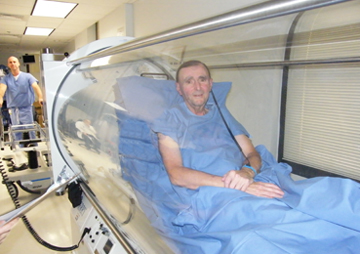

Photo courtesy of MedStar Georgetown University Hospital.

Two February publications sum up the polarizing nature of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) for treating recalcitrant diabetic foot ulcers. A meta-analysis supported use of HBOT, while a large cohort study found a lack of effectiveness in community-care settings.

By Larry Hand

Just as boxers have to show their mettle every time they get into the ring, advocates of hyperbaric oxygen therapy as an adjunctive therapy for treating recalcitrant diabetic foot ulcers are constantly under pressure to prove the technology’s worth. Commonly described as being founded on limited clinical evidence, the field nevertheless is moving forward—at least for some patients.

A systematic review and meta-analysis and a longitudinal observational cohort study, published separately within weeks of each other last month, demonstrate the push and pull among researchers and practitioners with regard to the relative effectiveness of HBOT.

The systematic review/meta-analysis, published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings,1 was the first of the two to be published. It concluded that HBOT improves healing rates of foot ulcers and reduces lower extremity amputations in diabetic patients, compared with no HBOT, and can be used to improve patient quality of life. But the authors of the observational study published in Diabetes Care2—the largest HBOT study to date—concluded that HBOT neither improved ulcer healing nor reduced amputations compared with no HBOT in community-based wound care centers.

“We’re slowly trying to put the science behind hyperbaric oxygen and its effects, in terms of what is it that is hastening healing in some patients [while] other patients are healing poorly,” said Stephen R. Thom, MD, MPH, chief of hyperbaric medicine at the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute for Environmental Medicine and professor of emergency medicine at Children’s Hospital, Philadelphia, and a coauthor of the Diabetes Care paper. “On a practical level, we still have a ways to go for better identification of patients for whom hyperbaric oxygen therapy might be more appropriate.”

In the Mayo Clinic Proceedings paper, researchers analyzed the results of 13 clinical trials (out of 89 relevant trials) published between 1966 and April 20, 2012. The number of patients totaled 624. This included randomized and nonrandomized trials comparing HBOT as an adjunct to conventional therapy versus conventional therapy alone in patients with chronic diabetic foot ulcers. Conventional therapy included glycemic control, revascularization, debridement, off-loading, and metabolic and infection control.

Photo courtesy of MedStar Georgetown University Hospital.

In a pooled analysis, the researchers found that adjunctive HBOT resulted in a significantly higher rate of healed ulcers (relative risk 2.33, 1.51-3.60) than no HBOT and a significant reduction in risk of major amputations (relative risk .29, .19-.44), but did not affect minor amputations. They found that adverse events were rare and reversible and comparable to those associated with no HBOT treatment.

The researchers included in their analysis human trials published in full text in any language that were randomized and controlled or unrandomized but either crossover or parallel-designed or prospective or retrospective; included diabetes types 1 and 2 patients with lower extremity ulcers whose diabetes was treated with conventional therapy as described above; compared HBOT plus conventional therapy with therapy and no HBOT; and reported proportion of healed ulcers, amputations, and other factors.

In the Diabetes Care article, researchers analyzed the records of 6259 patients treated for foot ulcers at 83 National Healing Corporation (NHC) wound care management clinics in 31 states between November 2005 and May 2011. In propensity score-adjusted models, patients who received HBOT were less likely to have healed ulcers (hazard ratio .68, .63-.73) and more likely to have an amputation (hazard ratio 2.37, 1.84-3.04).

A total of 11,301 patients with 32,021 wounds were enrolled at the centers during that time. The 6259 patients in the analysis included only patients whose ulcers did not heal or decrease in size by at least 40% during the first 28 days of regular care. HBOT was given to 12.7% of those patients, usually at 2 atmospheres, five days a week, in 90-minute sessions.

Hundreds of programs around the country offer wound care services, including HBOT, Thom said.

“Most people will get standard care, and many will have surgery. Is there a more or less appropriate time during treatment where hyperbaric oxygen is used? How many times is hyperbaric oxygen used before we say it’s not really going to help? This all requires more study,” he said.

