By David P. Taormina, MD, and Nirmal C. Tejwani, MD

By David P. Taormina, MD, and Nirmal C. Tejwani, MD

Early mobilization and weight bearing after Achilles tendon repair is associated with improved patient satisfaction and faster return to work and sports, with no significant increase in rates of tendon rerupture or postoperative wound and nerve complications.

Achilles tendon pathology can present at any age, but epidemiologic studies have shown that men aged between 30 and 50 years are at greatest risk.1 The annual incidence of Achilles tendon rupture is approximately one in 5000 and has increased in recent decades.2-4 While there are well known risk factors, including the use of certain antibiotics (fluoroquinolones5) and steroid injections,6 the classic history that precedes rupture is that of the episodic athlete—the “weekend warrior.”7

When the injury is the result of sports activity, research has shown that the sport being played at the time of injury varies by geodemographic distribution. In the US, those afflicted are more likely to have been injured while playing basketball, tennis, or football,7 whereas Europeans are more likely to suffer an Achilles injury playing soccer or volleyball.1,2,8 In most of these instances, the deconditioned athlete attempts to perform and exercise at or near their previous level of activity without accounting for the consequential deterioration of connective tissues associated with aging and physical quiescence.

With hyperacute tensile stress across the Achilles tendon, albeit volitional or associated with trauma, sudden plantar flexion or the violent dorsiflexion of a plantar flexed foot forces the largest tendon in the body9 to the brink of failure. The tendinous bridge between the gastrocnemius-soleus complex (GSC) and the calcaneus is at greatest risk for failure at the hypovascular region found approximately four to six centimeters proximal to its calcaneal insertion.10

The resultant “pop,” which is so often reported by patients, results in the sudden onset of pain, weakness, and difficulty with ambulation. Upon examination in the emergency setting or the physician’s office, a lack of plantar flexion force and unopposed dorsiflexion of the anterior leg musculature, become a primary finding on inspection, especially when the patient is lying prone. Confirmation can be made with palpation of a gap between the GSC and heel along with weakness or inability to stand on one leg. The Thompson test,11 a failure of foot plantar flexion with a squeeze of the calf, further confirms the diagnosis. In the rare situation that diagnostic imaging is required,12 magnetic resonance imaging is the modality of choice.

Operative vs nonoperative management

The war of operative versus nonoperative management for Achilles tendon ruptures has been waged for well over 30 years.13,14 The debate is fueled on one side by the advantages of surgery for decreasing risk for rerupture and quickening time to return to activity and work. On the other side of the debate, proponents of nonoperative management cite risks of scar adhesion, postoperative paresthesias, and skin sensitivity, and potential sequelae of superficial infections. In fact, these were the study conclusions from a recent meta-analysis by Jiang and colleagues published in 2012.15 Despite an extensive investment of research time and a tome-sized plethora of publications, this well-powered review of 10 randomized clinical trials, which included nearly 900 patients, found insufficient evidence to support either operative or nonoperative management.

The war of operative versus nonoperative management for Achilles tendon ruptures has been waged for well over 30 years.13,14 The debate is fueled on one side by the advantages of surgery for decreasing risk for rerupture and quickening time to return to activity and work. On the other side of the debate, proponents of nonoperative management cite risks of scar adhesion, postoperative paresthesias, and skin sensitivity, and potential sequelae of superficial infections. In fact, these were the study conclusions from a recent meta-analysis by Jiang and colleagues published in 2012.15 Despite an extensive investment of research time and a tome-sized plethora of publications, this well-powered review of 10 randomized clinical trials, which included nearly 900 patients, found insufficient evidence to support either operative or nonoperative management.

While the embers continue to burn from a smoldering debate between a prosurgery school of thought and proponents of nonoperative management of Achilles rupture in the general population, a number of studies have recommended that elite athletes and high functioning individuals undergo percutaneous or open surgical repair for a ruptured Achilles tendon.16-22 The principal surgical methods described in the literature are percutaneous repair23,24 through multiple portal incisions, a minimally invasive posterolateral approach25 using a two- to six-cm incision, and the standard open six- to 18-cm posteromedial approach.23

Postoperative rehabilitation

While the literature is rife with publications describing modifications to the documented surgical techniques, this volume of surgical literature is still eclipsed by the number of postoperative protocol descriptions. Given the debate being resolved between operative versus nonoperative management, it would be ideal to have a postoperative plan that maximizes functional recovery and soft tissue healing while minimizing morbidity, including pain, Achilles rerupture, and associated prolonged hospital course.

