in contrast with the previous studies which demonstrated improvement with calf stretching.13,28-30

Conclusions

In summary, we found that the majority of the stretching protocols, either manual self stretching or braces (night splints or SPS devices), help in alleviating the symptoms of plantar fasciitis pain and foot dysfunction. In spite of the fact that a lack of group differences were observed in some cases, most of the studies found some improvement in dorsiflexion range of motion, pain on the first step in the morning, and foot function. We also believe that results of our study as well as other similar studies favor the use of stretching as the main treatment strategy for plantar fasciitis; however, a combination of stretching with other forms of conservative treatment seems to be a better treatment option. The literature also suggests that symptom improvement can be achieved with various stretching methods and protocols, whether active or passive, intermittent for five to 30 minutes or sustained for 5 minutes, when practiced for at least eight weeks. Manual stretches are usually performed three times a day, each stretch held for 30 seconds, at least five days over eight weeks.6,13,29

After reviewing the literature, it is still difficult to predict the best stretching method and protocol that is most helpful in reducing the pain and increasing function in patients with plantar fasciitis, leaving clinicians with a lack of specific guidelines. However, it can be concluded from these studies that the Achilles tendon stretch is more beneficial for plantar fasciitis of short duration,13 and there is some evidence for use of the night splint in plantar fasciitis of short duration.39,40 Further, plantar fascia stretches seem to be more effective in chronic cases of plantar fasciitis.30 Our pilot study also supports the use of the SAS brace for treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis,6 although further studies are needed to confirm this finding. For patients who have had difficulties with the use of night splints, a day-wear SAS brace could be another possible option. In addition to the phase of healing, patient’s work environment, lifestyle, and the costs associated with treatment should be considered when prescribing a treatment regimen. The patient’s compliance with the suggested treatment method should also be monitored and alternative options should be provided.

Neena K. Sharma, PT, PhD, CMPT, is a research assistant professor and an associate academic coordinator of clinical education with the Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation science at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, KS. Gurpreet Singh, PT, is a graduate student in the rehabilitation science program at the same university. He is conducting his dissertation work with Dr. Sharma.

References:

1. Hyland MR, Webber-Gaffney A, Cohen L, Lichtman PT. Randomized controlled trial of calcaneal taping, sham taping, and plantar fascia stretching for the short-term management of plantar heel pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2006;36(6):364-371.

2. Landorf KB, Keenan AM, Herbert RD. Effectiveness of foot orthoses to treat plantar fasciitis: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(12):1305-1310.

3. Donley BG, Moore T, Sferra J, et al. The efficacy of oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication (NSAID) in the treatment of plantar fasciitis: a randomized, prospective, placebo-controlled study. Foot Ankle Int 2007;28(1):20-23.

4. Stuber K, Kristmanson K. Conservative therapy for plantar fasciitis: a narrative review of randomized controlled trials. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2006;50(2):118-133.

5. Digiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Malay DP, et al. Plantar fascia-specific stretching exercise improves outcomes in patients with chronic plantar fasciitis. A prospective clinical trial with two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88(8):1775-1781.

6. Sharma NK, Loudon JK. Static progressive stretch brace as a treatment of pain and functional limitations associated with plantar fasciitis: a pilot study. Foot Ankle Spec 2010;3(3):117-124.

7. Roxas M. Plantar fasciitis: diagnosis and therapeutic considerations. Altern Med Rev 2005;10(2):83-93.

8. Lohrer H, Nauck T, Dorn-lange NV, et al. Comparison of radial versus focused extracorporeal shock waves in plantar fasciitis using functional measures. Foot Ankle Int 2010;31(1):1-9.

9. Kudo P, Dainty K, Clarfield M, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial evaluating the treatment of plantar fasciitis with an extracoporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT) device: a North American confirmatory study. J Orthop Res 2006;24(2):115-123.

10. Radford JA, Landorf KB, Buchbinder R, Cook C. Effectiveness of low-Dye taping for the short-term treatment of plantar heel pain: a randomised trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2006;7:64.

11. Yucel I, Yazici B, Degirmenci E, et al. Comparison of ultrasound-, palpation-, and scintigraphy-guided steroid injections in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009;129(5):695-701.

12. Radford JA, Landorf KB, Buchbinder R, Cook C. Effectiveness of calf muscle stretching for the short-term treatment of plantar heel pain: a randomised trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2007;8:36.

13. DiGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Lintal ME, et al. Tissue-specific plantar fascia-stretching exercise enhances outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85(7):1270-1277.

14. Dogramaci Y, Kalaci A, Emir A, et al. Intracorporeal pneumatic shock application for the treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis: a randomized, double blind prospective clinical trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010;130(4):541-546.

15. Riddle DL, Pulisic M, Pidcoe P, Johnson RE. Risk factors for plantar fasciitis: a matched case-control study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85(5):872-877.