The process and recent history

During HBOT, an adjunctive therapy used with traditional wound care treatment, patients are placed in a hyperbaric chamber and exposed to 100% oxygen at two to three times greater pressure than ambient atmosphere. Protocols can vary, but an exposure of 2.4 atmospheres for 90 minutes is appropriate for most indications, said Roy Monsour, MD, interim director of hyperbaric medicine at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, DC. For diabetic foot ulcers, most patients get 30 to 35 treatments at a once-a-day pace (weekdays), but for some patients 80 treatments are administered.

The history of HBOT has been plagued by lesser-quality clinical trials, said Andrew Boulton, MD, DSc, professor of medicine at the University of Manchester, UK, and visiting professor at the University of Miami in Florida.

“The problem has been insufficient randomization. They haven’t had a proper control group that was blinded. There was mismatch in many of the studies in severity across groups. And trials have not been necessarily blinded,” explained Boulton, who has not referred patients to HBOT.

But results published in 2010 provided some hope that HBOT might be useful, Boulton said. Published in Diabetes Care,3 the Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in Diabetics with Chronic Foot Ulcers (HODFU) study was a randomized double-blinded trial in which patients received either hyperbaric oxygen or hyperbaric air (placebo) through an HBOT treatment protocol. After one year, ulcer healing was achieved in 37 of 90 patients, 25 of 48 (52%) in the HBOT group and 12 of 42 (29%) in the placebo group. Of patients completing more than 35 hyperbaric sessions, ulcer healing was achieved in 23 of 38 (61%) patients in the HBOT group and 10 of 37 (27%) patients in the placebo group.

“That study was properly conducted, although it’s interesting to note that there was no benefit statistically until nine months after the treatment started,” Boulton said. “The [HODFU] study was the only really high-quality study, and that gave us some optimism for patients with diffuse distal disease or chronic infection. If they have chronic neuroischemic foot ulcers, there may be a place for [HBOT].”

An editorial in the same issue of Diabetes Care4 stated, “The study …, standing on the shoulders of previous trials, has placed HBOT on firmer ground.” Key issues that remain include development of criteria to determine which patients are apt to benefit, at what point HBOT should be started or stopped, and which protocols are most appropriate, according to the editorial.

“It’s very difficult to run a clinical trial on hyperbaric oxygen,” said John Steinberg, DPM, an associate professor in the Department of Plastic Surgery at the Georgetown University School of Medicine. “The peer-review literature level of evidence remains low and is limited to a few key studies. Because of that people can easily view it with skepticism. We do have four hyperbaric chambers and we are very selective in how we prescribe the therapy.”

He added, “Hyperbarics is and can be a very powerful limb salvage tool, but it requires proper patient selection. It is most effective for failed flaps, or for acute arterial insufficiency, or gangrene, to help in healing or to define that border between healthy and unhealthy tissue to help facilitate surgery. For osteomyelitis, I believe its use should be limited to a combination with surgery only. We know a lot about oxygen wound healing, but each clinical scenario is different. Patient selection is key.”

Monsour, who runs Georgetown’s hyperbaric center, said guidelines were originally developed by the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society, then adopted in large part by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), as well as some insurance companies. (The newly published Diabetes Care study used CMS guidelines as a reference.) He said common guidelines included:

- The wound has failed to heal after 30 days of standard wound care (but standard care is not defined)

- The foot is maximally revascularized

- The patient’s diabetes is under control

- Lab evaluations show the patient has adequate nutrition

- “Basically everything has been tried and there’s still no healing.”

- Ulcers should be at least Wagner grade 3 (a deep ulcer with abscess or osteomyelitis)

Patients, patients, patients

That last point is why some of the clinical trials have been looked upon with skepticism, said David Armstrong, DPM, MD, PhD, professor of surgery and director of the Southern Arizona Limb Salvage Alliance (SALSA) at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson. Although Wagner grade 3 indicates more severe ulcers, some studies have included patients with lesser Wagner grade ulcers.

“These [the severest cases] are not the patients that have been studied well in the current clinical studies that concentrated on people without severe disease,” Armstrong said. “That is not to say that [HBOT] doesn’t help people and not to say it doesn’t have a place. It’s complicated because of the history, and companies that are tied inexorably to hyperbarics that are developing wound-healing centers around the country and around the world.”

There is still some holdover in the healthcare arena from many years ago when hyperbarics was dismissed as quackery, said Armstrong, who refers patients to HBOT only when a patient is recalcitrant to other methods of treatment and he believes the patient will “respond to an oxygen challenge.” SALSA does not have its own hyperbaric chambers, however.

“I think it will become less and less controversial,” Armstrong continued. “Whether it will be more widely used, I don’t know. We need more evaluation on sicker patients.”