The theoretical advantages of early mobilization after Achilles surgery include hastened return of tensile strength to the repaired tendon. There is, however, also a risk for increased rupture end gapping, rerupture, or both. In addition, another proposed advantage is that early motion prevents formation of adhesions that may ultimately block final range of motion.26

Several studies have described the outcomes of patients who were made nonweight-bearing for six weeks after surgery.27 In fact, a meta-analysis performed by Suchak and colleagues included six randomized trials that compared patients made partial weight bearing on postoperative day one versus patients with conversion to weight bearing at three, four, and six weeks postoperatively.27-32 Focusing on rates of Achilles rerupture, subjective patient satisfaction, range of motion (ROM), strength, wound infections, and other minor postoperative complications, their meta-analysis compared a cohort of 315 patients treated with early mobilization (n = 159) versus late weight bearing (n = 156) after operative repair of Achilles tendon rupture.

Ultimately, early functional treatment protocols were associated with patients who were subjectively more satisfied (88% rated postoperative satisfaction as excellent vs adequate or poor) than delayed mobilizers (62% rated satisfaction as excellent, p < .0001). There was no statistically significant difference between the rates of Achilles rerupture, which occurred in 2.5% of the early function group and in 3.8% of the immobilized patients (p = .47). These rates nearly mirrored the incisional infection rates, as well, which were 2.6% in early mobilizers versus 3.9% in the latent mobilizers (p = .63). Finally, analysis of an amalgamated variable for other postoperative complications (including sural nerve injury) found that early weight bearing was actually associated with significantly lower complication rates than immobilization (5.8% vs 13.5%, p = .01).27

Studies documenting strength and range of motion after early versus delayed rehabilitation have been less than convincing with regard to recommendations for optimizing patient outcomes. Meta-analysis of available data has shown that early functional protocols were associated with improved calf tone and plantar flexion in one study, but these findings failed to find support in the majority of available literature.27 Similarly, advantages in range of motion for early rehabilitation have been supported, at best, inconsistently in the literature.27

Using an animal model (rats), one study has shown that early physical activity increases the speed of tissue healing after acute Achilles rupture.33 Bring and colleagues used histochemical staining to first identify the postoperative period of peak tissue and nerve regeneration, which occurs between weeks two and four. Using this information, they then chose the four-week time point to compare three groups of rats that were treated with different postoperative physical activity protocols: wheel running, plaster treatment, and a control group (no strict physical activity protocol). They found that the wheel-running group did best, showing 94% greater (p = .001) and 48% greater (p = .02) diameter of newly organized collagen than plaster-treated and control rat groups, respectively. Histologic staining demonstrated the wheel-running group also had signs of earlier neuronal ingrowth.

A study by our group compared the outcomes of 63 consecutive patients who presented with acute closed Achilles tendon ruptures, 62 of whom had a minimum of six months follow-up after being treated with either minimally invasive open or standard open surgical repair for an acute Achilles tendon rupture.19

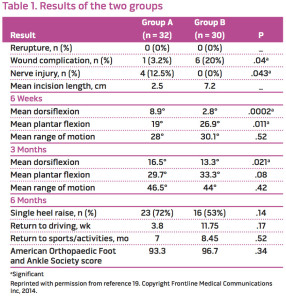

After surgery, the patient was immobilized in a 10° to 20° equinus splint (minimally invasive group) or removable boot with a 30° heel wedge (standard group) for two weeks. All patients (33 treated minimally invasively, 30 treated with standard open procedure) were then encouraged to begin weight bearing at two weeks postoperatively, as tolerated, with a controlled ankle movement boot fitted with a 20° heel wedge. We theorized that postoperative rehabilitation should be delayed approximately two weeks to allow for the start of early tendinous fibrous union and to stabilize the soft tissues of the ankle in the postoperative period while incisional wound healing occurred. At six weeks postoperatively, all patients were converted to a regular shoe with a heel lift. Range of motion, surgical complications (including rerupture and poor wound healing), and sural nerve injury, were assessed postoperatively at the six-week, three-month, and six-month (with GSC strength assessment) time points. The findings are summarized in Table 1.

There were no reruptures identified throughout the postoperative course of the 63 patients. Superficial infections were more prevalent in the standard open group (six patients, 20%) than in the minimally invasive group (one patient, 3%, p = .04). All soft tissue issues resolved without requiring return to the operative suite. Sural nerve deficits were documented in four patients (12.5%) in the minimally invasively treated patients versus none in the standard open group (p = .04). Three of these four nerve deficits resolved by the six-month follow-up visit, which raises the suspicion that they were sequelae of traction.