16. Cole C, Seto C, Gazewood J. Plantar fasciitis: evidence-based review of diagnosis and therapy. Am Fam Physician 2005;72(11):2237-2242.

17. Baldassin V, Gomes CR, Beraldo PS. Effectiveness of prefabricated and customized foot orthoses made from low-cost foam for noncomplicated plantar fasciitis: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009;90(4):701-706.

18. League AC. Current concepts review: plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int 2008;29(3):358-366.

19. Caravaggi P, Pataky T, Goulermas JY, et al. A dynamic model of the windlass mechanism of the foot: evidence for early stance phase preloading of the plantar aponeurosis. J Exp Biol 2009;212(Pt 15):2491-2499.

20. Bolgla LA, Malone TR. Plantar fasciitis and the windlass mechanism: a biomechanical link to clinical practice. J Athl Train 2004;39(1):77-82.

21. Gajdosik RL, Vander Linden DW, McNair PJ, et al. Effects of an eight-week stretching program on the passive-elastic properties and function of the calf muscles of older women. Clin Biomech 2005;20(9):973-983.

22. Gross MT, Byers JM, Krafft JL, et al. The impact of custom semirigid foot orthotics on pain and

disability for individuals with plantar fasciitis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2002;32(4):149-157.

23. Roos E, Engstrom M, Soderberg B. Foot orthoses for the treatment of plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int

2006;27(8):606-611.

24. Hume P, Hopkins W, Rome K, et al. Effectiveness of foot orthoses for treatment and prevention of lower limb injuries: a review. Sports Med 2008;38(9):759-779

25. Cleland JA, Abbott JH, Kidd MO, et al. Manual physical therapy and exercise versus electrophysical agents and exercise in the management of plantar heel pain: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2009;39(8):573-585.

26. Young CC, Rutherford DS, Niedfeldt MW. Treatment of plantar fasciitis. Am Fam Physician 2001;63(3):467-474.

27. Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Canoso JJ. Heel pain: diagnosis and treatment, step by step. Cleve Clin J Med 2006;73(5):465-471.

28. Greve JM, Grecco MV, Santos-Silva PR. Comparison of radial shockwaves and conventional physiotherapy for treating plantar fasciitis. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2009;64(2):97-103.

29. Porter D, Barrill E, Oneacre K, May BD. The effects of duration and frequency of Achilles tendon stretching on dorsiflexion and outcome in painful heel syndrome: a randomized, blinded, control study. Foot Ankle Int 2002;23(7):619-624.

30. Pfeffer G, Bacchetti P, Deland J, et al. Comaprison of custom and prefabricated orthosis in the initial treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int 1999;20(4):214-221.

31. Rose KJ, Raymond J, Refshauge K, et al. Serial night casting increases ankle dorsiflexion range in children and young adults with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: a randomised trial. J Physiother 2010;56(2):113-119.

32. Ho ES, Roy T, Stephens D, Clarke HM. Serial casting and splinting of elbow contractures in children with obstetric brachial plexus palsy. J Hand Surg Am 2010;35(1):84-91.

33. Bonutti PM, Windau JE, Ables BA, Miller BG. Static progressive stretch to reestablish elbow range of motion.

Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994;(303):128-134.

34. Hotz MW. Clinical management of soft tissue stiffness and loss of joint motion. Inside Case Manag 2001;8:11-12.

35. McGrath MS, Ulrich SD, Bonutti PM, et al. Evaluation of static progressive stretch for the treatment of wrist stiffness. J Hand Surg 2008;33(9):1498-1504.

36. Bonutti PM, Marulanda GA, McGrath MS, et al. Static progressive stretch improves range of motion in arthrofibrosis following total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2010;18(2):194-199.

37. Bonutti PM, McGrath MS, Ulrich SD, et al. Static progressive stretch for the treatment of knee stiffness. Knee 2008;15(4):272-278.

38. Beyzadeoglu T, Gokce A, Bekler H. [The effectiveness of dorsiflexion night splint added to conservative treatment for plantar fasciitis]. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2007;41(3):220-224.

39. Barry LD, Barry AN, Chen Y. A retrospective study of standing gastrocnemius-soleus stretching versus night splinting in the treatment of plantar fasciitis. J Foot Ankle Surg 2002;41(4):221-227.

40. Probe RA, Baca M, Adams R, Preece C. Night splint treatment for plantar fasciitis. A prospective randomized study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999(368):190-195.

41. Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: Foundations and technique. 4TH ed. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis; 2002.

42. Martin JE, Hosch JC, Goforth WP, et al. Mechanical treatment of plantar fasciitis. A prospective study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2001;91(2):55-62.

“The injury (plantar fasciitis) is caused by shortening of the plantar fascia”, was stated in the article. What is the proposed etiology responsible for the shortening?

It is my understanding that Davis’ Law of Soft Tissue would account for shortening of both the plantar fascia and Achilles tendon. We spend at least 1/3 of the day non-weight bearing with our ankles plantar flexed as we sleep.