How does it work?

A few mechanisms have been suggested, but the verdict is still out on the exact mechanism of HBOT.

Thom described potential mechanisms in a 2011 paper published in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.5 It appears to work through a combination of systemic and local alterations within the wound margin, he wrote, as HBOT affects both angiogenesis, which can stimulate development and differentiation of circulating stem/progenitor cells and result in vasculogenesis.

“So far that looks the most attractive,” Thom told LER. “It’s also quite obvious there’s not a single mechanism. It’s probably a combination of many different things occurring essentially at the same time. Hyperbaric oxygen stimulates synthesis of quite a number of different growth factors. Changing the view of the wound site itself doesn’t necessarily have to be the stem cell story. We know that diabetics don’t mobilize stem cells nearly as well as nondiabetics. There may be nonresponders. We’re still trying to tease out those clinical variables, and there’s obviously a lot of work to be done.”

Steinberg is an advocate of the theory that, in wounds with adequate perfusion, HBOT may overcome periwound hypoxia to create an oxygen gradient and stimulate healing of otherwise nonhealing wounds.6,7

“If a patient has good blood flow, we might be able to maximize that blood flow at the wound through hyperbarics, but hyperbarics cannot be a replacement for revascularization,” Steinberg said.

Why some patients and not others?

The magnitude of vascular injury is the key, Thom said.

“If a patient has a large femoral artery occlusion from atherosclerosis, they need a vascular surgeon. If they don’t have a reasonable degree of blood flow to the extremity, all the hyperbaric oxygen in the world isn’t going to heal an ulcer,” he said.

In the 2010 Diabetes Care editorial,4 the authors wrote: “It seems clear that in a center of excellence of both HBOT and diabetic foot care, like the one [where the 2010 study was conducted], HBOT can help heal refractory wounds. It is unnecessary for the great majority of patients, however, who will respond to appropriate wound care.”

Monsour thinks that HBOT is just going through the learning stages that all new technologies go through: “Derision, hostile resistance, then generalized acceptance. For the most part, we’re between resistance and acceptance right now.”

Few practitioners are exposed to hyperbarics during training, he said, and it’s not something they think of right away.

“When you’re in an area for a period of time, gradually you start getting referrals because a wound won’t heal. We become the route of last resort, and as some of those patients have success, we get thought of earlier. For instance, for radiation cystitis and proctitis, we have a really good record of curing and nobody else really does,” he said.

Even in the most recent Diabetes Care paper2 that failed to find HBOT benefits in the community healthcare environment, the authors posited that perhaps the goal post should be moved for HBOT.

“HBO has the potential to have many differing effects on a chronic wound and it may not be reasonable to assume that this therapy should be used to fully heal a wound,” they wrote. “In fact, those who study wound care have been concerned that the requirement by regulators that a wound care product must heal a wound to receive approval may be naïve and not consistent with the biology of wound repair. HBO therapy may have a beneficial effect on microbial balance, soft tissue infection, and angiogenesis. HBO simply may be a part of the answer and not a therapy that should be used until a wound fully heals.”

For practitioners, Thom said, sorting out the ins and outs of HBOT is a very important focus.

“If you say, ‘hyperbaric oxygen is good,’ someone will ask, ‘how does it work?’ We can’t in a very few words tell people how it works,” he said. “We need more people doing more work.”

Larry Hand is a writer in Massachusetts.

1. Liu R, Li L, Yang M, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygenation therapy in the management of chronic diabetic foot ulcers. Mayo Clin Proc 2013;88(2):166-175.

2. Margolis DJ, Gupta J, Hoffstad O, et al. Lack of effectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer and the prevention of amputation. A cohort study. Diabetes Care 2013 Feb 19. [Epub ahead of print]

3. Londahl M, Katz P, Nilsson A, Hammarlund C. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy facilitates healing of chronic foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33(5):998-1003.

4. Lipsky, BA, Berendt AR. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for diabetic foot wounds. Diabetes Care 2010;33(5):1143-1145.

5. Thom SR. Hyperbaric oxygen: its mechanisms and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127(Suppl 1):131S-141S.

6. Daly MC, Faul J, Steinberg JS. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy as an adjunctive treatment for diabetic foot wounds: A comprehensive review with case series. Wounds 2010;22(1):1-11.

7. Knighton DR, Silver IA, Hunt TK. Regulation of wound-healing angiogenesis—effect of oxygen gradients and inspired oxygen concentration. Surgery 1981;90(2):262-270.