Functional outcomes at final follow-up in 62 patients, using the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society Scores, did not differ significantly between the groups. Patients had similar arcs of motion during their postoperative course (28° vs 30.1° at six weeks, p = .52) though the minimally invasive group had greater dorsiflexion (8.9° versus 2.8°, p < .01) while the standard open group had greater plantar flexion (26.9° vs 19°, p = .01); this may have been because the well-molded posterior plaster splints positioned the foot in 30° of equinus (for the open group) versus 10° of equinus (for the minimally invasive surgical group).

Regarding postoperative strength and conditioning, at six-month follow-up, we found that 23 patients (72%) in the minimally invasive group were able to perform a single heel raise (five of the nine who failed to perform heel raise had 4+/5 GSC strength), versus 16 of the 30 standard open patients (53%; eight of 14 who failed conditioning testing had 4+/5 GSC strength). Although the data trended toward better results with minimally invasive treatment, the differences were not statistically significant (p = .14).

The findings of our group continue to support the existing literature on the early rehabilitation of patients after surgical repair of Achilles tendon rupture.34-38 In fact, each of the studies we reviewed identified advantages of early postoperative mobilization and weight bearing with, at worst, equivocal complication rates. Furthermore, earlier mobilization was also associated in one study (Suchak et al34) with a quicker return to sports activity and a reduction in the number of lost workdays.

Although within our study we employed a two-week postoperative initiation protocol for the commencement of weight-bearing rehabilitation, there are other studies promoting partial weightbearing exercises as early as postoperative day one.23 We are unable to document the necessity of a two-week postoperative rehabilitation holiday using scientifically objective findings, but we do subjectively believe there may be a role for an early postoperative hiatus in order for early tendinous healing to begin bridging the Achilles rupture gap and for the early progression of the soft tissue healing process.

Conclusion

The available literature supports, unequivocally, early mobilization and weight bearing in patients after surgical repair of Achilles tendon rupture. Studies have found that early rehabilitation is associated with improved early range of motion. During the early postoperative course, rehabilitation has been shown to improve patient’s subjective ratings of satisfaction, expedite return to work, and allow quicker return to sports activity. When comparing patients with early mobilization to those immobilized four to eight weeks postoperatively, there are no differences in Achilles tendon rerupture rates, and similar, or slightly improved, rates of postoperative wound and nerve complications.

David Taormina, MD, is an orthopedic surgery resident at the NYU Langone Medical Center, Hospital for Joint Diseases, in New York City. Nirmal Tejwani,MD, is a trauma fellowship trained surgeon and professor of orthopaedic surgery at NYU Langone Medical Center, Hospital for Joint Diseases, and at the Bellevue Hospital Medical Center in New York City.

- Houshian S, Tscherning T, Riegels-Nielsen P. The epidemiology of Achilles tendon rupture in a Danish county. Injury 1998;29(9):651-654.

- Nyyssonen T, Luthje P, Kroger H. The increasing incidence and difference in sex distribution of Achilles tendon rupture in Finland in 1987-1999. Scand J Surg 2008;97(3):272-275.

- Bhandari M, Guyatt GH, Siddiqui F, et al. Treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: a systematic overview and metaanalysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002(400):190-200.

- Leppilahti J, Puranen J, Orava S. Incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop Scand 1996;67(3):277-279.

- Huston KA. Achilles tendinitis and tendon rupture due to fluoroquinolone antibiotics. N Engl J Med 1994;331(11):748.

- Kleinman M, Gross AE. Achilles tendon rupture following steroid injection. Report of three cases. J Bone J Surg 1983;65(9):1345-1347.

- Raikin SM, Garras DN, Krapchev PV. Achilles tendon injuries in a United States population. Foot Ankle Int 2013;34(4):475-480.

- Maffulli N, Waterston SW, Squair J, et al. Changing incidence of Achilles tendon rupture in Scotland: a 15-year study. Clin J Sport Med 1999;9(3):157-160.

- Fornage BD. Achilles tendon: US examination. Radiology 1986;159(3):759-764.

- Jones DC. Tendon disorders of the foot and ankle. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1993;1(2):87-94.

- Thompson TC. A test for rupture of the tendo achillis. Acta Orthop Scand 1962;32:461-465.

- Garras DN, Raikin SM, Bhat SB, e al. MRI is unnecessary for diagnosing acute Achilles tendon ruptures: clinical diagnostic criteria. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2012;470(8):2268-2273.

- Edna T-H. Non-operative treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures. Acta Orthop Scand 1980;51(6):991-993.

- Wilkins R, Bisson LJ. Operative versus nonoperative management of acute Achilles tendon ruptures a quantitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med 2012;40(9):2154-2160.

- Jiang N, Wang B, Chen A, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for acute Achilles tendon rupture: a meta-analysis based on current evidence. Int Orthop 2012;36(4):765-773.

- Bradley JP, Tibone JE. Percutaneous and open surgical repairs of Achilles tendon ruptures. A comparative study. Am Journal Sports Med 1990;18(2):188-195.

- Karabinas PK, Benetos IS, Lampropoulou-Adamidou K, et al. Percutaneous versus open repair of acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2014;24(4):607-613.

- Maffulli N, Longo UG, Maffulli GD, et al. Achilles tendon ruptures in elite athletes. Foot Ankle Int 2011;32(1):9-15.

- Tejwani NC, Lee J, Weatherall J, Sherman O. Acute achilles tendon ruptures: a comparison of minimally invasive and open approach repairs followed by early rehabilitation. Am J Orthop 2014;43(10):E221-E225.

- Khan RJ, Carey Smith RL. Surgical interventions for treating acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010(9):CD003674.

- Strauss EJ, Ishak C, Jazrawi L, et al. Operative treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: an institutional review of clinical outcomes. Injury 2007;38(7):832-838.

- Nistor L. Surgical and non-surgical treatment of Achilles tendon rupture. A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg 1981;63(3):394-399.

- Gigante A, Moschini A, Verdenelli A, et al. Open versus percutaneous repair in the treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture: a randomized prospective study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008;16(2):204-209.

- Ma GW, Griffith TG. Percutaneous repair of acute closed ruptured achilles tendon: a new technique. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1977(128):247-255.

- Rippstein PF, Jung M, Assal M. Surgical repair of acute Achilles tendon rupture using a “mini-open” technique. Foot Ankle Clin 2002;7(3):611-619.

- Mortensen NHM, Skov O, Jensen PE. Early motion of the ankle after operative treatment of a rupture of the Achilles tendon. A prospective, randomized clinical and radiographic study. J Bone Joint Surg 1999;81(7):983-990.

- Suchak AA, Spooner C, Reid DC, Jomha NM. Postoperative rehabilitation protocols for Achilles tendon ruptures: a meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2006;445:216-221.

- Maffulli N, Tallon C, Wong J, L et al. Early weightbearing and ankle mobilization after open repair of acute midsubstance tears of the achilles tendon. Am J Sports Med 2003;31(5):692-700.

- Maffulli N, Tallon C, Wong J, et al. No adverse effect of early weight bearing following open repair of acute tears of the Achilles tendon. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2003;43(3):367-379.

- Cetti R, Henriksen LO, Jacobsen KS. A new treatment of ruptured Achilles tendons. A prospective randomized study. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1994(308):155-165.

- Costa ML, Shepstone L, Darrah C, et al. Immediate full-weight-bearing mobilisation for repaired Achilles tendon ruptures: a pilot study. Injury 2003;34(11):874-876.

- Kangas J, Pajala A, Siira P, et al. Early functional treatment versus early immobilization in tension of the musculotendinous unit after Achilles rupture repair: a prospective, randomized, clinical study. J Trauma 2003;54(6):1171-1180.

- Bring DK, Kreicbergs A, Renstrom PA, Ackermann PW. Physical activity modulates nerve plasticity and stimulates repair after Achilles tendon rupture. J Orthop Res 2007;25(2):164-172.

- Suchak AA, Bostick GP, Beaupre LA, et al. The influence of early weight-bearing compared with non-weight-bearing after surgical repair of the Achilles tendon. J Bone Joint Surg 2008;90(9):1876-1883.

- Majewski M, Schaeren S, Kohlhaas U, Ochsner PE. Postoperative rehabilitation after percutaneous Achilles tendon repair: early functional therapy versus cast immobilization. Disabil Rehabil 2008;30(20-22):1726-1732.

- Ozkaya U, Parmaksizoglu AS, Kabukcuoglu Y, et al. Open minimally invasive Achilles tendon repair with early rehabilitation: functional results of 25 consecutive patients. Injury 2009;40(6):669-672.

- Twaddle BC, Poon P. Early motion for Achilles tendon ruptures: is surgery important? A randomized, prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2007;35(12):2033-2038.

- Calder JD, Saxby TS. Early, active rehabilitation following mini-open repair of Achilles tendon rupture: a prospective study. Br J Sports Med 2005;39(11):857-859.

I had an Accidental injury to left tendo achilis and avulsion fracture of left calcaneum on 28.07.2019 followed by surgical repair of tendo achilis and application of pop cast on 29.07.2019. My pop cast is removed on yesterday and now I am feeling stiffness around left ankle. Please, comment.